Rolls-Royce: The Best Car in the World

In 1907, when most cars were noisy, unreliable contraptions that broke down every few miles, Rolls-Royce built one so mechanically perfect that the loudest sound at 60 mph was the ticking of the clock. This required levels of over-engineering that bordered on insanity. For more than a century, the company has refused to see the difference. The result is a marque that exists to prove a single point: that if you never compromise, you can build the best car in the world.

The Meeting at the Midland Hotel

The story begins with an encounter in Manchester on 4 May 1904 between two men who had absolutely nothing in common. The Honourable Charles Stewart Rolls was an aristocrat whose fellow students at Cambridge called him "Dirty Rolls" because he preferred engine oil to inherited dignity. Henry Royce was a working-class engineering obsessive who had sold newspapers as a boy and now worked 36-hour shifts without stopping because he couldn't bear to leave a design unfinished. Royce had just built three experimental cars that were unnervingly silent and beautifully assembled.

Henry Edmunds, a friend who understood that opposites sometimes make excellent partners, arranged the meeting. Rolls test-drove a Royce 10 HP back to London, woke his business partner Claude Johnson at midnight, and declared he had found "the greatest motor engineer in the world." They formalised Rolls-Royce Limited in 1906, dividing responsibilities with the precision of a Swiss watch. Rolls would charm wealthy customers. Royce would build impossible machines. And Johnson, who later gave himself the rather excellent title "the hyphen in Rolls-Royce," would make certain the world knew exactly how good they were.

