Ariel: The Company That Couldn't Make Up Its Mind

There's a particular kind of talented person who never quite succeeds because they can't commit to anything. They start training as a doctor, get bored, switch to architecture, show promise, then decide they'd rather be a concert pianist. They're brilliant at everything and successful at nothing. By the time they're fifty, they've accumulated three divorces, four abandoned degrees, five unfinished novels, and a garage full of half-completed projects. Everyone agrees they could have been extraordinary at any one thing. Instead, they're fascinating and broke. Ariel was the automotive equivalent of that person.

If you mention the name today, people think of the Atom, that mad-looking piece of scaffolding with a Honda engine that rearranged Jeremy Clarkson's face on television. But the modern Ariel Motor Company is a completely separate entity. The original Ariel was one of Britain's oldest vehicle manufacturers, and for thirty years it couldn't decide what it wanted to be. Bicycles? Motor cars? Motorcycles? It tried to be all three at once, achieved excellence at each, then moved on before anyone noticed.

The Wheel Deal

James Starley and William Hillman founded Ariel in Birmingham in 1870, making bicycles at a time when bicycles were gym equipment accidents waiting to happen. Starley introduced the "Ariel Ordinary", a penny-farthing with the first patented tensioned wire spoked wheel. Before this, wheels were heavy wooden affairs borrowed from carts. Starley's innovation made bicycles light enough to be practical transport rather than just dangerous entertainment for men with strong legs but poor judgement.

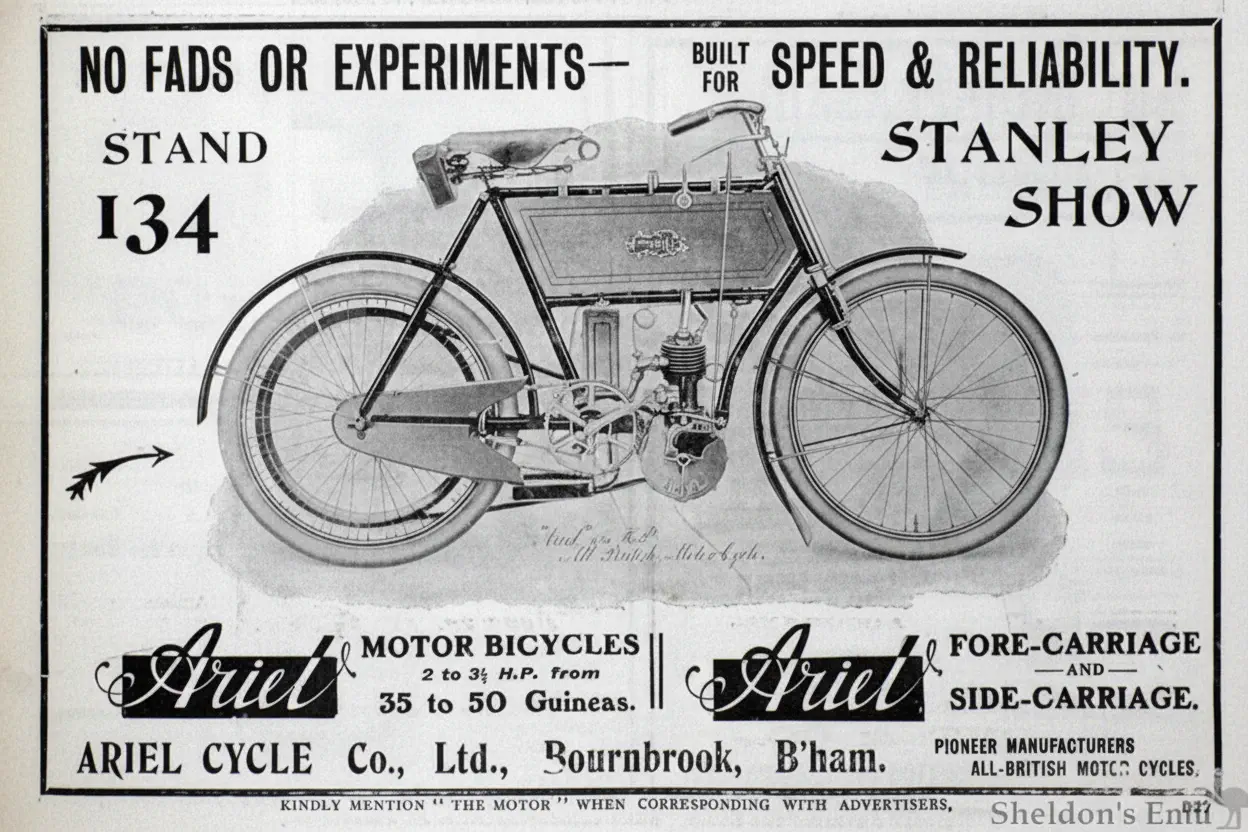

When the internal combustion engine arrived, Ariel strapped a 239cc De Dion engine to a tricycle and by 1902 had produced their first proper car. A robust 10hp twin-cylinder machine aimed squarely at the quality end of the market. The problem was immediately apparent: Ariel had Rolls-Royce ambitions but village blacksmith production capacity.

