The Fathers Who Bet the House on Motorcycle Furniture

Thomas Walmsley made his money from coal. Lots of it, hauled in wagons from Reddish Station across industrial Cheshire, where everything looked grey because everything was grey. By 1921 he had accumulated enough to retire, and chose Blackpool. What he could not have anticipated was that his choice of retirement address would accidentally create Jaguar.

The mechanism was simple enough. Blackpool put his war-wounded son, William, within motorcycle distance of an ambitious twenty-year-old salesman named William Lyons, son of an Irish piano dealer. Two Williams, two fathers, and a small brick shed where sidecars were built one per week while someone's wife did the upholstery. Then both fathers signed a bank guarantee for £1,000, which in 1922 would have bought a rather nice house, with enough left over to buy another one. During deflation. Four years before the General Strike. For motorcycle furniture.

The Sergeant with the Aluminium Habit

William Walmsley joined the Cheshire Yeomanry in 1911 and served through the war in Egypt, Palestine, and France, where he earned sergeant's stripes and a bullet in his right leg. He came home in 1918 with a limp, a decoration or two, and absolutely no desire to spend his life moving coal like his father. The conventional path of inheriting the family business held no appeal for a man who had spent six years in considerably worse conditions than a coal yard.

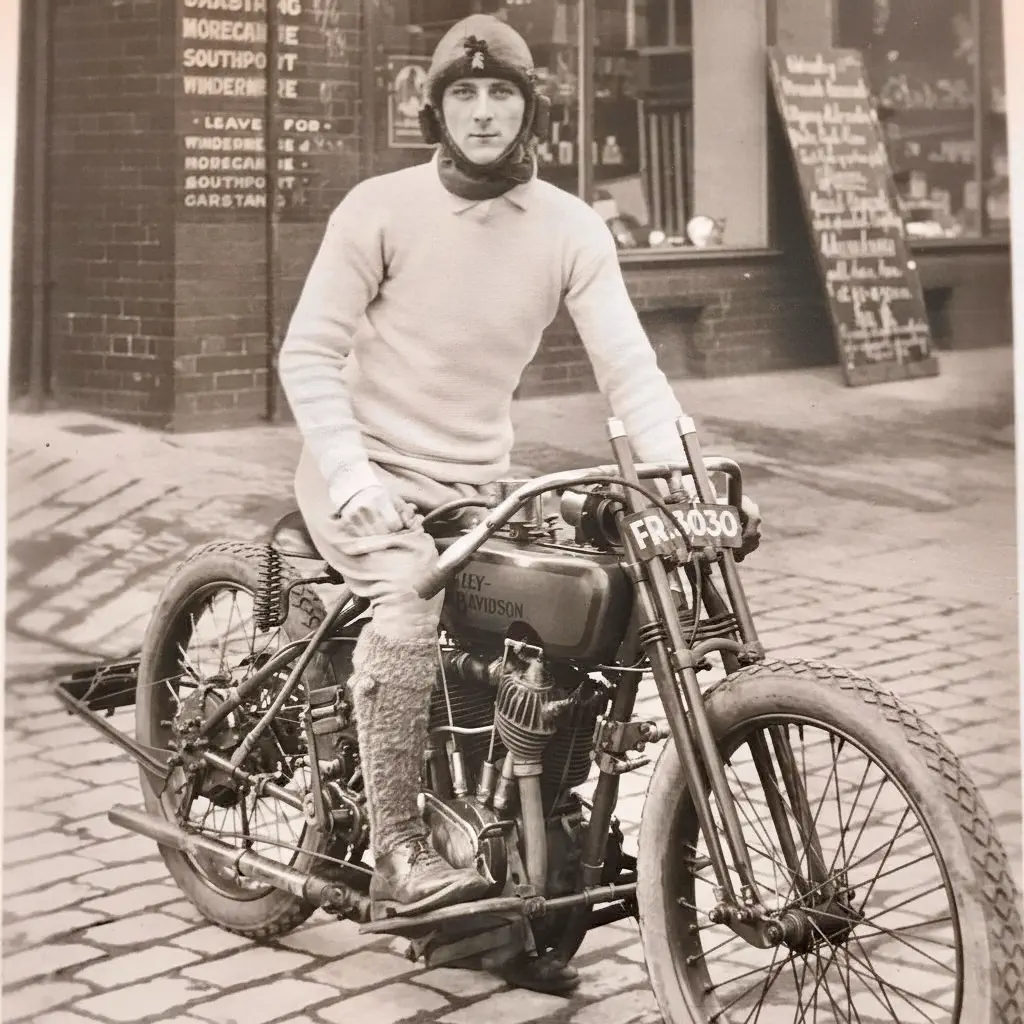

He acquired a surplus War Department Triumph and spent his time rebuilding it in the summerhouse at the bottom of the garden. Other ex-servicemen noticed. The business of war always leaves surplus equipment, and in 1920 that surplus included tens of thousands of motorcycles and men who knew how to ride them. Walmsley began reconditioning their machines, then buying crates of surplus Triumphs and selling them on.

