The Audacity Club

The first cars were rubbish. Noisy, unreliable, oily contraptions designed by madmen in sheds, and their main function was to catch fire or strand you in a ditch miles from civilisation. Most car companies, quite sensibly, spent their time trying to make them slightly less terrible. Ariel preferred to prove points by attempting something so spectacularly difficult and pointless that no sane person would even consider it.

The Hour

In the 1890s, Ariel was still making bicycles, and bicycle racing was professional sport at its finest. Huge crowds, serious money, and riders who trained like athletes. The one-hour record was cycling's ultimate test: how far could a human being pedal in 60 minutes?

J.W. Stocks was Ariel's factory rider, a professional who'd been racing since 1888. In 1897, he took to the Crystal Palace track with one goal: break every cycling record from one mile to one hour. For 60 minutes, Stocks pedalled without stopping, without coasting. Just sustained effort against the clock and his own limits. When the bell rang, he'd covered 32.75 miles. A world record, and genuinely impressive even by modern standards - the current record, set on a bike that resembles a spaceship, stands at just 35.29 miles.

Two years later, Stocks climbed onto an Ariel motor tricycle, one of the company's first experiments with internal combustion, and rode for 24 hours straight. Nobody had asked Ariel to prove a motor tricycle could survive a full day of continuous operation. They proved it anyway, with Stocks covering 434 miles. This established the pattern: build something, then find the most absurd way imaginable to prove it works.

The Mountain

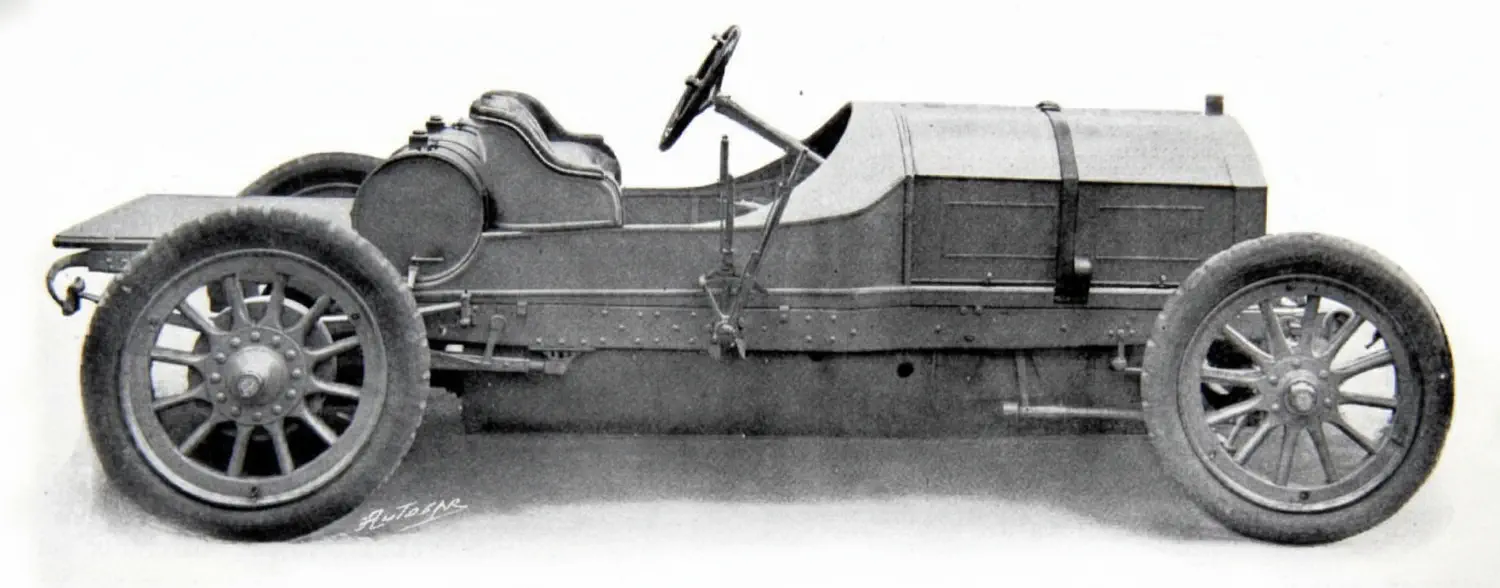

By 1904, Ariel had moved into car production and needed to prove their vehicles were more than expensive toys. Harvey Du Cros, working with the company, looked at Snowdon, the highest peak in Wales at 3,560 feet, and proposed driving up it.

