The Divorce That Built an Empire and Killed an Industry

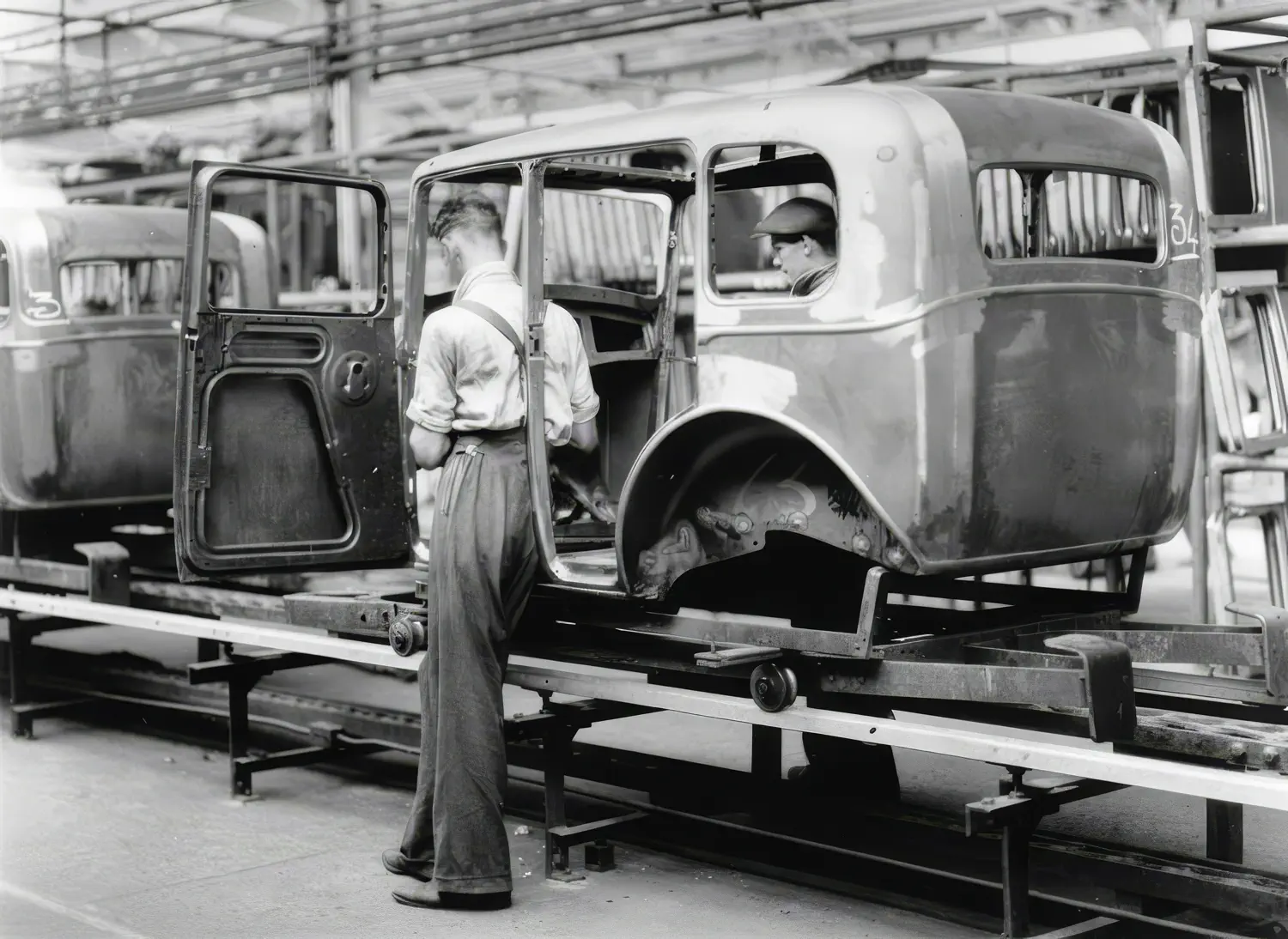

In the 1920s, British coachbuilders hammered metal panels over wooden frames with the sort of patient craftsmanship that would cause a modern production manager a heart attack. Each car body emerged as a unique snowflake of inconsistency, depending largely on whether your panel beater had enjoyed his breakfast or nursed a hangover. Across the Atlantic, Edward G. Budd had invented something faster and infinitely more reliable: enormous presses that could stamp out identical skins in seconds, then weld them together into proper all-steel bodies.

