William Lyons: The Autocrat of Style

Sir William Lyons was a man of magnificent contradictions. Here was an individual who dressed with the sombre precision of a provincial bank manager, a man famously so careful with a pound coin it was a miracle he ever let one go. He was a Blackpool businessman, son of a music shop owner, who somehow managed to cultivate the impeccable air of a landed Warwickshire squire. And this man, this shy, formal, pathologically frugal autocrat, possessed an animal instinct for the most sensuous, traffic-stopping, and wantonly glamorous shapes in automotive history.

Lyons was, in short, a grand illusionist. He could not draw a technical blueprint, he was no engineer, but he built an entire empire by understanding one profound, human truth: people will forgive almost any flaw if the package is beautiful enough. He mastered the glorious alchemy of turning a low-cost, mass-produced chassis into a high-profit margin, all through the simple application of a perfect curve. He was the man who sold champagne style to a public on a beer budget, and in doing so, made himself a legend.

The Blackpool Revelation

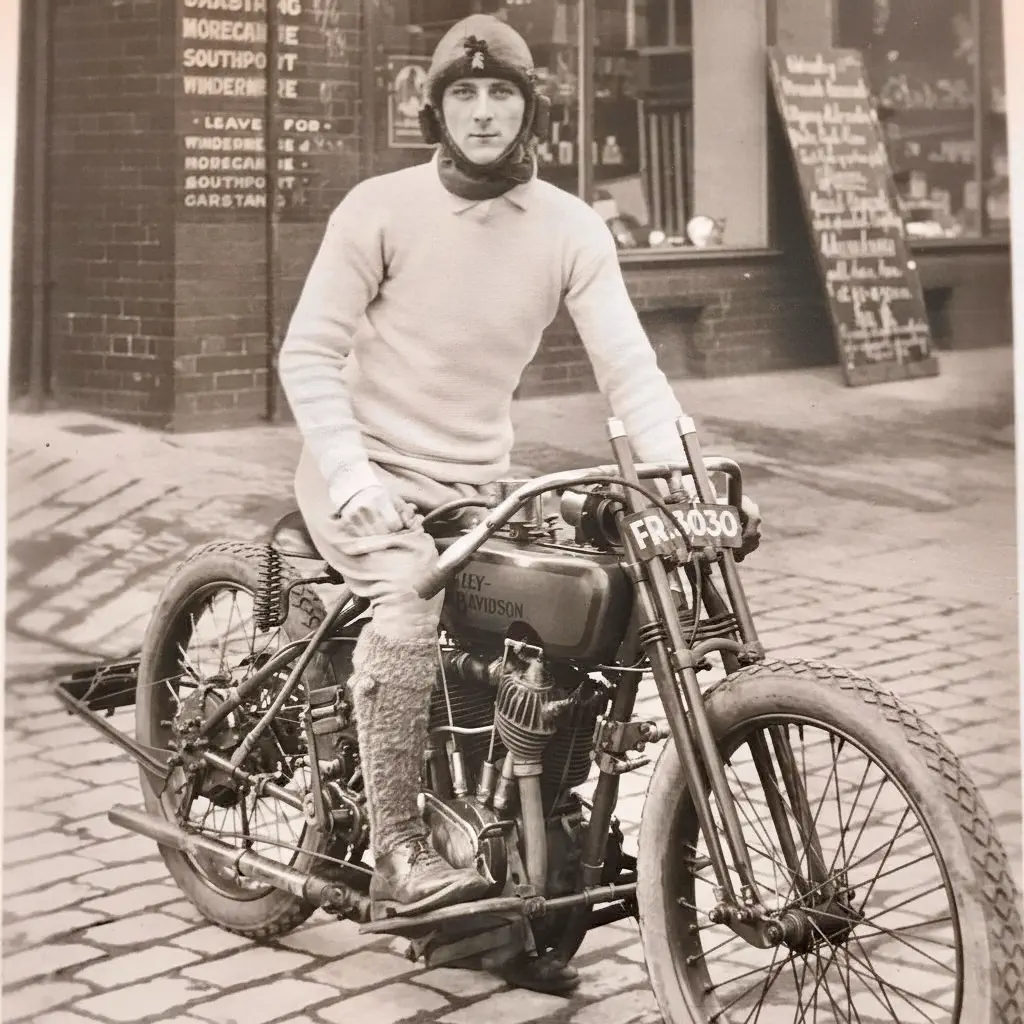

The Lyons method was pure Blackpool. His story begins there in 1922, in Britain's capital of affordable spectacle. Blackpool was, and is, a town built on seaside amusements, dazzling lights, and the fundamental principle of giving the working man a healthy dose of glamour for his shilling. This was the commercial air Lyons breathed, and it shaped his entire philosophy.