The available sidecars offended him. Pram-shaped wickerwork encumbrances bolted to motorcycle chassis, the sort of thing that suggested the designer had last seen a vehicle in 1890 and assumed nothing much had changed since. He worked with his future brother-in-law in that same summerhouse and created something rather different: an octagonal bullet shape built from eight aluminium panels mounted on an ash frame, with wire wheels usually hidden by polished aluminium discs. People inevitably compared it to Zeppelins, which in 1920 was probably not the marketing angle you wanted, but it did at least suggest modernity.

He called it the Swallow Sidecar. His sister did the trimming until he married Emily Letitia Jeffries in 1921, when his wife took over. Production ran at perhaps one per week, sold locally for £28, with an extra £4 if you wanted the hood, lamp, and wheel disc. The first Swallow was registered at Stockport Town Hall on January 28, 1921. This remained a wounded veteran's occupation rather than an actual enterprise, something to fill the hours while his father contemplated retirement.

The Geography of Aspiration

When Thomas Walmsley sold his coal business in 1921 and moved the family to Blackpool, he was executing a manoeuvre every successful British tradesman of his generation would have understood immediately. Stockport meant work and smoke and neighbours who remembered when you started out hauling fuel. Blackpool meant you had stopped working and could afford to live somewhere eight million people a year went on holiday. J. B. Priestley later described it as "the great, roaring, spangled beast."