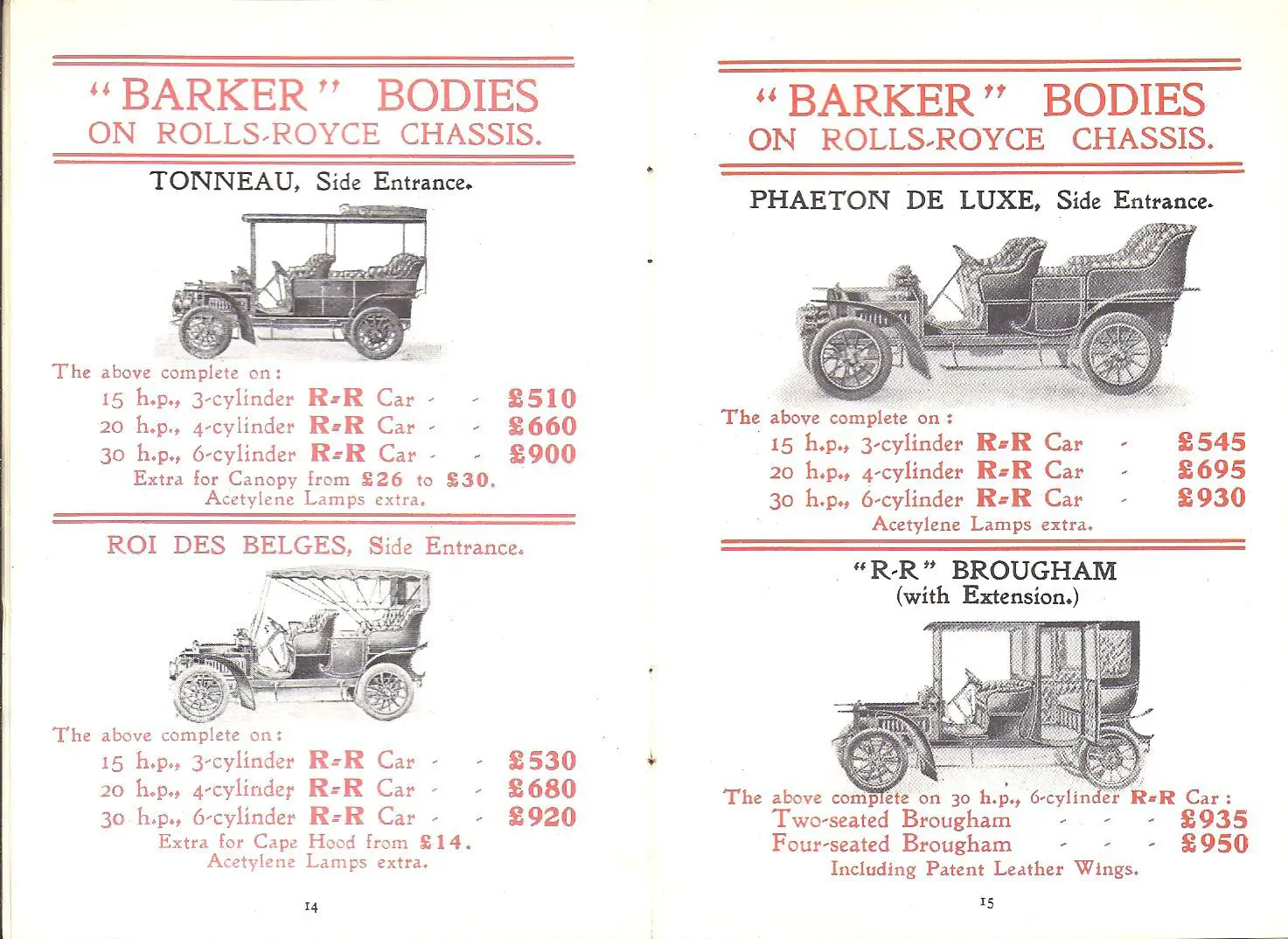

The Silver Ghost and the Risky Demonstration

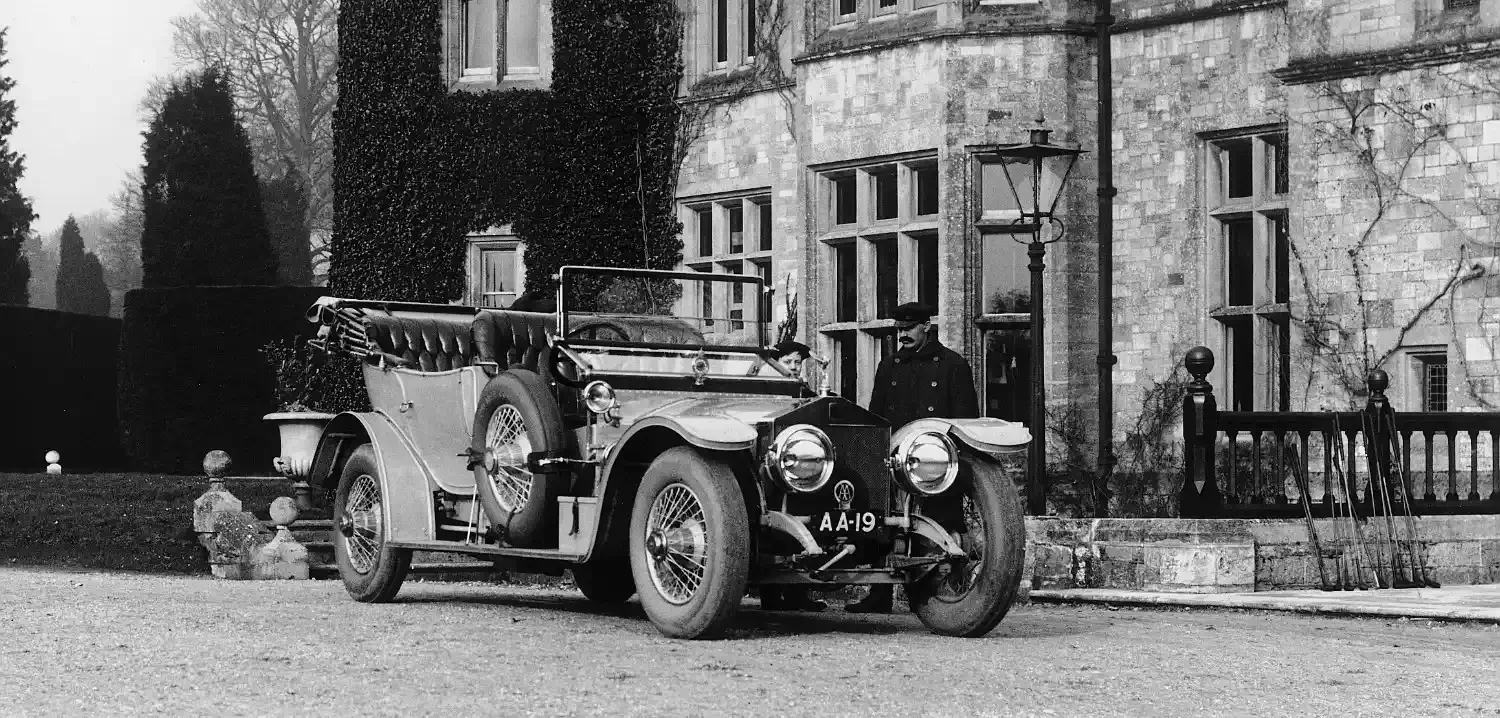

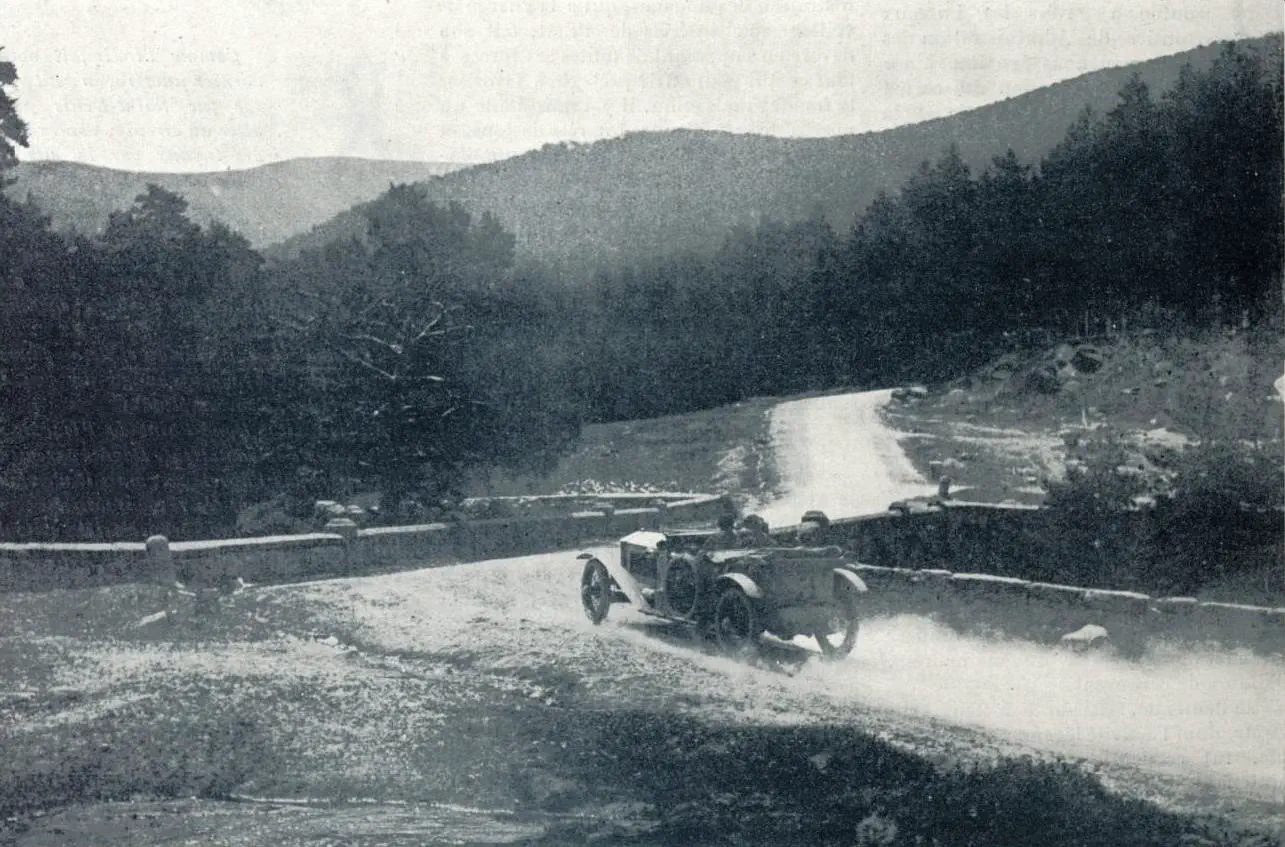

Johnson understood that the motoring public in 1907 believed all cars were fundamentally terrible. They were noisy, unreliable contraptions that broke down constantly and smelled of petrol. He decided to prove otherwise in the most dramatic way possible. Johnson selected the 12th chassis built, number 60551, and commissioned coachbuilder Barker to finish it in aluminium paint with silver-plated fittings. He christened it "The Silver Ghost" and then did something either brilliant or mad. He entered it in the Scottish Reliability Trial, where it covered 2,000 miles without a single failure. Then he drove the thing from London to Glasgow and back, 27 times, accumulating nearly 15,000 miles while Royal Automobile Club observers took notes.

When they stripped the car afterwards, the RAC found no measurable wear in the engine, gearbox, rear axle, or brakes. The total cost of maintenance and repairs for 15,000 miles came to £28, which is roughly what you might spend today replacing a single sensor on a modern German car. The motoring press, which had presumably been expecting the car to explode somewhere near Carlisle, instead declared it "the best car in the world." Johnson, who knew a good phrase when he heard one, made certain it appeared in every advertisement thereafter.

Production moved to a purpose-built Derby factory in 1908, where Royce refined his designs with pressure lubrication, dual ignition, and a crankshaft so obsessively engineered it split vibration between two three-cylinder banks. Between 1907 and 1926, Rolls-Royce built 7,874 Silver Ghosts. They are still running today, which tells you everything you need to know about Edwardian over-engineering.

