William Heynes: The Man Who Taught the Cat to Bite

William Lyons gave Jaguar its beauty, but beauty is only skin deep. The company’s soul, its thunderous heart and athletic stamina, came from another man entirely: William Munger Heynes. A quiet revolutionary who looked like a provincial librarian, he was the engineering genius who, with remarkable political skill, built a world-class, race-winning research department under the nose of Britain’s most famously frugal boss.

He arrived in 1935 from Humber, a company that built cars for people who found Rovers a bit racy. They were dependable, upholstered, deeply conservative machines for retired colonels and maiden aunts. SS Cars, by contrast, was a flamboyant coachbuilder with a reputation for style over substance. William Lyons, a stylist of genius, had been bolting his gorgeous bodies onto chassis with wheezy Standard engines, creating cars like the SS1, which had a bonnet long enough to host a dinner party yet performance that wouldn't trouble a determined cyclist. Heynes saw this weakness as the ultimate opportunity for an engineer to build a reputation from scratch.

The First Taste of Speed

Heynes knew better than to ask his new boss for money to design an engine from the ground up. Instead, he set out to improve the asthmatic Standard unit already in use. It was a robust side-valve design, solid as a brick, but it couldn't breathe.

He brought in Harry Weslake, the noted engine consultant, and together they designed a new overhead-valve cylinder head to sit on top of the old Standard block. The valves could now open properly, the mixture could flow, and suddenly the wheezy saloon engine became something rather different. The result was the SS Jaguar 100, a genuine 100-mph sports car where, for the first time in the company's history, the performance truly matched the film-star looks. This single act of engineering brilliance silenced the critics and, more importantly, proved to Lyons that investing in an engineering department was a very good idea indeed.

Fire-Watch Engineering

That pre-war success earned Heynes the political capital he needed for his real ambition: a proper engine of his own design. The war, inconveniently, put production on hold. But it provided the most bizarre development workshop in automotive history.

The Luftwaffe had decided that Coventry, the heart of Britain's industrial manufacturing, required thorough demolition. The resulting Blitz meant that senior staff, including Heynes and his two brilliant deputies, Walter Hassan and Claude Baily, had to take turns on fire-watch duty. This involved spending the night on the factory roof with a stirrup pump and a few sandbags, waiting for incendiary bombs.

While the city burned around them, these men took out their notebooks and sketched engines. They held technical seminars between explosions. The prospect of imminent incineration apparently focused the mind wonderfully on combustion chamber design. It says something profound about British engineering culture that death by firebomb was considered an acceptable backdrop for technical discussion. The Americans would have evacuated. The Germans would have built a bunker. The British made tea and drew valve trains.