William Morris, a man who understood that money talks louder than tradition, saw this American efficiency in 1925 and decided he wanted it. The following year, he formed the Pressed Steel Company as a joint venture with Budd and the financiers at J. Henry Schroder & Co. A vast factory rose at Cowley, directly opposite Morris's own plant, connected by a special bridge across the road. It looked perfect on paper. Two industrial titans, British pragmatism meets American know-how, and a future of profitable mass production stretching into the sunset.

The Divorce

The partnership didn't last long, to put it mildly. Morris and Budd were both accustomed to getting their own way, and neither was keen on changing. The problems started immediately. British steel mills couldn't produce sheets large enough for Budd's massive presses. When they finally managed it, imported American steel was still 25 per cent cheaper. Morris wanted Pressed Steel exclusively for his cars. Budd, quite reasonably, wanted to sell bodies to anyone with a chequebook.

By May 1930, the relationship had deteriorated so completely that Budd dragged Morris to the High Court. The judges sided with Budd in what must rank as one of the more expensive lessons in partnership law. Morris was ordered off the Pressed Steel board, forced to surrender his shares, and left watching from across the road as his former partner began selling bodies to his competitors. Morris lost every penny he'd invested and spent the rest of the 1930s building his own pressing plant right next door.

Five years later, Budd sold up to British interests and withdrew entirely, leaving Pressed Steel as an independent operator with the most advanced body-making technology in Britain.