The Aristocrat Who Preferred the Sky

While Johnson was busy establishing the company's reputation, Charles Rolls was losing interest in cars entirely. By 1907, he had discovered aviation and decided that flying was considerably more exciting than selling luxury vehicles to people who already had too much money. He made over 170 balloon ascents, which seems excessive even by Edwardian standards.

In February 1909, he suggested to the board that Rolls-Royce should manufacture Wright aeroplanes. They declined unanimously, probably because they were in the middle of building the world's finest cars and didn't fancy branching into machines that fell out of the sky. Rolls resigned as Technical Managing Director in April 1909. He remained on the board as a non-executive director, which in practice meant he could ignore the car business completely while pursuing his new obsession. On 2 June 1910, he became the first person to fly across the English Channel and back without landing, taking 95 minutes in a Wright Flyer while his parents watched from the Dover cliffs. King George V sent congratulations. The newspapers called him "the greatest hero of the day."

Five weeks later, on 12 July 1910, Rolls attended an aviation meeting in Bournemouth. The wind was gusting hard enough that one pilot had already wrecked his machine and another was begging the organisers to cancel the competition. They displayed the sort of Edwardian optimism that built empires and killed explorers, and decided to proceed anyway. During Rolls's descent from 100 feet, the tail section of his Wright Flyer separated from the aircraft. He sustained a fractured skull and died at the scene, becoming Britain's first powered aviation fatality at age 32. The partnership that created the world's finest car had lasted exactly six years. Royce, who rarely showed emotion, was reportedly in tears. Johnson and Royce would have to build the legend without the aristocrat who had lent it his name.