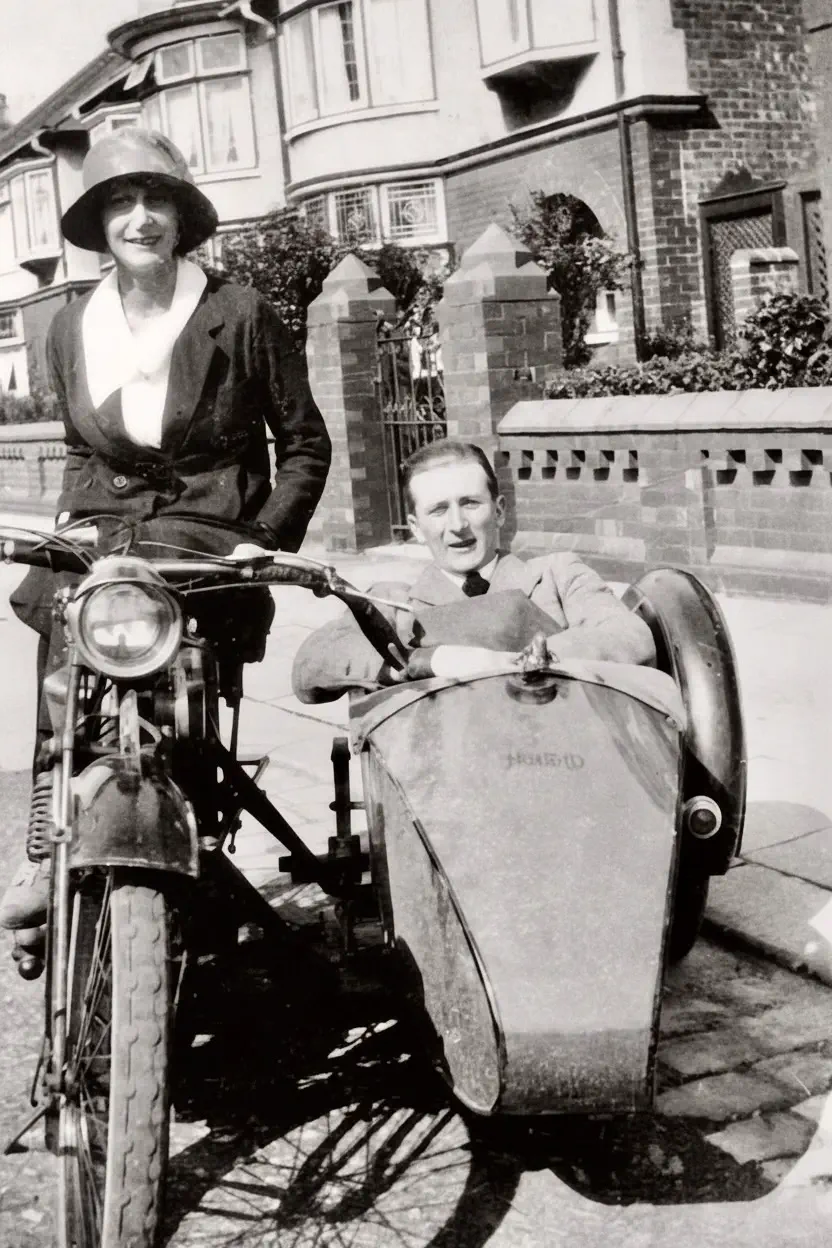

Number 23 King Edward Avenue sat on the better side of town, one of those solid, brick-built houses with grey slate roofs that announced their owners had done well enough to live where the sea air was respectable. At the end of the garden, next to a narrow lane, stood a small brick outhouse. William Walmsley set up his sidecar operation there, one per week, his wife handling the upholstery.

