Aston Martin: The Savile Row Supercar

Aston Martin sells a very specific, very British fantasy: the idea that one can conduct acts of profound irresponsibility, usually involving speed, while looking like the most civilised person in the room. It is a brand that has perfected the art of financially ruinous elegance, a company that has famously gone bankrupt seven times. Its entire history is a glorious, lurching cycle of crisis, rescue, and the creation of another breathtakingly beautiful car, saved on each occasion by a new owner convinced that this time they can finally make a profit from building the world's most desirable grand tourers.

The Workshop Warriors

The company was founded in 1913 by Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford in a small London workshop. Martin had been racing tuned Singers at the Aston Hill Climb in Buckinghamshire with some success, which gave him the dangerous idea that he could build something better. The first car appeared in 1915, fitted with a Coventry Simplex engine, but the First World War arrived and stopped production before it could properly start.

After the war, they regrouped and over the next four years managed to build about 55 cars, mostly for racing, while accumulating debts at an alarming rate. Building exquisite cars by hand, it turns out, is the fastest way to go bankrupt. This is a lesson Aston Martin would repeat six more times over the next century.

Salvation arrived in the form of Count Louis Zborowski, the Polish-American millionaire whose father had died racing and whose mother was an Astor heiress. At 16, Zborowski inherited £11 million (about £1.5 billion today) in cash and chunks of Manhattan, which he proceeded to spend on speed. He poured over £10,000 into Aston Martin, raced their cars at Brooklands, and gave the tiny workshop something it desperately needed: legitimacy and a customer who actually paid his bills. When Zborowski died at Monza in 1924, aged just 29, he took the company's financial lifeline with him. Lionel Martin departed a year later, exhausted and broke.

The Bertelli Years

The company was rescued in 1926 by Augustus Bertelli and William Renwick, who had created a new 1.5-litre single overhead cam engine and needed somewhere to put it. Bertelli’s philosophy was simple: keep it light, make it handle, and prove it on the track. The 1929 International became the blueprint, agile enough for competition yet civilised enough to drive home afterwards.

Through the 1930s, Aston Martins raced at Le Mans and took class wins at hill climbs across Europe. The 1934 Ulster marked the height of that approach, a racing car with lights and a number plate. In 1932, Sir Arthur Sutherland took over and began building cars for wealthy gentlemen who preferred to arrive where they were going without being covered in oil.

By 1939, as Europe moved towards war, Bertelli’s team created the Atom, a prototype with independent front suspension and an early space-frame chassis, technology that would not appear widely for another decade. During the war, Sutherland drove it himself, waiting for peace and someone with the money and imagination to see its potential.

The Tractor Manufacturer

That person appeared in early 1947. David Brown, a Yorkshire industrialist who had made his fortune building tractors and gearboxes, spotted an advertisement in The Times for a "high-class motor business" and made enquiries. A few days later, he visited the Feltham factory and took the Atom for a drive.

He was impressed. The handling was superb, the chassis years ahead of its time, and the construction beautifully executed. The engine, a 2-litre four-cylinder pushrod unit, was hopeless. It had no real power, but the chassis, suspension, and space-frame construction pointed to the future. He bought Aston Martin for £20,500.

A few months later he acquired another struggling British maker, Lagonda, for £52,500. That purchase included a far greater prize: a superb 2.6-litre twin-cam straight-six designed by W. O. Bentley himself. Brown now owned two bankrupt firms, which sounded disastrous but was rather clever. He combined the Atom’s chassis with Lagonda’s engine and created the first proper David Brown Aston Martin.

The Two Litre Sports appeared in 1948, later known as the DB1. Only fifteen were built, but it set the formula: light chassis, sophisticated suspension, strong engine, elegant bodywork. The DB2 followed in 1950 and refined the idea into something genuinely desirable.

The 1950s brought steady progress. The DB4 arrived in 1958 with Touring of Milan bodywork and 140 mph performance. The DB5 followed in 1963 as a larger, more polished successor. These were cars for wealthy enthusiasts who valued engineering and understatement over showmanship. Production stayed modest, around a thousand cars a year from Newport Pagnell, yet the company had found its place: expensive, hand-built grand tourers capable of crossing continents at speed without fuss or fatigue, built for people with both taste and money.

David Brown took Aston Martin back to racing, and in 1959 the DBR1 won Le Mans outright, beating Ferrari. For a tiny British manufacturer with two hundred employees to defeat the Italian giants was an act of engineering audacity. It also proved that competition worked as development, though whether it ever worked as business remained uncertain.