The Flying Lady and Her Tragic Muse

Johnson had a particular horror of vulgarity. In 1911, he noticed that wealthy Rolls-Royce owners were attaching their own mascots to the radiators. Fat policemen. Cartoon animals. Small dragons. This affronted his sense of propriety in the way that only truly awful taste can offend someone with good taste. He commissioned sculptor Charles Sykes to create something suitably elegant. Sykes had already created a private figurine for Lord Montagu called "The Whisper," which showed a woman holding one finger to her lips. The model had been Eleanor Thornton, who worked as Montagu's secretary and was, according to polite Edwardian euphemism, very close to his lordship despite his inconvenient marriage to someone else. Sykes adapted his earlier work, creating a windswept figure leaning into the wind with robes streaming behind. Johnson named it the Spirit of Ecstasy.

Until 1939, every single figurine was hand-finished by Sykes and his daughter Josephine, which meant that each one took ages to make and cost a small fortune. This was entirely acceptable to Rolls-Royce. Eleanor Thornton never saw her image become the most recognisable mascot in motoring. In December 1915, she was travelling with Lord Montagu to India when their ship, the SS Persia, was torpedoed by a German submarine off Crete. She drowned along with hundreds of other passengers. Montagu survived after spending days clinging to wreckage, and kept "The Whisper" on every Rolls-Royce he owned until 1929.