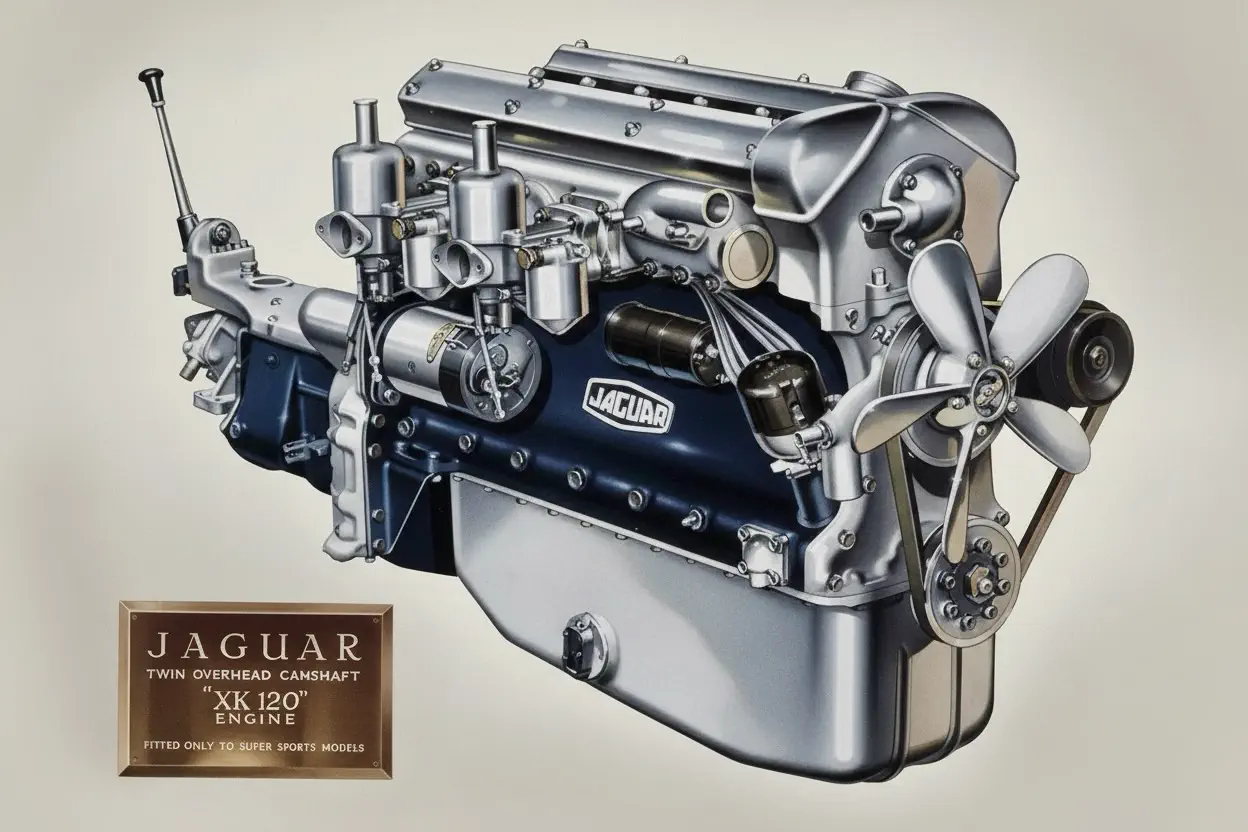

The engine they conceived was, for a mass-production car, pure science fiction. The XK featured twin overhead camshafts mounted directly on top of the cylinder head, eliminating the long chain of pushrods and rockers most engines still relied upon. Combined with hemispherical combustion chambers for efficient fuel burn, it was racing technology transplanted wholesale into a road car. Nobody else in Britain was attempting anything this ambitious in a production vehicle. It was a statement of intent.

The Frock That Became a Weapon

The engine was a masterpiece, but it didn’t have a home. Lyons, ever the showman, needed a theatre for the upcoming Earls Court Motor Show. His main focus was on the new saloon cars, but he knew an engine on a plinth wouldn’t grab headlines. He instructed Heynes to build a small, pretty two-seater to serve as a mobile display stand for the new powerplant. It was intended as pure eye candy, a limited-run folly to create a halo effect.

The car they produced was the XK120. It looked as if it had arrived from another planet. Lyons was promptly buried under a mountain of orders and blank cheques from dealers and wealthy individuals. He was forced to put it into production, which must have been a shock for a man who thought he was commissioning a show car.

The first hand-built, aluminium-bodied cars began to emerge in 1949. It was called the XK120 for a very simple reason: it could reach 120 miles per hour. That was a ludicrous, almost unbelievable speed for a production car at the time. To prove the claim, Jaguar took a production car to a closed stretch of road in Jabbeke, Belgium, and officially timed it at over 132 mph. Overnight, it became the fastest production car in the world.

Wealthy private owners immediately saw its potential. By 1950, they were racing XK120s everywhere. That year’s Le Mans entry proved crucial: Leslie Johnson, a privateer in his own virtually standard XK120, ran as high as second overall against purpose-built racing prototypes. The engine was a world-beater, even when bolted into a road car. Heynes now had the proof he needed.

Le Mans as a Secret Laboratory

He reframed the entire enterprise for Lyons. Le Mans, he argued, was a high-speed, twenty-four-hour test facility. It was a way to conduct radical research and development, funded by sponsors and prize money, far from the factory’s accountants. This was brilliant sophistry. The accountants saw racing and reached for their red pens. But research and development? That was legitimate. That was prudent. The fact that this R & D happened to involve French farmers watching cars thunder past their fields at 150 mph was merely incidental.

The C-Type was his first experiment. He took the XK engine and mounted it in a space frame, a lattice of thin tubes far stronger and lighter than the heavy steel chassis beneath road cars. Then he added disc brakes. While Ferrari relied on drums that would fade and fail, Heynes used an aircraft-derived system that stopped the car, every time, lap after lap.

Heynes made another crucial decision in 1950, one that would define Jaguar’s success for the next decade. He hired Malcolm Sayer from the Bristol Aircraft Company. Sayer was an aerodynamicist and mathematician who had spent the war calculating airflow over bomber fuselages. This was the real breakthrough: Heynes understood that racing cars had to cheat the wind.

