Jaguar: The Glamour, the Glitches, the Legend

Most car companies build perfectly rational machines. They are bought and sold on the strength of their practicality, their boot space, and their ability to get from one place to another with the least possible fuss. Their owners are sensible people who make sensible choices.

Jaguar, however, was built for those who prefer passion to reason. These are individuals who operate on a different, altogether more romantic frequency. They accept a certain amount of character in exchange for owning something truly beautiful. For a century, this company has catered to that specific, glorious madness: the belief that a perfect curve is worth any amount of trouble. To own a Jaguar is to understand that beauty comes with consequences. The oil stains on the driveway and the recovery vehicle are part of the package.

The Blackpool Philosophy

The company began in 1922 in Blackpool, a seaside resort built on a particular principle: give people more than they expect for what they pay. Millions of visitors a year descended on Blackpool for glamour and entertainment they could actually afford. The entire town was dedicated to making working people feel like aristocrats for a week.

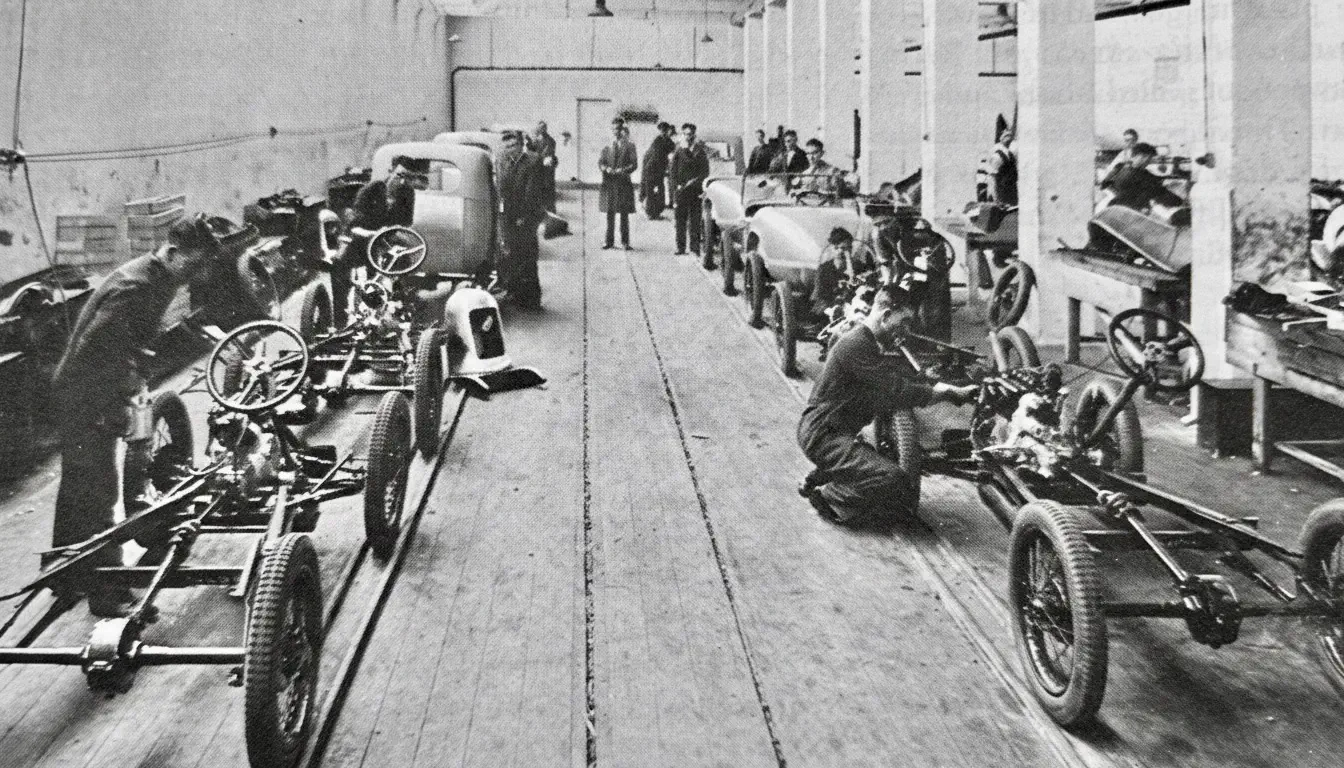

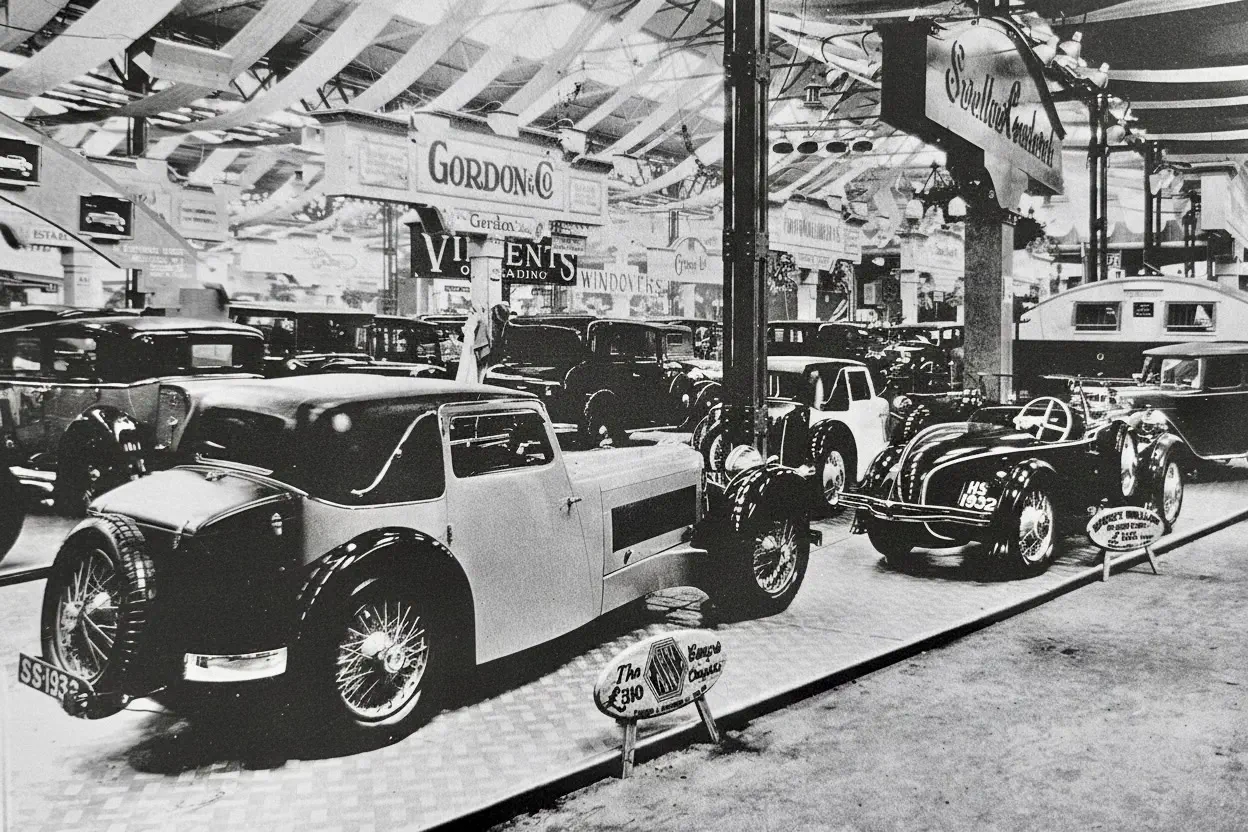

William Lyons understood this instinctively. He and his partner, William Walmsley, began by building motorcycle sidecars, then moved on to rebodying cheap Austin and Standard chassis in the late 1920s. By the 1930s, they had perfected the formula: take something affordable and make it look like a million pounds. The mechanicals were humble; the styling was not. This was Blackpool applied to motorcars. You couldn’t afford a Bentley, but you could afford something that looked as if it should cost as much as one. The gap between perception and price was where Jaguar lived.