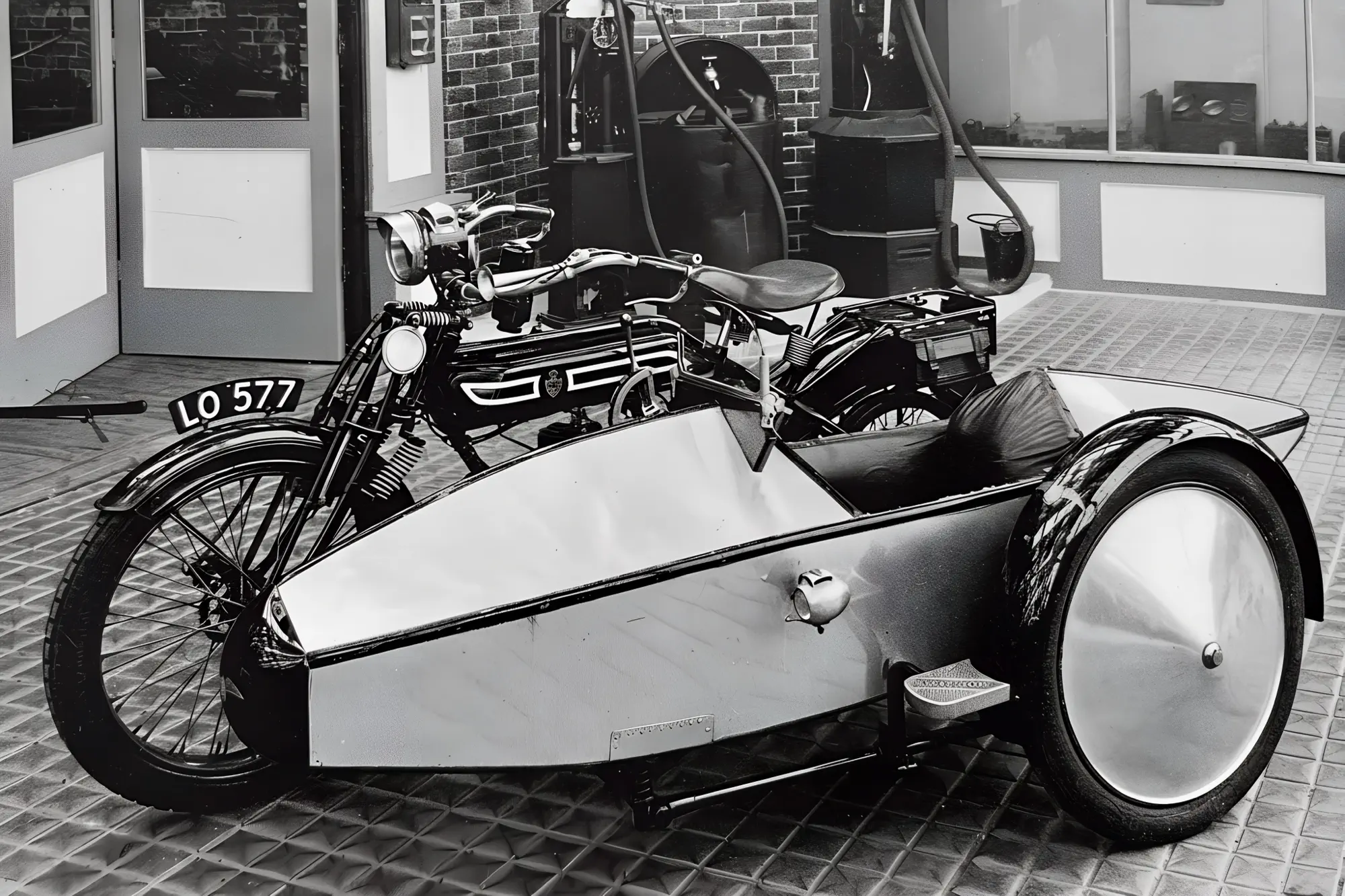

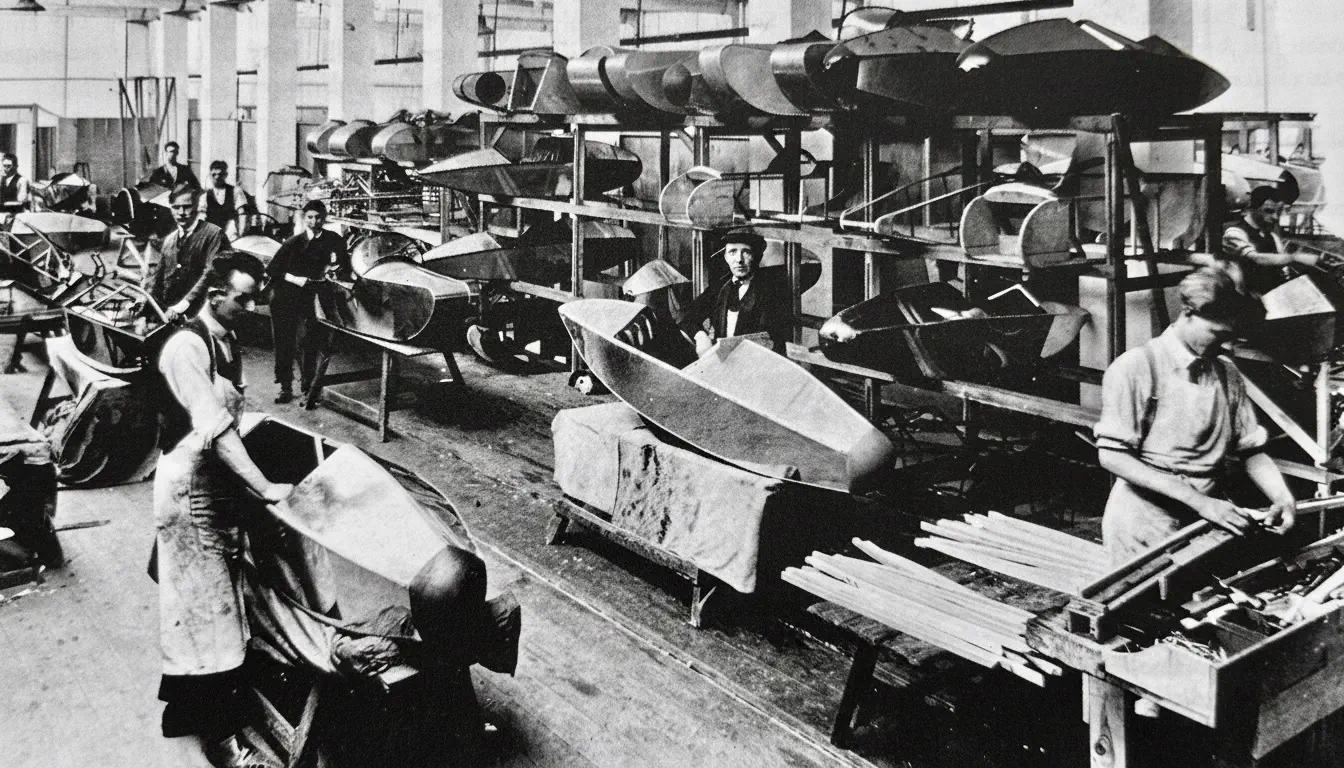

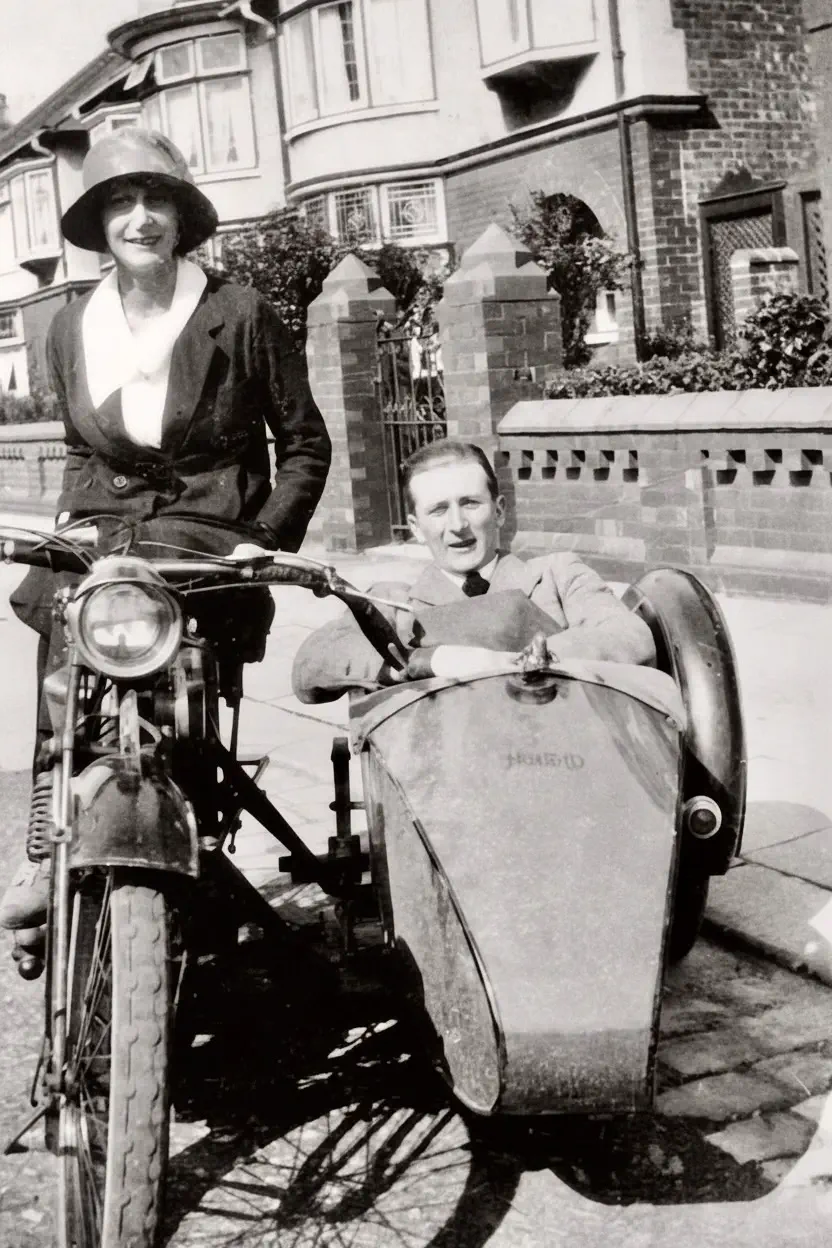

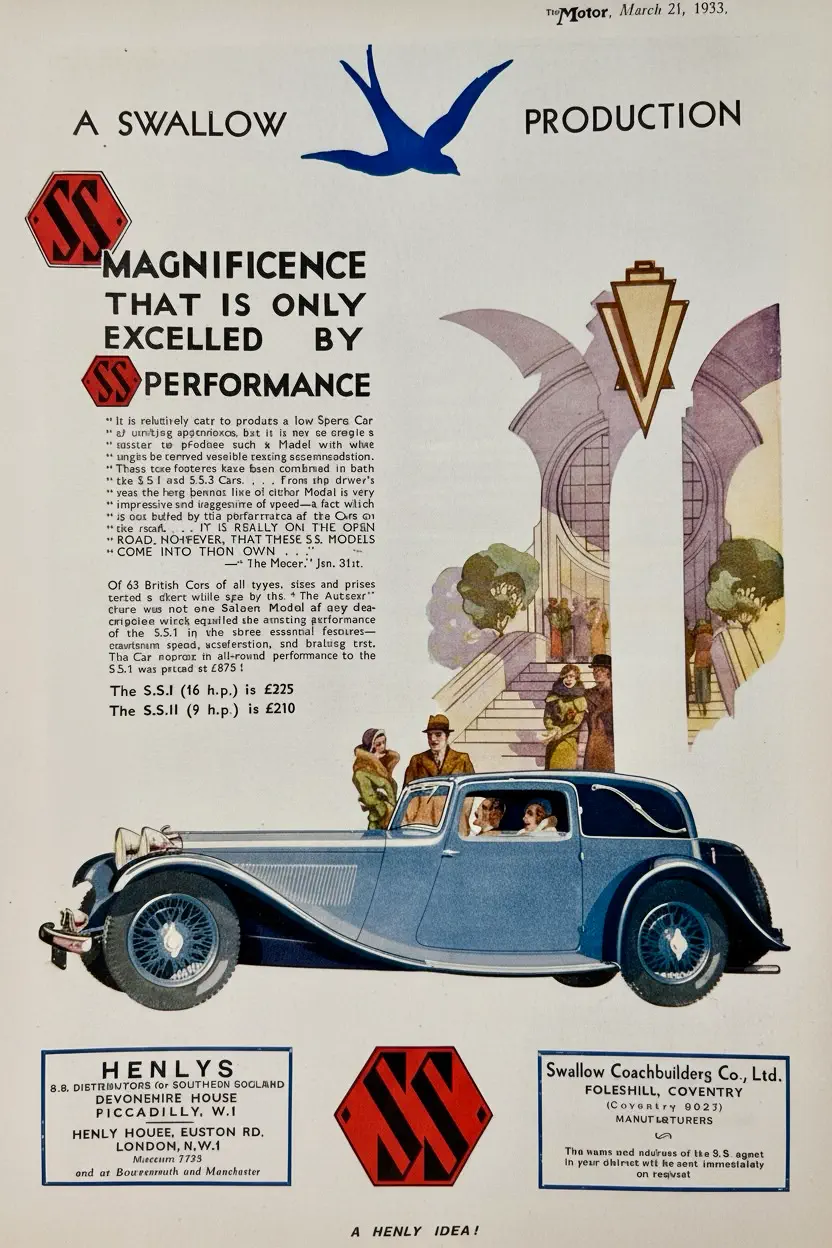

He began, alongside his partner William Walmsley, with motorcycle sidecars. Walmsley was the tinkerer, a man happy to craft things. Lyons was a man of ambition. They saw that the sidecars people attached to their motorcycles were, as a rule, hideous wooden boxes, purely functional and entirely joyless. Swallow Sidecars were nothing of the sort. They were sleek, aluminium, Zeppelin-shaped fantasies. They were no better-built than the competition, but they looked a thousand times more expensive. He charged a handsome premium, and the public, delighted to buy a piece of the dream, paid it with pleasure. He had learned his trade in the spiritual home of the seaside postcard, and it taught him that flash, applied correctly, is cash.

This Blackpool method was soon applied to cars. He took the humble Austin Seven, a car with all the visual drama of a garden shed, and clothed it in a long, low body that made it look like it had just arrived from the French Riviera. It was a magnificent con-trick.