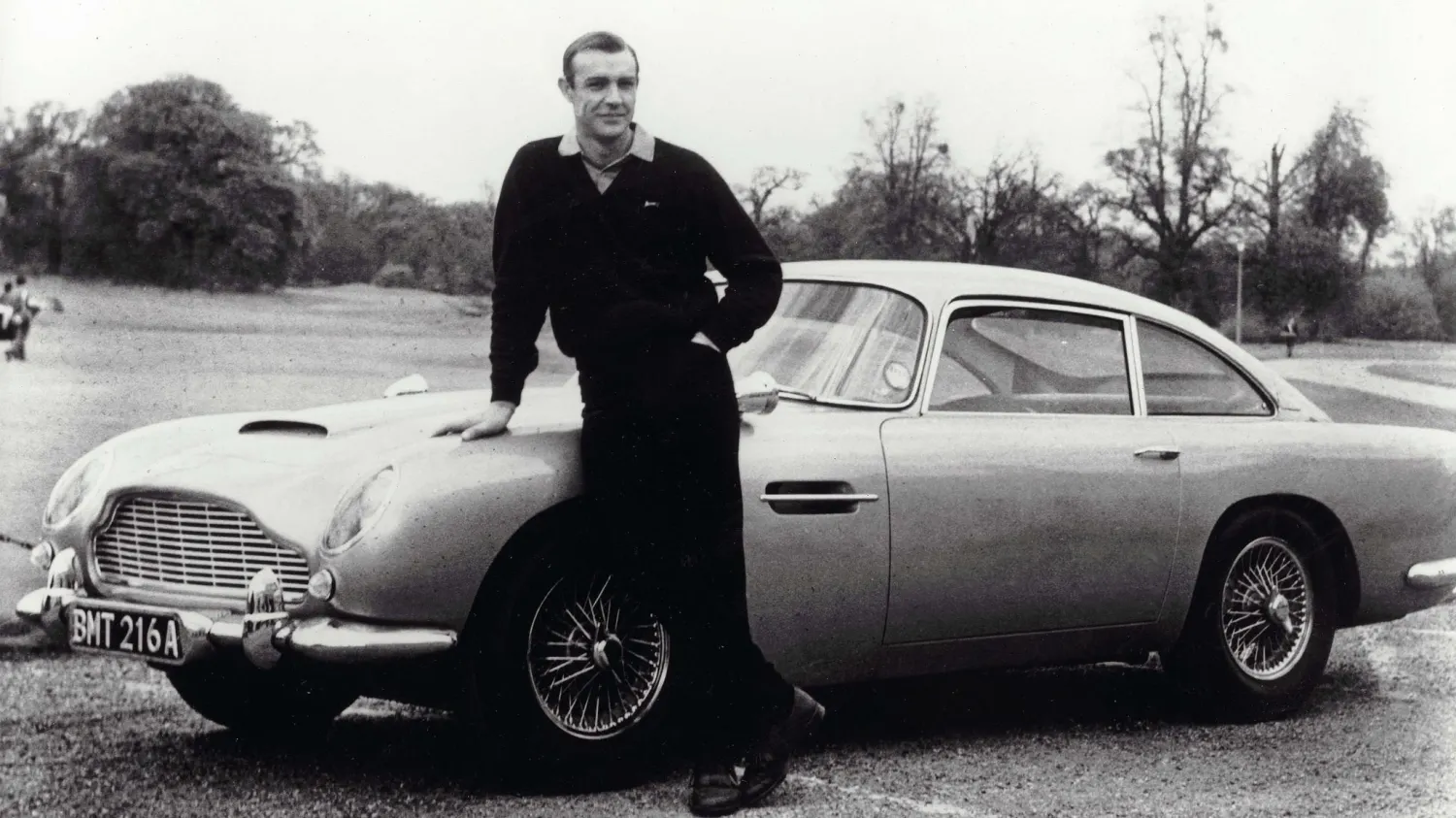

The Silver Birch Ejector Seat

In 1964, the DB5 appeared in Goldfinger, the third James Bond film. The producers needed a car that suggested sophistication so they chose a DB5, painted it Silver Birch, and fitted it with machine guns, revolving number plates, and an ejector seat. The film made the car more famous than any amount of advertising could have achieved. Every man in the Western world suddenly wanted an Aston Martin.

This created a peculiar problem. The DB5 transformed Aston Martin from a respected specialist into a global phenomenon practically overnight. But the Newport Pagnell factory was still building cars by hand at a pace that would embarrass a Victorian furniture maker. They now had brand recognition comparable to Coca-Cola but production capacity comparable to a village brewery. David Brown had won the lottery but lacked the infrastructure to collect the winnings.

The company tried to expand. The DBS arrived in 1967, a larger four-seater designed by William Towns with squared-off styling that suggested it had been designed with a ruler. Initially powered by the straight-six engine, it received a new 5.3-litre V8 in 1969. This engine, designed by Tadek Marek, would power Aston Martins for the next 31 years. The DBS V8 was ferociously fast, capable of 160 mph, which made it one of the fastest production cars in the world and prompted insurance companies to ask searching questions about the driver's mental stability.