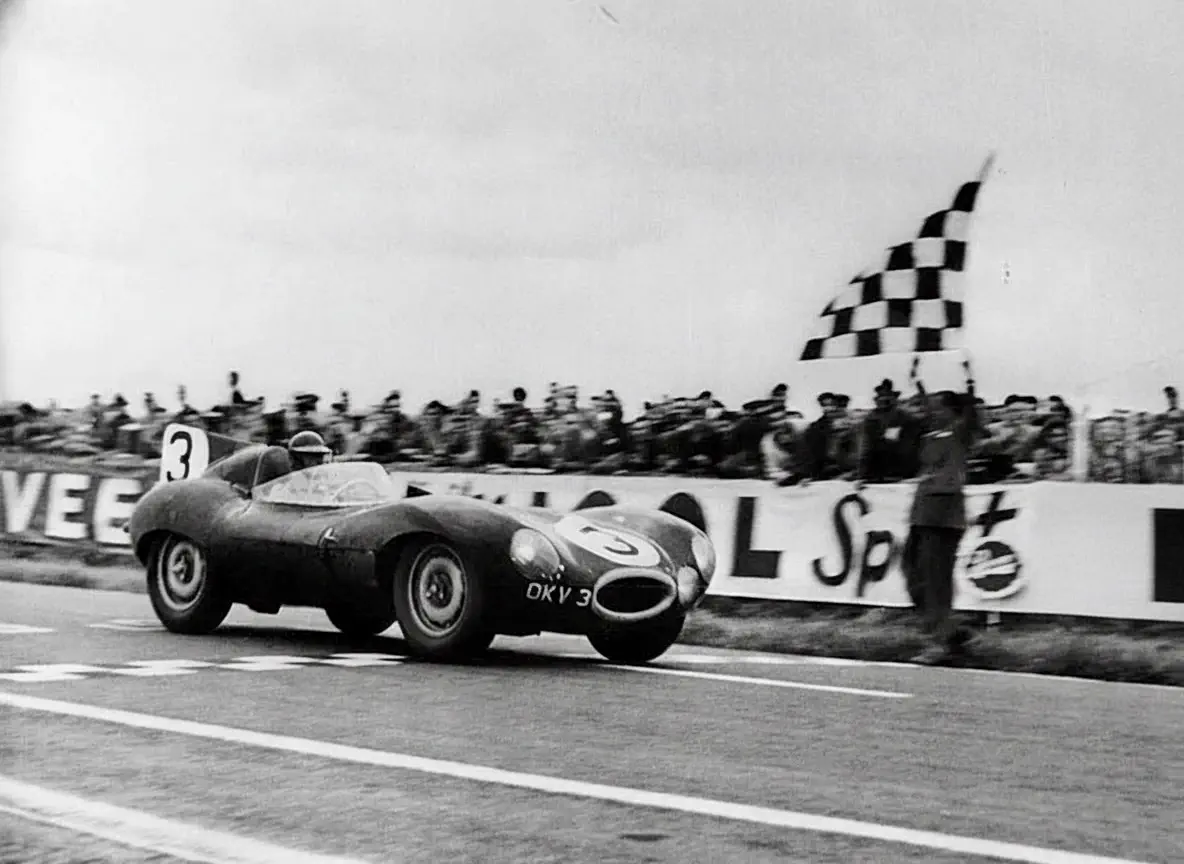

Sayer approached the C-Type body as he would an aircraft component. He calculated instead of sketched. While Lyons contributed styling details, the fundamental shape was pure mathematics. The C-Type’s smooth, low body became the first British racing car designed with true aerodynamic principles rather than intuition and a tape measure. The 1951 and 1953 Le Mans victories vindicated Heynes’s approach: hire the right specialists, give them proper tools, and let them solve problems scientifically.

The Mathematician's Masterpiece

The D-Type took Sayer into truly radical territory. Heynes abandoned the space frame entirely and adopted an aircraft-style monocoque tub. Its central structure was a stressed-skin shell, with the engine and front suspension mounted on a separate subframe. This was fighter-plane construction philosophy applied to a racing car.

The D-Type dominated Le Mans, winning in 1955, 1956, and 1957. Sayer’s aerodynamic efficiency made the car faster than its rivals with the same power and more stable at speeds that made other cars frightening to drive. This was mathematics defeating intuition, and it established the principle that would define Jaguar’s greatest achievement.

The Team Nobody Remembers

Heynes retired in 1969, just after the disastrous merger into British Leyland. It was a fitting time to leave. The age of the autocratic boss who trusted his engineers was over. The committee of accountants had arrived. For men who had spent decades quietly building icons, there was nothing left to accomplish. The game had changed, and not for the better.

The XK engine Heynes designed during those fire-watch nights went on to power Jaguars for nearly forty years. The monocoque construction he pioneered at Le Mans became industry standard. The disc brakes he championed became universal. Sayer’s mathematical approach to aerodynamics shaped an entire generation of sports car design. Their influence on automotive engineering was profound and enduring.

Yet William Lyons has a statue, books, documentaries. Heynes has a footnote in the history books and the quiet respect of engineers who understand what he achieved. Perhaps that suited him perfectly. Recognition was never his goal; the work itself was.