There was no proper road. The plan involved using the mountain railway track, which meant driving on sleepers and ballast designed for trains, not wheels. The gradients on the railway reached 1 in 5 in places, steep enough that the car had to be coaxed and wrestled upward. The weather could turn vicious without warning. They'd be doing this in an Edwardian car with modest power and questionable brakes.

The first attempt ended in failure partway up. Most companies would have taken this as a sign that mountains were best left to mountaineers.

Du Cros came back later that year with Ariel's 15-horsepower car. The ascent took determination bordering on obsession. The car had to be manhandled up sections where the gradient made progress feel impossible, the wheels scrabbling for grip on greasy railway ballast never meant for road vehicles. When they finally reached the summit, they'd proven absolutely nothing of practical value. No customer would ever need to drive up Snowdon.

But as a statement of engineering arrogance it was magnificent. The newspapers loved it. Potential customers, most of whom would never encounter a gradient steeper than their local high street, were suitably impressed. Ariel had just invented the automotive publicity stunt.

The Wall of Death

Having conquered nature, Ariel went looking for man-made challenges. Brooklands, the world's first purpose-built motor racing circuit, opened in 1907. The concrete banking was so steep that drivers had to look up through the corners. At its steepest, you were driving on a wall tilted at 30 degrees. The centrifugal force at speed held you against the concrete, but if you slowed wrong, gravity would pull you sideways down the slope. The surface was rough enough to shake the car to pieces.

In 1907, cars had cart springs, solid axles, and the comfort of a metal bench. Drivers sat upright in the open air, wrestling huge steering wheels while the wind tried to pull them out. There were no seatbelts. If you crashed, you flew out and hoped for the best.

Ariel was on the starting line for the very first race on July 6, 1907. They came second, a spectacular result for a company that didn’t build racing cars. But second wasn't enough for Charles Sangster, the company's owner. Sangster believed the best way to sell cars was to personally demonstrate their superiority, preferably at terrifying speeds on concrete walls of death. He started entering races himself, actually driving the cars, risking machinery and neck to prove Ariel quality.

At the second Brooklands meeting, Sangster won his race.

The Miserable Holiday

By 1924, Ariel's cars had become more sophisticated but the appetite for punishment remained. The RAC Trial was designed to test reliability in the most comprehensive and miserable way possible. The route covered 1,788 miles from Land's End at the bottom of Cornwall to John O'Groats at the absolute end of Scotland, and back again.

The Ariel Ten saloon had weather protection that might charitably be described as optimistic. The roof kept some of the rain out, most of the time. The heating was whatever warmth happened to leak from the engine. The suspension was leaf springs and friction dampers, which meant every pothole went straight through the seat into your spine. The roads ranged from adequate to appalling.

To make matters worse, the rules forbade coasting downhill. Every mile had to be covered under power, a regulation seemingly designed purely to maximize fuel consumption and driver misery. You couldn't enjoy the rare pleasure of rolling down a hill in silence. You had to keep the engine engaged, burning fuel, making a lot of noise.

Donald Healey, then an Ariel dealer who would later become famous for Austin-Healey sports cars, took the wheel. For nearly 1,800 miles, the little Ariel kept going. It didn't break, didn't boil over, didn't give up. The car averaged 54 miles per gallon and used only five pints of water for the entire journey.

This was exactly what the trial was designed to prove: that a car could handle real-world conditions without constant mechanical attention. Customers in 1924 wanted to know if their purchase would get them to work and back without breaking down or bankrupting them. The RAC Trial proved, in the most tedious way possible, that an Ariel would. It was also, without question, the most miserable holiday anyone had ever been on.