The Difficult Years

In 1972, David Brown sold Aston Martin. He had poured his fortune into the company for 25 years, creating something magnificent in the process, but profitability had remained persistently elusive. What followed was a miserable period. The company changed hands multiple times through the 1970s, each new owner discovering that passion and balance sheets exist in different universes.

The decade produced some remarkable machines. The V8 Vantage of 1977 was Britain’s first true supercar, capable of 170 mph and quite able to frighten even seasoned drivers.

The same period also gave us the wedge-shaped Lagonda saloon, unveiled at the 1976 London Motor Show looking as though it had escaped from a science fiction film. Designed by William Towns with a fully digital dashboard, it promised the future. The electronics failed on the stand and kept up the act with impressive regularity for years afterwards. The Lagonda stayed in production for fourteen years, during which 645 examples reached owners wealthy enough to afford both the purchase and the repairs. Time magazine later listed it among the “50 Worst Cars of All Time”, describing it as a mechanical catastrophe. The verdict feels harsh. The Lagonda worked perfectly well, just not very often.

The early 1980s also saw the Bulldog, a mid-engined prototype with gullwing doors and a twin-turbocharged V8 producing 600 horsepower. It was designed to reach 237 mph and establish Aston Martin as the fastest production car maker in the world. Testing achieved 191 mph before Victor Gauntlett, who took control in 1981, recognised that a company on financial life support probably shouldn't be attempting land speed records. The Bulldog was shelved. It finally reached 200 mph in 2024, forty-four years later.

The American Rescue

In 1987, Ford Motor Company bought 75% of Aston Martin. For the first time in decades, the company had an owner with serious resources and modern manufacturing expertise. Ford invested heavily, built a new factory and dragged Aston Martin from its artisanal past into something resembling a contemporary car manufacturer.

The result was the DB7, launched in 1994. It was based on a Jaguar XJS platform, powered by a supercharged straight-six engine, and used components borrowed from various Ford parts bins. The door handles came from a Mazda. Purists were appalled. Customers bought them in unprecedented numbers. Over 7,000 DB7s were sold before production ended in 2004, making it comfortably the most successful Aston Martin in history. A V12 version arrived in 1999, and silenced most remaining complaints.

More significantly, Ford built a purpose-built factory at Gaydon in Warwickshire, which opened in 2003. The cars that emerged, particularly the DB9 and V8 Vantage, combined traditional Aston elegance with reliability that didn't require a mechanic on a speed dial. The DB9, launched in 2004, used aluminium construction and modern electronics whilst maintaining the essential character. The V8 Vantage followed in 2005, a smaller, lighter sports car that attracted younger buyers who had made money in technology or finance and wanted something more interesting than a Porsche.

In 2007, the DBS name returned for a flagship model that appeared in Casino Royale. The Ford years proved that Aston Martin could modernise without losing its soul, that investment and heritage need not conflict. It was the most stable period in the company's history, which naturally couldn't last.

The Modern Predicament

Ford sold Aston Martin in 2007 to a consortium led by Kuwaiti investors. The company continued developing new models: the four-door Rapide, the Vanquish, updated versions of the DBS. In 2013, a partnership with Mercedes-AMG provided engines and electronics. For a brief period, the company appeared on track and profitable.

Then, in 2018, someone decided a stock market flotation was a good idea. The company was valued at £4.3 billion. The share price collapsed within months as investors discovered what everyone else already knew: Aston Martin makes beautiful cars but terrible profits. By 2020, the company faced bankruptcy for the seventh time in its history.

Rescue arrived in the form of Lawrence Stroll, a Canadian billionaire who made his fortune in fashion by investing in Tommy Hilfiger and Michael Kors. Stroll led a consortium that invested £500 million, taking a 25% stake and becoming executive chairman. He also owned a Formula One team called Racing Point, which he promptly rebranded as Aston Martin for the 2021 season. The name returned to grand prix racing after 61 years, which was brilliant marketing.

The company also launched the DBX, an SUV that became its best-selling model by appealing to customers who wanted an Aston Martin but also needed to collect children from expensive schools. The DBX proved you could make a high-riding family car look elegant, which represented genuine progress.

But the old pattern reasserted itself. Development costs for new models spiralled. The transition to electrification required investment on a scale that made previous crises look modest. By 2025, Stroll had poured over £600 million into the company and was now selling Aston Martin's stake in the F1 team to raise additional capital. The team would keep the Aston Martin name through a sponsorship agreement, but the company needed money more than it needed ownership.

The Eternal Return

Aston Martin has faced bankruptcy seven times in 112 years. Each rescue has followed the same pattern: someone wealthy arrives, recognises that the world would be poorer without it, and writes enormous cheques to keep it alive. The benefactors have included a racing count, a tractor manufacturer, petroleum magnates, an American automotive giant, and a fashion billionaire.

The company is still building cars that make their owners feel slightly better about themselves, still teetering on the edge, still refusing to die. For a company that has spent a century selling the fantasy of elegance under pressure, there is something rather fitting about that.