Johnson died suddenly in April 1926. Rudyard Kipling, who was his friend, wrote the memorial inscription: "He had the imagination to foresee and the energy to meet the needs of his country both on land and in the air." Royce, who had moved to Sussex for his health and spent winters in France, called him "the captain and we were only the crew." Royce himself continued designing from his sickbed until he died in 1933, his final work being the Merlin aero-engine that would later power Spitfires through the Battle of Britain.

The Company That Flew Too Close to the Sun

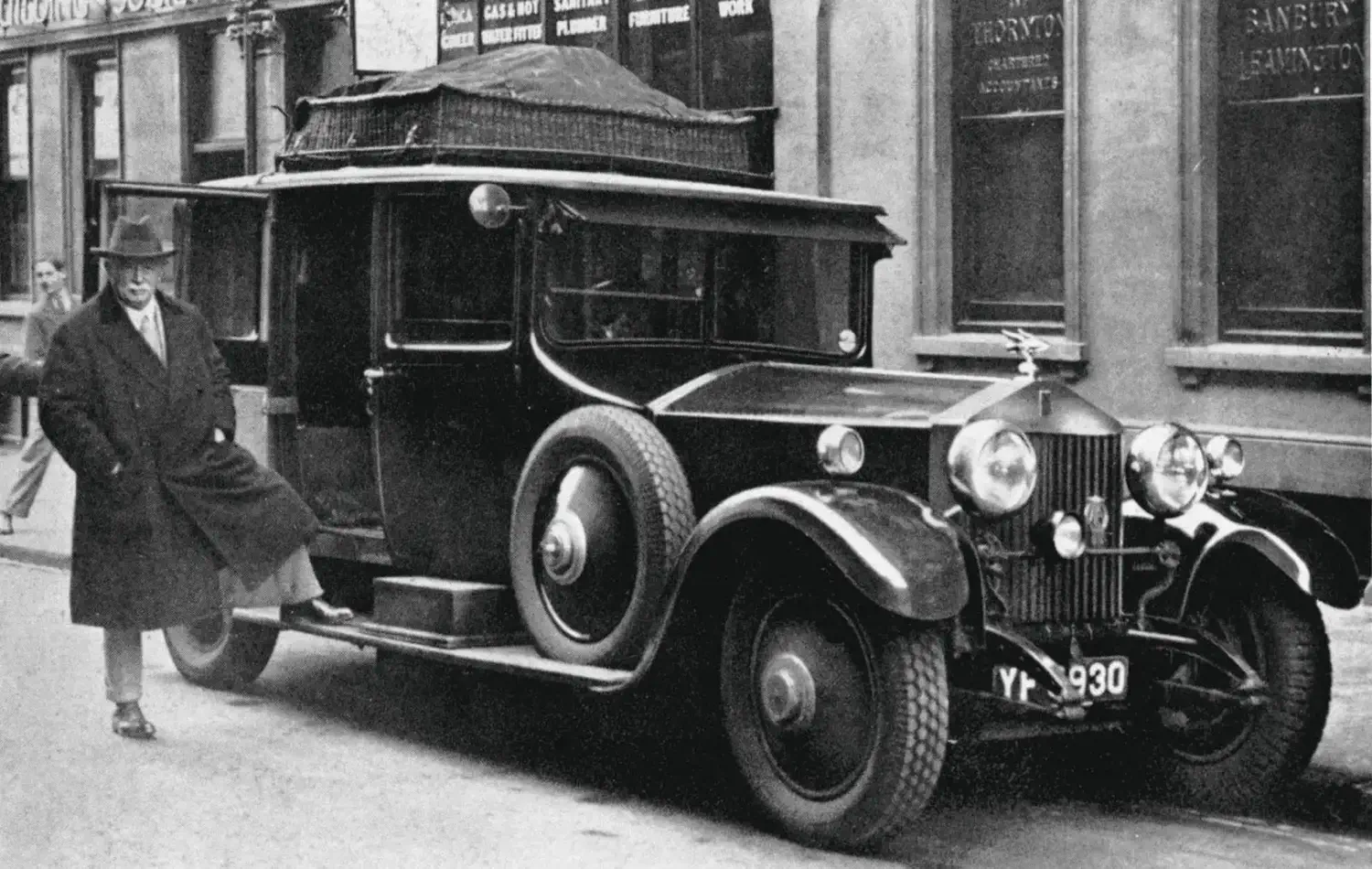

After World War II, car production moved to the Crewe factory, which had been built in 1938 to produce 25,000 Merlin engines and had employed 10,000 people at its peak. The post-war years brought the Phantom IV, which was built exclusively for royalty because, apparently, even Rolls-Royce had standards about who could buy their most expensive cars.

The 1960s brought the Silver Shadow with hydraulics licensed from Citroën, which was rather like Harrods asking Woolworths for design advice. Over 30,000 were built, making it the bestselling Rolls-Royce ever.

Then the company made a catastrophic mistake. In 1967, desperate to compete with American giants Pratt & Whitney and General Electric, Rolls-Royce committed to supplying Lockheed with a revolutionary jet engine called the RB211 for the new L-1011 TriStar. The engine would use carbon fibre fan blades, which promised tremendous weight savings. The blades failed bird-strike certification. This was a problem. A serious problem. Rolls-Royce had to redesign everything in titanium. Costs spiralled catastrophically.

By January 1971, the company that built the best cars in the world was completely insolvent. On 4 February 1971, the unthinkable happened: Rolls-Royce entered receivership. Prime Minister Edward Heath, who had campaigned on a platform of letting failing companies fail, was forced to nationalise it anyway because losing Rolls-Royce would be rather like losing the Crown Jewels. The car division, which had actually been profitable, was separated and eventually sold to Vickers in 1980. The world's most prestigious automotive brand had been brought down by an aero-engine it couldn't build on time.

The Most British Divorce Ever