An Excess of Ambition

Ariel's Edwardian catalogue read like a technical wish list rather than a business plan. The experimental "Ariel Nine" with its horizontally-opposed twin-cylinder engine. Grand four-cylinder tourers. Pressed steel frames. Shaft drives when competitors were still relying on belts that snapped halfway up hills. The cars worked beautifully. Nobody bought them.

So Ariel doubled down on publicity. An Ariel became the first car to climb Mount Snowdon, which involved a sputtering Edwardian contraption clawing its way up a Welsh mountain while locals and sheep looked on with judgmental expressions. They took second place in the first-ever race at Brooklands in 1907. The bonnet straps used on that racing Ariel supposedly inspired the look that later became standard on Bentleys and Bugattis. Ariel accidentally influenced automotive design while failing to sell enough cars to pay the rent.

Between 1902 and 1916, they produced around 700 cars. Those are bankruptcy numbers, not dynasty numbers. But instead of admitting defeat, Ariel decided to try again after the war, because apparently once wasn't enough.

The Noble Failure

They emerged from the Great War in 1918 determined to re-enter the car market. This worked about as well as one would expect. By 1925, the company stopped making cars entirely. Ariel chose survival over status, which showed unusual pragmatism. It also showed that brilliant engineering means nothing if nobody can afford to buy it, a lesson many British marques would spend the next hundred years refusing to learn.

Two Wheels and Vindication

Jack Sangster saved Ariel by admitting the cars were a vanity project. He hired Val Page, who created the Red Hunter, the hot hatch of its day. One lapped Brooklands at over 101mph in 1939 to earn a coveted Gold Star, which for motorcyclists was basically a knighthood, minus the sword and the meeting with royalty.

The Square Four was something else entirely. Designed by Edward Turner and launched in 1931, it squeezed a four-cylinder car engine into a motorcycle frame by arranging the pistons in a square formation. It ran hot enough that prolonged riding left your trousers smelling vaguely of barbecue. But it was incredibly smooth, a gentleman's express that could cross continents with a distinct turbine-like whoosh. It saved the company during the Depression.

Vic Mole, the sales manager, organized ridiculous stunts including riding an Ariel across the English Channel and 10,000-mile non-stop endurance runs. Customers reasoned that if an Ariel could survive Vic Mole's abuse, it could probably handle the commute to Basingstoke without complaint.

Death by Committee

Sangster sold Ariel to the BSA group in 1951. They produced the Ariel Leader and Arrow, futuristic motorcycles that looked genuinely modern. The British motorcycling establishment immediately viewed them with deep suspicion. Anything that looked foreign or unconventional was clearly a threat to proper British values, even if it was designed in Birmingham.

Then the Japanese arrived with their reliable, oil-tight Hondas. The British industry responded with bad management, labor disputes, and a stubborn refusal to believe anyone could build motorcycles better than Britain. BSA rationalized its brands. Ariel was killed off.

The final vehicle to bear the Ariel name was the Ariel 3, launched in 1970. A tilting three-wheeled moped that combined the stability of a shopping trolley with a broken wheel, the performance of an asthmatic hamster, and the aesthetic appeal of a melted vacuum cleaner. It was unstable, ugly, and so embarrassingly awful that former Ariel employees reportedly refused to admit they'd worked there. The company that had climbed Mount Snowdon ended its life with a plastic tricycle that struggled to reach 30mph without falling over.

The Ghost That Wouldn't Die

The original Ariel had the talent to rival anyone but couldn't commit. Outstanding cars? Built them, abandoned them. Excellent motorcycles? Built them, found success, got killed off by corporate accountants. The pattern repeated itself: technical excellence, commercial confusion, move on before success solidifies.

Yet the name refused to stay dead. Decades later, the modern Ariel Motor Company resurrected the badge. The original Ariel started with bicycles, with exposed frames and obsessive attention to weight. The modern Ariel Atom is a high-tech bicycle frame with a car engine, returning to that Victorian philosophy of lightness and speed that Starley pioneered in 1870.

The original Ariel kept abandoning inspired ideas to chase different inspired ideas. They were brilliant at everything and successful at nothing long enough to matter. But sometimes the idea proves more durable than the execution. The modern Atom proves that Ariel's original instinct was right all along. The original company just couldn't focus long enough to prove it themselves. They were too busy being brilliant at something else.