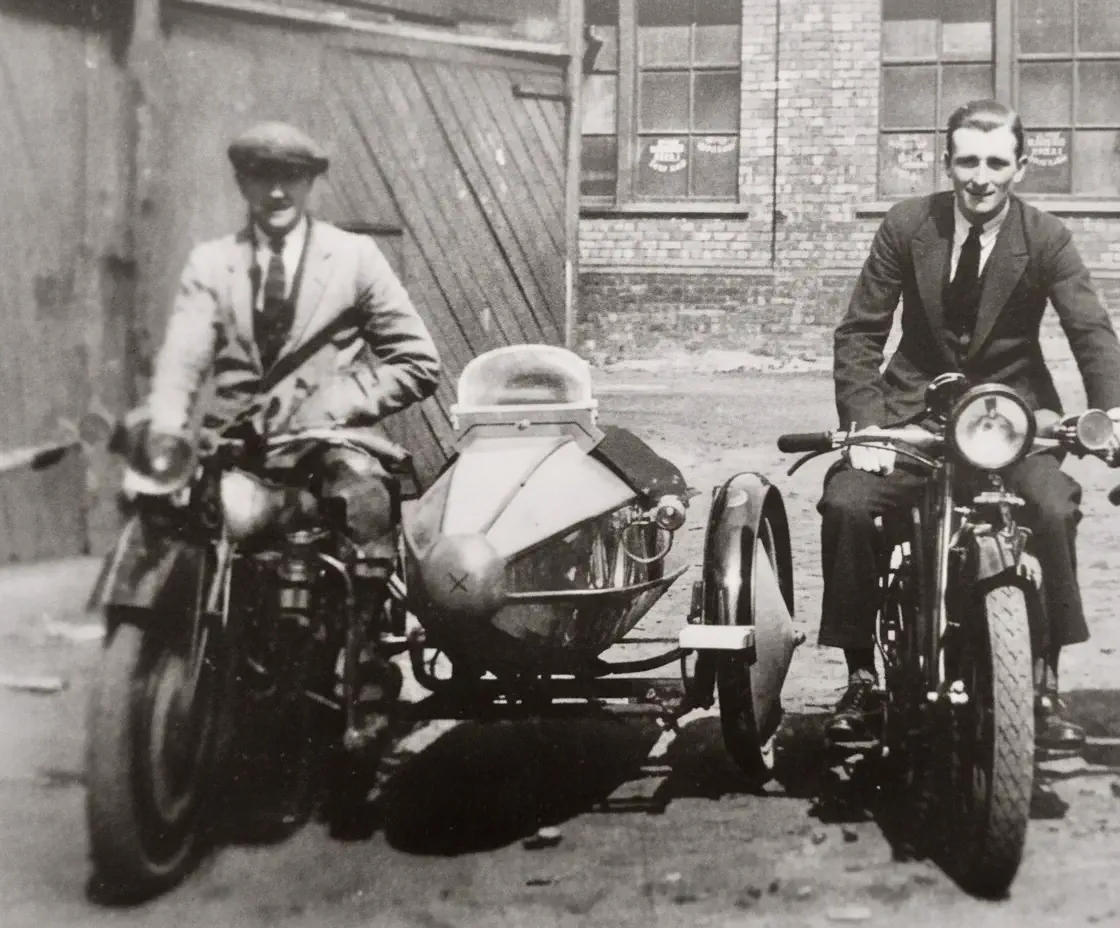

Almost in the next road lived the son of a piano dealer. William Lyons was twenty years old, which meant he was young enough to race motorcycles at Southport Sands and old enough to recognise opportunity when it appeared in aluminium. His father had come over from Ireland and built a successful music shop business. His mother was the daughter of a mill owner. Young William had attended Arnold School, served an apprenticeship at Crossley Motors in Manchester, and was now back in Blackpool selling cars for the local Sunbeam dealers while racing Nortons and Brough Superiors and generally behaving like a young man with no intention of spending his life selling pianos.

He noticed that dashing silver sidecar parked outside Number 23. Before long, he owned one himself. Then he had rather a lot to say about how many more could be sold if someone actually tried.

The Problem of Being Twenty

The age gap mattered. Walmsley was thirty in 1921, a war veteran content to build perhaps one sidecar per week in his shed. Lyons was twenty. He worked as a car salesman, raced motorcycles, and was possessed of the particular sort of energy that makes older men tired just watching. He saw immediately that the Swallow sidecar deserved better than local sales by word of mouth. The design was genuinely modern. The construction was solid. The market was almost certainly larger than one per week in Blackpool.

Walmsley agreed that expansion might be sensible and recognised that having someone around to handle the commercial side would be useful, as he remained far more interested in building things than in paperwork. They decided to form a company. Then they discovered that Lyons had not yet reached the legally required age of twenty-one.

So they waited. On September 4, 1922, the day after Lyons's twenty-first birthday, the Swallow Sidecar Company came into being with a £1,000 overdraft facility guaranteed jointly by Thomas Walmsley and William Lyons senior. The coal merchant and the piano dealer had both signed their names to the venture.

The Arithmetic of Risk

Britain that September was experiencing deflation of nearly fourteen percent. Prices were collapsing after the post-war boom. Unemployment was rising. The General Strike was four years away, but the conditions that would cause it were already visible. Thomas Walmsley understood transportation and manufacturing. William Lyons senior knew retail and customer preference. They could see potential in the product.

Blackpool's tourist boom had created enormous demand for leisure goods and transport, while the motorcycle market was expanding as ex-servicemen bought surplus machines. The sidecar transformed a motorcycle from solo transport into something a family could use. But everyone knew sidecars would vanish as soon as cheap cars became available, which they obviously would, probably quite soon.

The fathers signed anyway. Their sons had a decent product and ambitions that exceeded a shed in Blackpool. Sometimes that has to be enough.