His partnership with Walmsley could not last. Walmsley was content; Lyons was constitutionally incapable of it. In 1928, he moved his young family and thriving business to Coventry, a shark headed for bigger waters, ready to unleash his formula on the established and deeply stuffy British motor industry. They eventually went their separate ways in 1934, amicably, and Lyons went on to build an empire.

The Great Post-War Commotion

The pre-war SS cars cemented Lyons’ reputation. They were glorious-looking things, often built around dull but reliable Standard engines. They promised continental flair for the price of a modest Humber. Then came the war, after which the "SS" initials, for obvious reasons, were quietly dropped. The company re-emerged as Jaguar Cars.

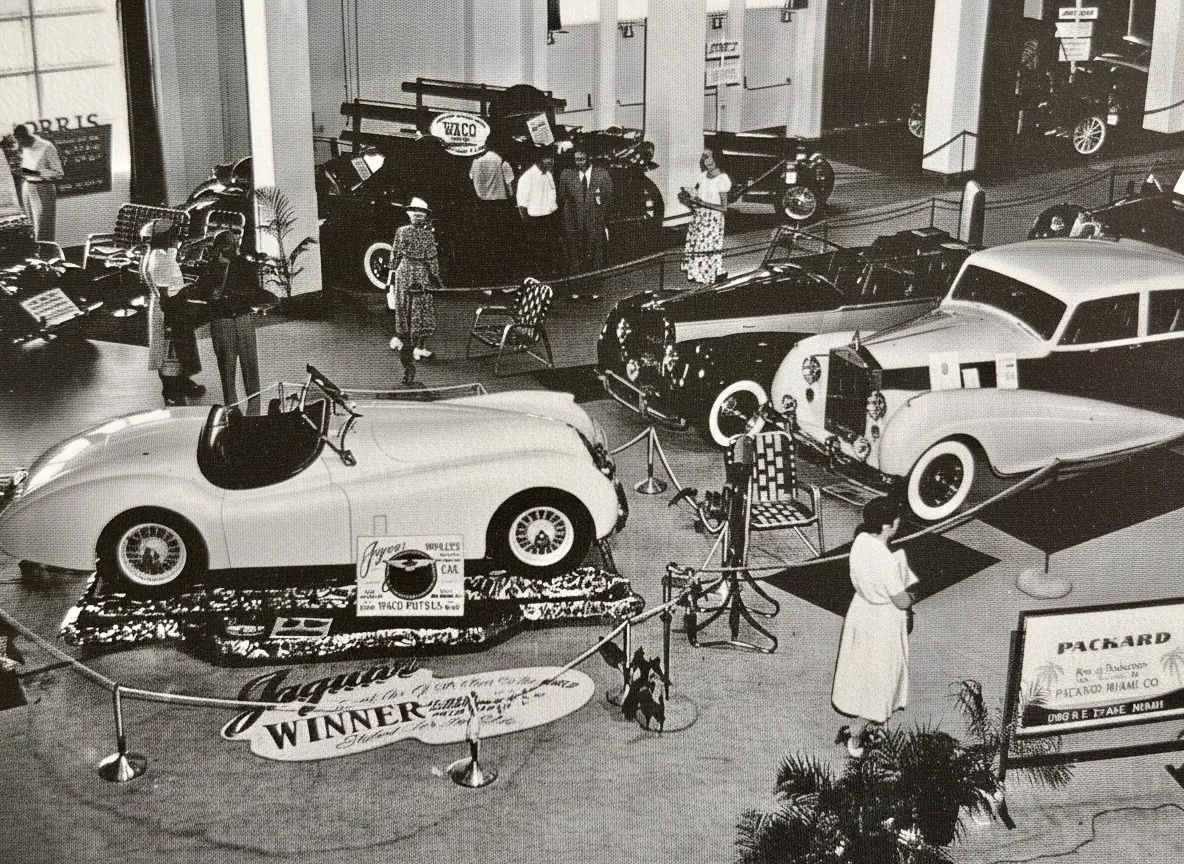

The post-war 1948 Earls Court Motor Show was the scene of his masterstroke. He had a magnificent new engine to display, the twin-cam XK, a genuine world-class piece of engineering. But Lyons knew that an engine on a plinth only excites men in brown coats. To cause a commotion, he needed theatre. In a frantic hurry, his team, led by his brilliant chief engineer William Heynes, panel-beated a two-seater body to wrap around it. It was only meant to be a showpiece, a bit of bait to lure people to the stand so he could sell them his sensible saloons.