By the 1990s, under Vickers ownership, Rolls-Royce Motors was chronically underfunded and being outsold two-to-one by its own Bentley brand. In 1998, Vickers decided to sell. BMW seemed certain to win. They already supplied engines and components. Their final offer was £340 million. Then Volkswagen appeared with £430 million and bought the lot: the Crewe factory, the Spirit of Ecstasy trademark, the radiator grille shape.

Except they hadn't bought the most important bit. The Rolls-Royce name and RR logo belonged to Rolls-Royce plc, the aero-engine maker, which wasn't part of the deal. The aero company had ongoing business with BMW and promptly licensed them the name for £40 million. This created an absurd situation. Volkswagen owned the factory and the Spirit of Ecstasy, but BMW owned the name. Neither could build a proper Rolls-Royce. BMW helpfully pointed out they could withdraw engine supply with twelve months' notice, leaving Volkswagen with a factory, some very nice badges, and no way to build the cars. After difficult negotiations, a solution emerged. From 1998 to 2002, BMW would supply engines while Volkswagen temporarily used the Rolls-Royce name. From 1 January 2003, BMW would build Rolls-Royce cars at a new facility, and Volkswagen would build only Bentleys. The last Rolls-Royce left Crewe in 2002. BMW constructed a new factory on the Goodwood estate in Sussex.

The Resurrection and the Electric Future

On 1 January 2003, BMW launched the new Phantom. It weighed 2,560 kilograms, produced 453 horsepower, and cost roughly the same as a decent house in Surrey. The glass of water balanced on the running engine still refused to spill. Today, Rolls-Royce has survived everything: two world wars, bankruptcy in 1971, and a corporate divorce so messy it required German diplomats to sort it out on a golf course. The current range includes the Ghost, Wraith, Dawn, the Cullinan SUV, and the all-electric Spectre launched in 2023.

Charles Rolls would have approved. In 1900, he predicted that electric cars would become "very useful when fixed charging stations can be arranged." It only took 123 years, but his prophecy finally came true. Rolls-Royce remains what it has always been: proof that if you refuse to compromise, throw enough money at a problem, and engineer everything to absurd standards, you can create the best car in the world. Whether anyone actually needs the best car in the world is another question entirely.