From Summerhouse to Coventry in Six Years

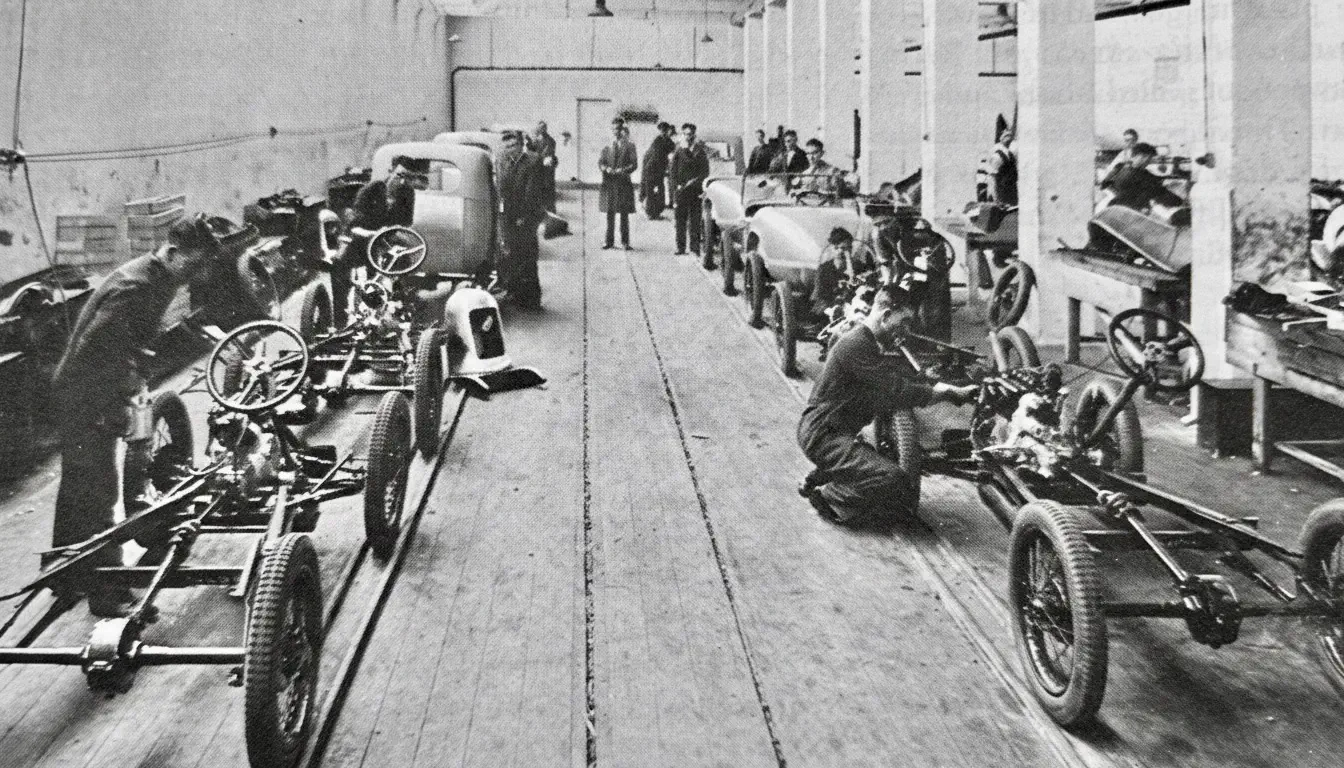

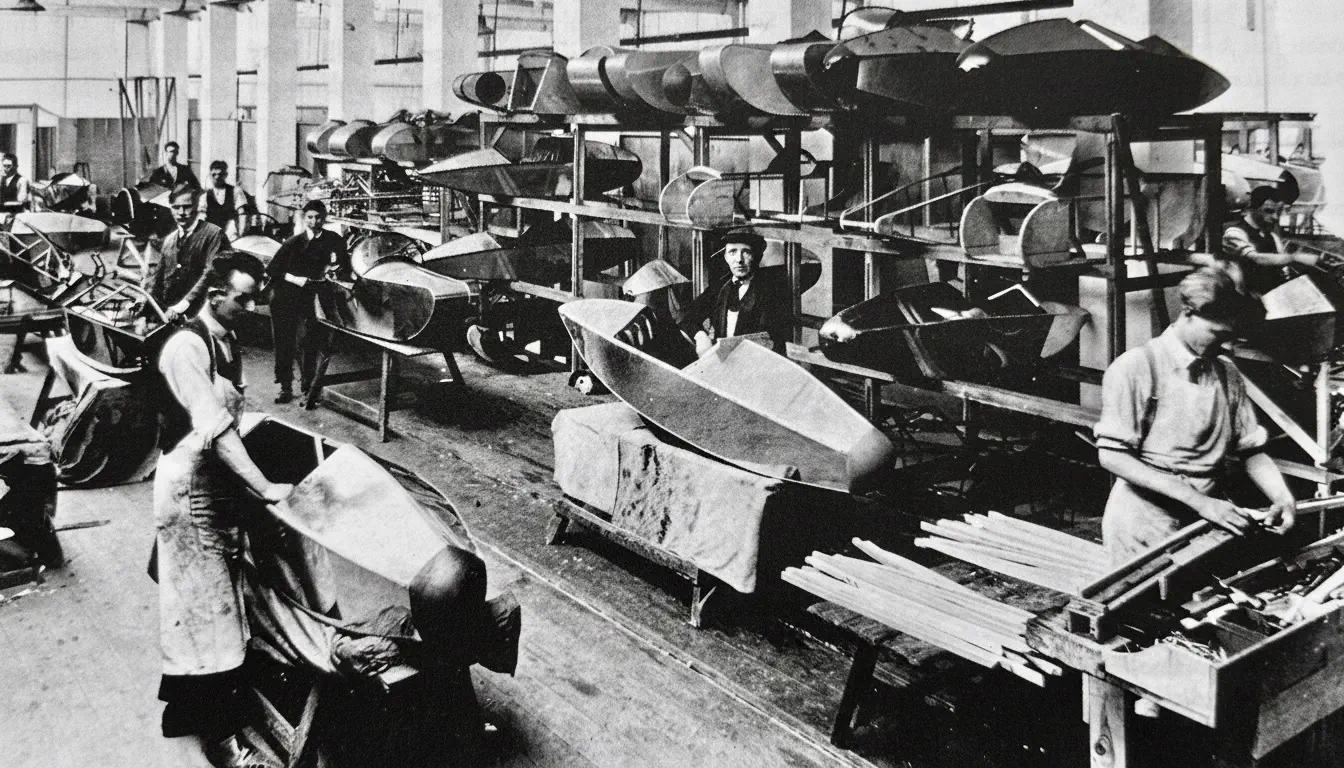

They leased premises on Bloomfield Road, hired half a dozen men, and watched production soar. Within a year they needed a warehouse on WoodField Road, then a building in John Street. Output crept towards one hundred sidecars a week. Everyone's predictions about cheap cars killing the market were correct, but the timing was optimistic by about forty years.

By 1926 they needed even larger premises. Thomas Walmsley sold his coal business to raise capital, purchased works on Cocker Street, and leased them to the company for £35 a year. The coal merchant liquidated the business he had built to fund his son's sidecar factory.