The Motorcycle That Refused to Slow Down

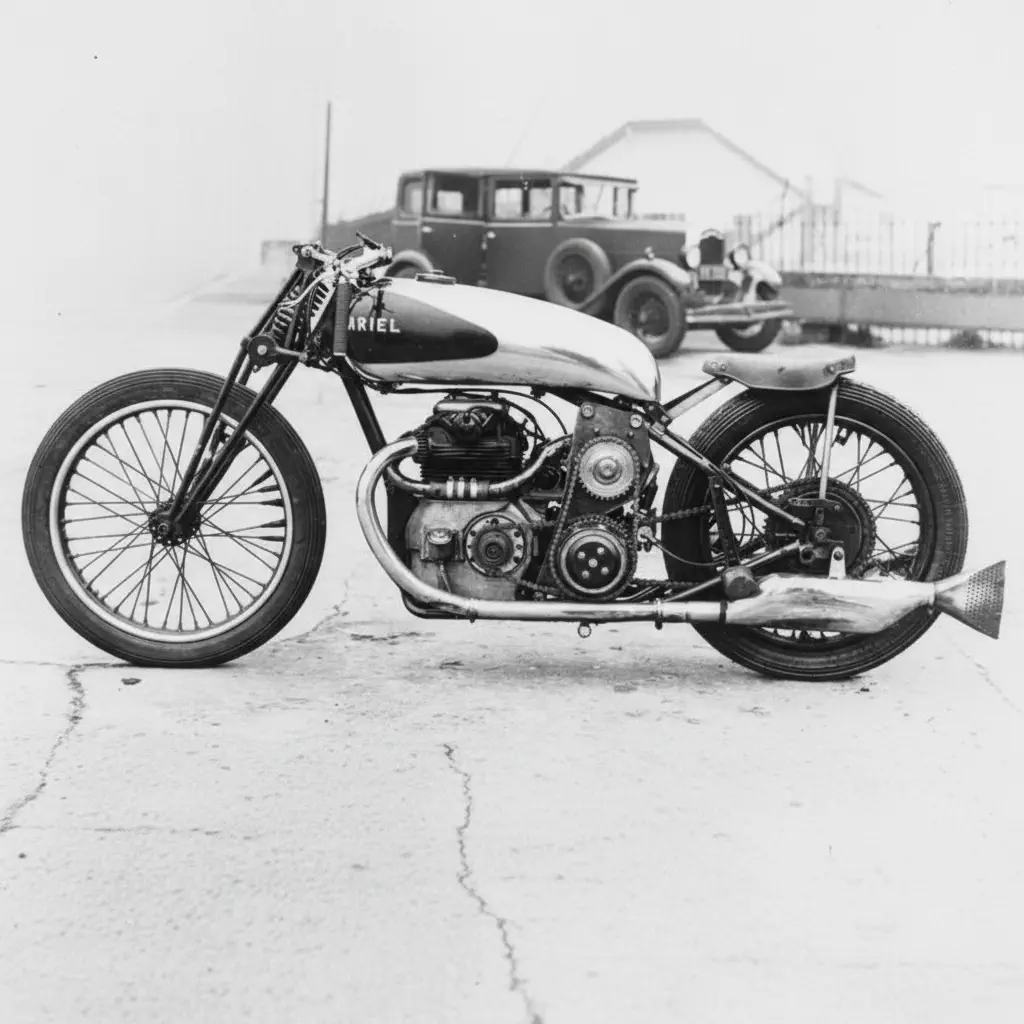

Ariel being Ariel, soon after, in 1925, they stopped making cars and committed to motorcycles. This turned out to be their most successful decision, though it followed the same pattern of proving things through difficulty. The Square Four, Edward Turner's masterpiece of complicated engineering, featured four cylinders arranged in a square, two crankshafts, chain-driven overhead camshafts. It was heavy, hot, and complex.

Ariel decided to strap a supercharger to it and see how fast it would go.

Ben Bickell took the supercharged Square Four back to Brooklands in 1933. The banking was still the same concrete wall of death, but now Bickell was on a motorcycle, which meant all those bumps went directly through his body without even the crude automobile springs to cushion them. The front wheel would skip across imperfections. The whole bike would shake. The wind would try to pull you off. All of this while leaning into a 30-degree banking with nothing between you and death except skill.

Bickell lapped at 110mph, setting a record that stood for years. The Square Four remained in production for nearly 30 years, but that 110mph lap was the defining moment. Proof that Ariel's approach produced machines capable of extraordinary performance, even when pushed far beyond their intended limits.

The Pattern Holds

From J.W. Stocks pedalling for 24 hours on a motor tricycle to Ben Bickell lapping Brooklands at 110mph on a supercharged Square Four, the pattern stayed consistent. Ariel built things, then found the most difficult possible way to prove they worked. Mountains without roads. Concrete banking that terrified professional drivers. Terrible weather for 1,800 miles. Twenty-four hours without stopping.

The company spent decades unable to decide if it was making bicycles, cars, or motorcycles. But it never wavered on one principle: if you build something, you prove it works by doing something absurd. Most companies talked about quality and reliability. Ariel preferred to climb Snowdon, then invite the newspapers to watch.