Austin Healey: The Deal of the Century

Donald Healey had a gorgeous sports car and no way to build it in any real numbers. Leonard Lord had Britain's largest car factory and a warehouse full of parts from a saloon that Americans had looked at once and decided they'd rather walk. On the Thursday of the 1952 Earls Court Motor Show, these were two separate problems. By Saturday evening, they'd become one remarkably profitable solution. Lord walked onto Healey's stand, saw the crowds mobbing a prototype built from Austin bits, and made his mind up. Done. The car would be manufactured at Longbridge, carry both their names, and Healey would collect a royalty on every sale. The fundamentals were settled before the weekend ended. It was decisive rather than careful, instinctive rather than strategic, and it created one of the most successful partnerships in British motoring history.

The Rally Champion's Dilemma

Donald Mitchell Healey had won the Monte Carlo Rally in 1931, served as Triumph's engineering director before the war, and afterwards set up in Warwick building sports cars with Riley engines. They handled beautifully and went properly quickly. Cost £1,500 each, though. At that price, customers wanted established names, not a workshop in the Midlands they'd never heard of. Healey was shifting dozens when he needed hundreds.

He needed something simpler and considerably cheaper. A manufacturing partner with actual factory space would help, given his operation couldn't scale beyond tiny production runs. Most importantly, he needed parts that someone else was already making, because funding new tooling would bankrupt him before he'd manufacture a single car.

Austin's parts catalogue provided the answer. The A90 Atlantic was a saloon Austin had designed for America, apparently believing Americans wanted heavy British cars with peculiar styling. Americans disagreed, leaving Austin with warehouses full of unwanted bits. The 2.6-litre four-cylinder was rough and the car graceless, but the mechanical elements were robust. More to the point, Austin would sell them very cheaply just to clear inventory.

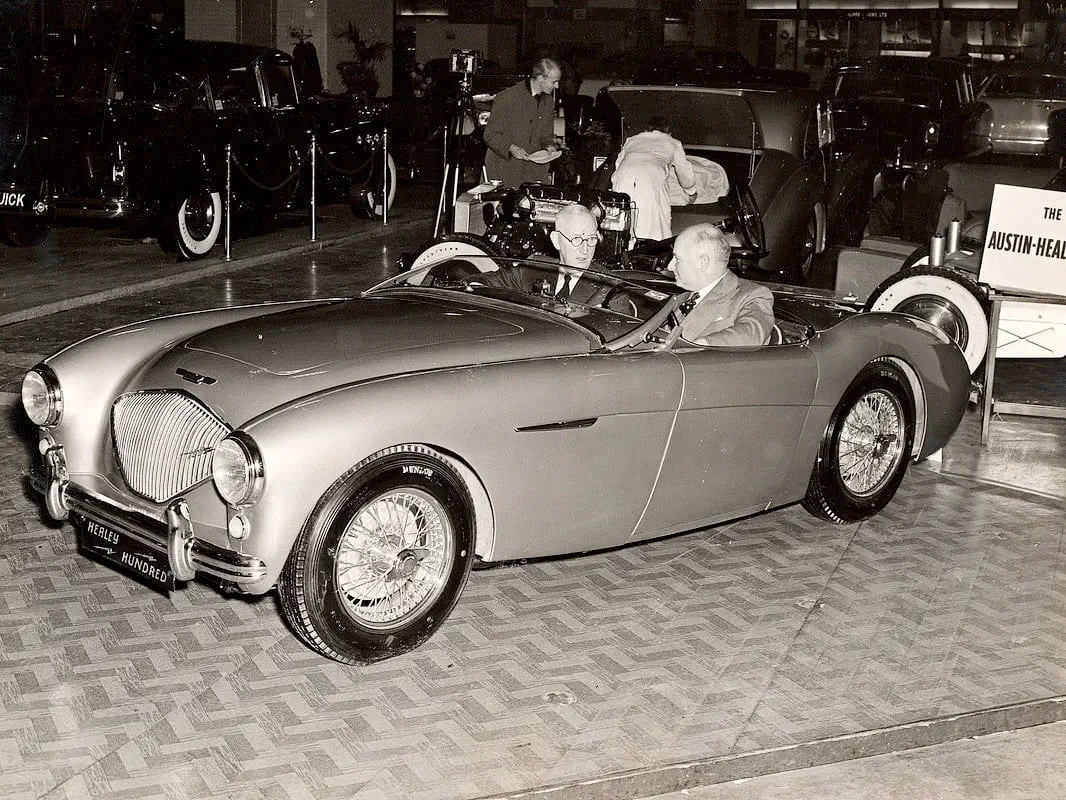

Healey took a set back to Warwick and designed a body that would make people forget they were looking at saloon castoffs. What emerged was startling. Low, flowing, perfectly proportioned. It looked expensive and Italian rather than cheap and British. He called it the "Healey Hundred" for its claimed 100 mph capability, and whether this was accurate mattered less than the fact it sounded ambitious and looked fast standing still. This was what he took to Earls Court, hoping for enough orders to justify building a few hundred. The crowds suggested he'd been conservative.

The Chairman's Decision

Leonard Lord hadn't reached Austin's chairmanship by waiting for other people's opinions. He'd worked his way up through bloody-mindedness, considerable engineering talent, and a temper that made anyone think twice before disagreeing. He ran Austin personally, making calls based on what he could see rather than what planning departments thought might be advisable in eighteen months.