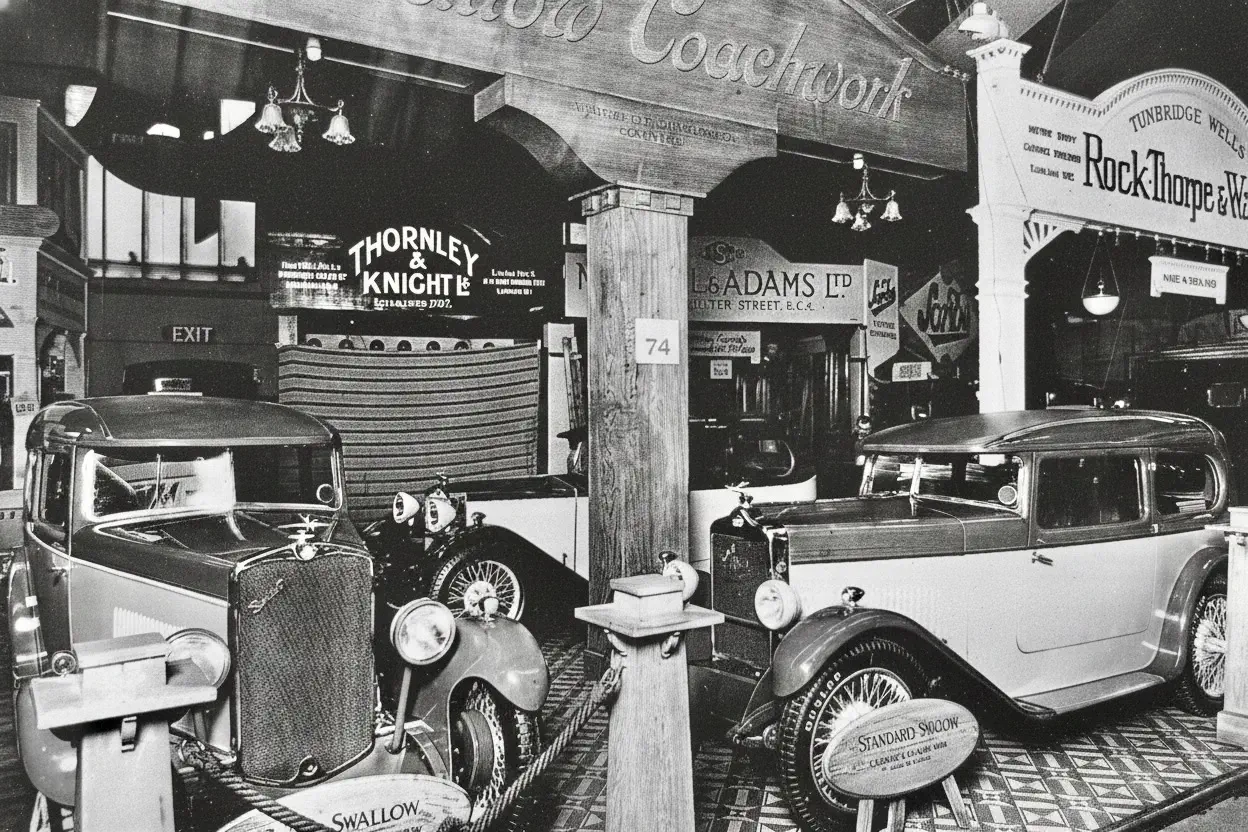

But Lyons and Walmsley were already looking beyond sidecars. The Austin Seven had launched in 1927, Herbert Austin's "motor for the millions," a proper small car rather than a glorified motorcycle with delusions. Swallow decided to acquire cheap chassis and fit them with expensive-looking coachwork. The Austin Swallow Seven appeared in May 1927 for £175, a pretty two-seater that looked considerably more expensive than its mechanicals suggested.

Henlys, the London dealer, ordered five hundred. Lyons drove back to Blackpool calculating how they were going to manage fifty cars a week when they were currently building twelve. By late 1927, Blackpool had become inadequate. The skilled labour was in the Midlands. Lyons drove to Coventry flat out, a trip that included the corners by his own admission. He found a former shell-filling factory at Foleshill and moved the entire operation by November 1928.

Production reached fifty bodies per week. Six years after formation, the sidecar company had become a coachbuilder employing skilled metalworkers in a proper factory. The trajectory suggested the fathers had backed the right combination of product and personnel.

The Divergence

William Walmsley grew increasingly uninterested in the business and eventually spent more time on his model railway than on coachbuilding. Lyons bought him out in 1935. Walmsley went on to build caravans, which suggests his instincts about what he enjoyed were consistent throughout. He preferred making things to running enterprises, which is fair enough.

The name Jaguar appeared in 1935 after Walmsley had left. Swallow had become SS Cars, which after 1945 became impossible for obvious reasons. The company would go on to define British sports cars for decades, building machines that looked like nothing conceived in a Blackpool summerhouse.

The Forgotten Underwriters

The founding of Jaguar is usually told as William Lyons’s story, which is understandable: he built the company and ran it for decades. Walmsley appears as a footnote, the craftsman who designed the original sidecar and left when the business became too businesslike. Both versions are accurate, but incomplete.

Almost nobody mentions the fathers, who gave them the chance by betting on aluminium bullets attached to motorcycles during an economic collapse. Thomas Walmsley died in June 1961, by which time the company his capital had helped create was building some of the most beautiful cars in the world. Lyons senior lived long enough to watch his son’s success, which is probably more satisfaction than most fathers get from signing a bank overdraft.