The car, the XK120, caused a public breakdown. People had never seen a shape like it. In a Britain of drab, upright, recycled pre-war designs, here was a piece of alien sculpture. It was so low, so fluid, so utterly perfect in its proportions that it made every other car on the stands around look like a piece of vintage farm equipment. The 120-mph top speed was almost incidental. The real shock was the price: £1,263. It was an act of magnificent commercial aggression. He was, effectively, offering a Ferrari for the price of a Rover. The company was crushed under thousands of orders for a car it had no idea how to build in volume. Lyons, the parsimonious showman, had accidentally created an icon.

The Tyrant's Method

This triumph established the permanent civil war that defined Jaguar for thirty years. On one side stood his engineers, men like Heynes and the aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer, who had to wrestle with tiresome realities like physics, metallurgy, and the average size of a human. On the other side stood "Mr Lyons," who cared only for the line.

His method was the stuff of legend. After his team had prepared a full-size clay model, Lyons would enter the studio, Homburg hat in place, and conduct a funereal-paced walk around the shape. He would squint. He would ponder. Finally, he would point his umbrella. "That roofline," he would declare. "It needs to be an inch lower."

His engineers would protest. They would explain, with diagrams and, surely, some exasperated sighs, that lowering the roof meant a human head would no longer fit. Or that the rear doors were now unusable. Or that the windscreen wipers would have nowhere to go. Lyons would listen patiently, nod, and say, "I am sure you will find a way." Then he would leave.

This single-mindedness is what gave his cars their drama. It is what produced the absurdly long bonnet of the E-Type, a car that is, visually, almost entirely engine and driver. It is also what gave his cars their reputation for magnificent fragility. When most of the money and effort goes on the shape, there is not always much left over for the internals. A Lyons-era Jaguar was a car that would make you the envy of your neighbours right up until the moment it deposited its oil on their driveway.

The Final, Ironic Surrender

He produced his two final masterpieces, the E-Type in 1961 and the XJ6 saloon in 1968. The XJ6 was perhaps his purest expression: a car that looked, drove, and felt like it cost three times its asking price - and which possessed a Lucas electrical system with all the reliability and longevity of a cheap Christmas light.

But the fire was fading. The company's future, once a clear dynastic path, had been shattered in 1955. His only son, John, was killed in a car crash on his way to Le Mans to watch his father's team compete. Lyons, a devoted family man beneath the autocratic shell, was devastated. The line of succession was gone.

Lyons, the supreme autocrat, the man who never compromised on a curve, made his one, fatal compromise. Worried about the future and the chaos of the British motor industry, he merged his company into the sprawling, dysfunctional, strike-ridden bureaucracy of British Leyland in 1966. The autocrat had voluntarily subjected himself to a committee. And not just any committee, but a committee that thought beige was a rather racy colour and that the Austin Allegro was a bright idea. He had given his crown to a troupe of clowns.

The Shepherd

He retired in 1972, horrified at what he had unleashed. He returned to his grand home, Wappenbury Hall- the squire persona now complete - and transferred his obsessive perfectionism from cars to livestock. He spent his final years as a farmer, breeding prize-winning Suffolk sheep and Guernsey cattle. One can only assume he spent his evenings in the fields, umbrella in hand, critiquing their proportions.

William Lyons died peacefully at home in 1985. He proved that while engineering is functional, beauty holds the greater power. He understood something essential about the British psyche: everyone wants the thrill of champagne, even if they can only afford beer. His genius was to bottle that desire, and for it, he will be remembered forever.