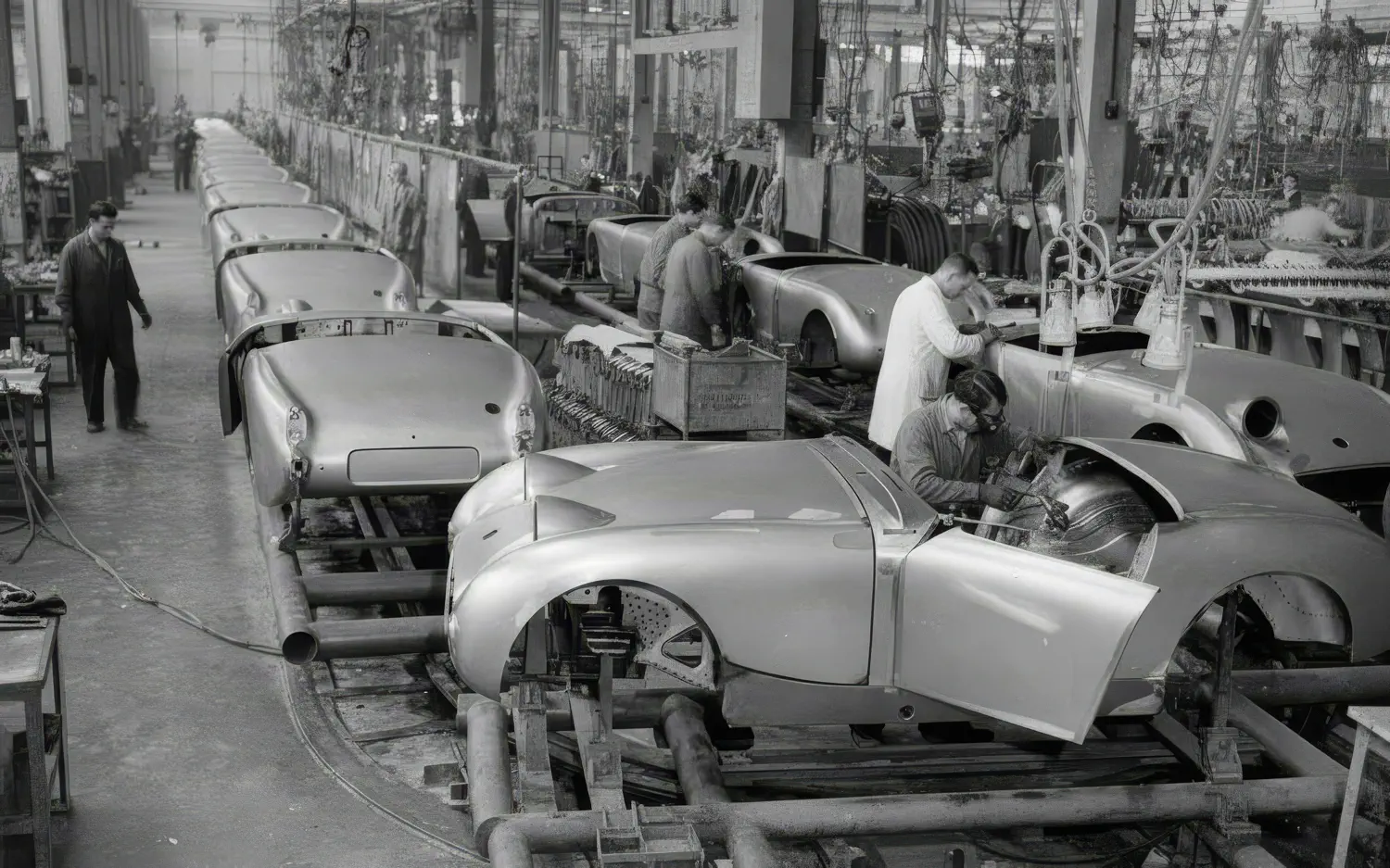

The Silent Partner

Once freed from Morris's control, Pressed Steel became something extraordinary: a company that effectively controlled the British motor industry without building a single complete car. By 1953, they ran over 350 power presses, some developing 1,000 tons of pressure, in a factory covering an area half the size of Hyde Park. Their mastery of deep-draw pressing created the flowing, curvaceous shapes that defined British cars of the era. The beautiful lines of a Jaguar Mark II existed only because Pressed Steel could stamp complex panels that smaller firms couldn't touch.

The list of manufacturers dependent on Cowley read like a social register of British motoring: Rolls-Royce and Bentley for the aristocracy, Jaguar for the successful, Rover for the respectable middle class, and the entire Rootes Group for everyone else. Austin, Daimler, Hillman, Humber, MG, Riley, Singer, Wolseley. If you wanted to launch a new car in Britain and were not Ford, you queued at Pressed Steel.

A Brief Diversion

Someone at Pressed Steel realised in 1934 that their enormous presses, designed for stamping car roofs, could just as easily stamp refrigerator panels. The Prestcold division was born, applying automotive production techniques to keep milk fresh. It was wonderfully pragmatic lateral thinking with an absurdist quality. The same factory that produced bodies for a Rolls-Royce one minute could manufacture the fridge your grocer used to store his butter the next.

During the Second World War, those massive presses were stamping components for Spitfires, shell casings, and millions of jerry cans. They factory kept the RAF flying and the Army supplied.

After the war, Prestcold became one of Britain's biggest refrigerator makers, winning design prizes and employing thousands in a new Welsh factory.

They also had a go at aircraft, which didn’t quite work out. In 1960, Pressed Steel backed Peter Masefield’s vision to build light aeroplanes through British Executive and General Aviation. They bought Auster and Miles to form Beagle Aircraft. The venture rested on the touching assumption that skill in stamping car doors automatically translated to building aeroplanes. It did not.

Wild production forecasts, chaotic management, and costly delays drained money at an impressive rate. By 1966, Pressed Steel had lost £3 million and begged the government to take Beagle off their hands. The experiment proved that metal pressing was not, in fact, a universal skill.

The Fatal Acquisition

On paper, it made perfect sense: British Motor Corporation secured its body supply and the world's largest independent body manufacturer in one move. Twelve months later, BMC bought Jaguar Cars, and formed British Motor Holdings.

The timing was not coincidental. William Lyons, Jaguar’s founder, had become a bit concerned when his main body supplier fell into the hands of his biggest competitor. Without assured access to Pressed Steel, Jaguar’s future didn’t look great.

For every other manufacturer relying on Cowley, the BMC takeover was catastrophic. Rover, Rootes Group, Rolls-Royce, and the rest suddenly found their body supplier owned by their primary rival. The paranoia was entirely justified. Nobody wanted to wait six months for bodies while BMC's orders jumped the queue. The situation forced nearly every independent British carmaker toward the same inevitable conclusion: merge or die. BMC had essentially weaponised the supply chain, and everyone else scrambled for cover.

In 1968, the government pushed BMH into Leyland's arms, creating British Leyland. The resulting chaos would become a case study in how not to run anything more complicated than a coffee shop. Pressed Steel Fisher, as it was now called, disappeared into this shambles. The puppet master had been absorbed by one of the puppets. The company that had once held every British carmaker hostage became just another failing division answering to committees.

What survives today are three factories: BMW builds Minis at Cowley, Swindon still stamps panels, and Castle Bromwich makes Jaguars. Not bad for a company born from an expensive divorce that went on to strangle an entire industry.