When he visited Healey's stand, he found it mobbed. People were genuinely excited about this beautiful sports car from a manufacturer nobody knew, built entirely from Austin saloon parts. Lord grasped it immediately. Here was a solution: what to do with those unsold Atlantic bits and how to enter the sports car market without development costs.

Austin would manufacture it at Longbridge. Both names on the badges. Healey gets royalties. According to legend, this was settled before the show closed, though reality probably involved a few more meetings. Even so, it was swift by any normal standard.

The Austin-Healey 100 that entered production in 1953 cost £750, half what Healey had charged before. You got a proper sports car with a fold-down windscreen, weather protection that worked better in theory, and a character built for driving rather than pampering. Heavy steering, firm ride, gear lever that needed commitment. Americans loved it.

It looked European and exotic but had an engine any American mechanic could service with standard tools and profanity. No mysterious Italian electrics, no complex German engineering requiring specialists. When it went wrong, you could fix it yourself or take it to the nearest garage. Within months, most production was heading to the United States.

Thunder and Victory

The four-cylinder was willing but coarse, sounding like farm equipment rather than sport. American customers wanted more power. Austin's response was typically direct: they bolted in the 2.6-litre straight-six from their Westminster saloon. No lengthy development, no years of testing. Just swap the engine. The result was the 100-6, which evolved into the 3000, and that was when the Big Healey stopped being merely quick and became something you had to respect.

With around 150 horsepower driving the rear wheels, the 3000 was rapid by late 1950s standards. But what made it memorable was the character in industrial quantities. Steering heavy enough that parking required planning. Cockpit that heated your feet uncomfortably. The whole machine felt perpetually on the edge of doing something dramatic. The exhaust note was magnificent, a deep rolling thunder wildly disproportionate to the car's size.

The factory rally team proved that sophisticated engineering wasn't always necessary to win. Pat Moss and Paddy Hopkirk campaigned the 3000s with ferocious success across Europe, sliding them through Alpine passes in clouds of tyre smoke while the exhausts crackled. They won rallies and races, proving you didn't need Italian sophistication or German precision. Just a tough car and a driver who knew their business.

The rally victories made headlines, but the real triumph was commercial. Thousands of Americans bought Big Healeys, drawn by handsome looks, thunderous performance, and mechanical honesty. It became the archetypal British sports car: valuing character over sophistication and making no apologies for it.

The Cheerful Frog

While the Big Healey was winning rallies, Healey spotted another gap. Sports cars existed for people with money, but what about those who worked for a living? The schoolteacher, the junior manager, the young engineer with a few hundred pounds? In 1958, Austin-Healey gave them the Sprite, possibly the most ruthlessly efficient cost engineering the British motor industry ever achieved.

Every part came from the Austin A35 saloon. Same 948cc engine, same gearbox, same suspension. Nothing required fresh tooling. The body was tiny and simple. Doors had no exterior handles because handles cost money, so you opened them from inside. No boot lid either. And instead of expensive pop-up headlights, they mounted them in fixed pods on the bonnet, giving the car a face like a very surprised frog.

The nickname "Frogeye" appeared within days and stuck permanently. It resembled a startled amphibian but also looked absurdly happy, as if designed to cheer everyone up. That gormless expression became its greatest asset. While other sports cars looked serious and expensive, the Sprite looked like it was having the time of its life.

At £669, it made sports car ownership possible for people who'd never imagined affording one. When you drove a Sprite, with its engine revving enthusiastically and weighing barely more than a large motorcycle, you discovered that enjoyment doesn't come from horsepower. Light weight and eager responses. That's what matters. The heater produced more noise than warmth, weather protection kept out light drizzle at best. None of this mattered because it delivered joy in its purest form, and did so with such obvious cheerfulness that people adored it precisely because it looked ridiculous.

When Committees Take Charge

Over two decades, Austin-Healey sold more than 200,000 cars, most exported to America. Successful by any measurement. But the British motor industry spent the 1960s reorganising with enthusiasm that usually ends badly. BMC merged with Jaguar, absorbed Pressed Steel, then became British Leyland, a sprawling conglomerate seemingly determined to make every decision by committee.

In 1967, British Leyland examined their sports car portfolio and concluded they had too many brands. Austin-Healey, MG, and Triumph all made sports cars, which on organisational charts looked like duplication. The solution was to eliminate one. They chose Austin-Healey. Donald Healey had designed a modern replacement called the 4000. Cancelled. The Big Healey itself was discontinued. Years later, the Sprite followed.

The decision made perfect sense if you were looking at charts and believed fewer brands meant efficiency. It made less sense if you understood that each brand had its own customers who'd been buying them for twenty years. But corporate logic insisted duplication was wasteful, so one of Britain's most successful automotive exports was eliminated to tidy a spreadsheet.

Leonard Lord had created the partnership by walking onto a stand at Earls Court, seeing what was there, and deciding before the weekend ended. Quick judgement. The cars that resulted sold worldwide and brought in millions. The partnership ended when people who'd never met Healey, never drove a Big Healey, and possibly never understood why anyone would want a sports car, decided it was inefficient after careful analysis. They were probably very thorough. They certainly had reports. And they were completely wrong. Sometimes the snap judgement works better than the committee report. The Austin-Healey story proved it. The people who ended it never learned it.