When William Heynes joined in 1935 and gave the cars proper performance to match their looks, the formula became irresistible. The SS Jaguar 100 genuinely did 100 mph and looked like it cost twice what it did. Beautiful, fast, and affordable. This was not just clever marketing. This was a business model that would sustain the company for a century.

The Post-War Statement

In 1948, Britain was grey, rationed, and exhausted. Lyons unveiled the XK120 at Earls Court: impossibly low, impossibly sleek, impossibly fast. The styling was so shocking that people assumed it must be foreign. The 120-mph top speed sounded less like a specification and more like a threat. The company was buried in orders from people who apparently craved threats.

When Heynes convinced Lyons that racing would be useful, Jaguar won Le Mans in 1951 with the C-Type, then again in 1953 with disc brakes whilst everyone else's drums cooked into uselessness. Malcolm Sayer's mathematically-designed D-Type won three consecutive years. The message was clear: Jaguar's beauty had substance.

The Defining Moment

The E-Type of 1961 was the car that defined what Jaguar meant. Long, low, indecently gorgeous, and offering 150-mph performance for £2,000. Enzo Ferrari called it the most beautiful car ever made, which was generous considering it was faster than most Ferraris and cost less than half as much. An Aston Martin DB4 cost £4,000. A Ferrari 250 GT cost even more. The E-Type looked like it belonged in that company but was priced for doctors, successful barristers, and newly famous footballers rather than hereditary wealth.

Here was the Blackpool philosophy perfected: democratised glamour. Not just for the old money who could afford Aston Martins, but for anyone who had arrived in the new 1960s and wanted the world to know it. The E-Type was a social marker that announced you valued style over sensibility, passion over prudence, and you had excellent taste but not unlimited funds. You were the sort of person who would sacrifice reliability for beauty and call it a fair trade. This attracted a very specific type of customer and repelled another type entirely, which was rather the point.

The saloons told the same story. The Mark 2 was bought by bank managers and bank robbers, both groups appreciating the combination of elegance and speed. The XJ6 of 1968 was so refined that German rivals looked agricultural by comparison. It featured two fuel tanks with separate filler caps, one in each rear wing. Symmetrical, impractical, beautiful. This could serve as Jaguar's engineering philosophy: solve problems nobody else has, then make the solution lovely.

The Long Decline

When Lyons retired in 1972 and merged Jaguar into British Leyland, the company entered its wilderness years. Starved of investment, assembled by a workforce in open revolt against management, Jaguars of the 1970s and 1980s were gorgeous cars that frequently did not work. The XJS replaced the E-Type in 1975 with a heavy body wrapped around a magnificent V12. The XJ40 of 1986 looked modern and broke creatively.

Yet people kept buying them. This is the remarkable thing. Faced with overwhelming evidence that their Jaguar would spend significant time being repaired, customers bought them anyway. The styling was too seductive. The alternative was a BMW that worked perfectly but looked like it had been designed by someone who viewed beauty as frivolous. For a certain type of person, this was not actually a choice. You bought the Jaguar and developed a relationship with your local garage. This was understood.

The Ford Era and the Perception Problem

Ford bought Jaguar in 1989 and brought quality control. The cars started working reliably, which was novel. The XK8 of 1996 was elegant and dependable, maintaining the Blackpool principle: it looked more expensive than it was and actually worked.

Then Ford made the catastrophic error of pursuing volume. The X-Type of 2001 was a Ford Mondeo with a Jaguar badge, wrong proportions from front-wheel-drive origins, built for people who wanted the status without the sacrifice. But here was the real problem: it looked cheap. The styling was anonymous. The proportions were wrong. The Blackpool principle collapsed entirely. The car neither looked expensive nor was it particularly affordable. It was just a Mondeo in a suit, and everyone could tell.

The X-Type destroyed the perception equation. For decades, Jaguars had looked like they cost more than they did. The X-Type looked exactly like what it cost, possibly less. When people stopped believing a Jaguar looked special, they stopped buying them. The financial losses were severe but the reputational damage was worse. Jaguar had forgotten that looking expensive was more important than actually being expensive. The subsequent XE and XF saloons were competent but anonymous, continuing the perception problem. They looked like every other executive saloon, which meant they looked like nothing special at all.

The Tata Renaissance

When Tata Motors bought Jaguar in 2008, they understood something Ford had not: Jaguar worked precisely because it was not trying to be BMW. The investment was substantial and patient. The F-Type of 2013 was a proper sports car that made antisocial noises. The F-Pace SUV handled like a sports car that happened to be tall. The I-Pace proved electric power could have character.

Under Tata, Jaguar stopped apologising for what it was. The cars were beautiful, characterful, and occasionally impractical. They were for people who valued how a car made them feel over how it performed in Consumer Reports. Sales improved because Jaguar had rediscovered its purpose.

The Pink Jaguar Gamble

Then, in 2024, Jaguar announced it was scrapping everything. The entire range disappeared: F-Type, F-Pace, XE, XF, all gone. The plan was to reinvent the company as an ultra-luxury, all-electric rival to Bentley and Rolls-Royce, with prices starting around £250,000. The relaunch came with a fashion-show aesthetic, pink cars in the publicity shots, and marketing that suggested Jaguar was now for people who wear interesting clothes to gallery openings rather than for people who enjoy driving.

Existing customers were baffled. The wider public was bemused. Social media reacted with the cruelty reserved for brands that appear to have lost their minds. Jaguar replied that it no longer cared about its old buyers. The company wanted a new clientele, the very wealthy who preferred silent cars with presence.

That decision broke both parts of the Jaguar formula. First, the cars would no longer look as if they cost more than they did; they would cost more than most houses, abandoning the Blackpool principle of accessible glamour. Second, they would be quiet, sensible electric vehicles built for people who treat cars as accessories rather than experiences. The passion, the character, and the touch of impracticality that once defined Jaguar vanished in pursuit of a market already owned by Bentley and Rolls-Royce.

Whether that audience exists in numbers large enough to sustain a manufacturer remains to be seen. Early signs do not inspire confidence, but the strategy could still succeed. There may be enough buyers who crave silent, high-prestige electric cars with Jaguar badges. The cars might be superb. The engineering might surprise everyone. The new direction could yet mark the moment Jaguar reinvented itself for a new century.

Or it could mark the moment Jaguar forgot that beauty has consequences, that character matters more than fashion, and that a brand built on passion cannot suddenly cater to people who see cars as accessories.

One thing is certain: Jaguar has never known how to play it safe. The recovery truck is no longer part of the package. Whether that counts as progress is something Jaguar will discover soon enough.