Bond Cars: Wizards of the Wobbly Wheel

The British have always possessed a genius for spotting loopholes, particularly when they involve outwitting the taxman while maintaining a veneer of respectability. And there has never been a more glorious, more precarious, or more thoroughly British automotive loophole than the three-wheeler. For nearly two decades, the undisputed master of this peculiar kingdom was Bond, a company that transformed the art of building cars that legally weren't cars into a thriving business serving people who wanted motoring freedom without paying for the privilege of that fourth wheel.

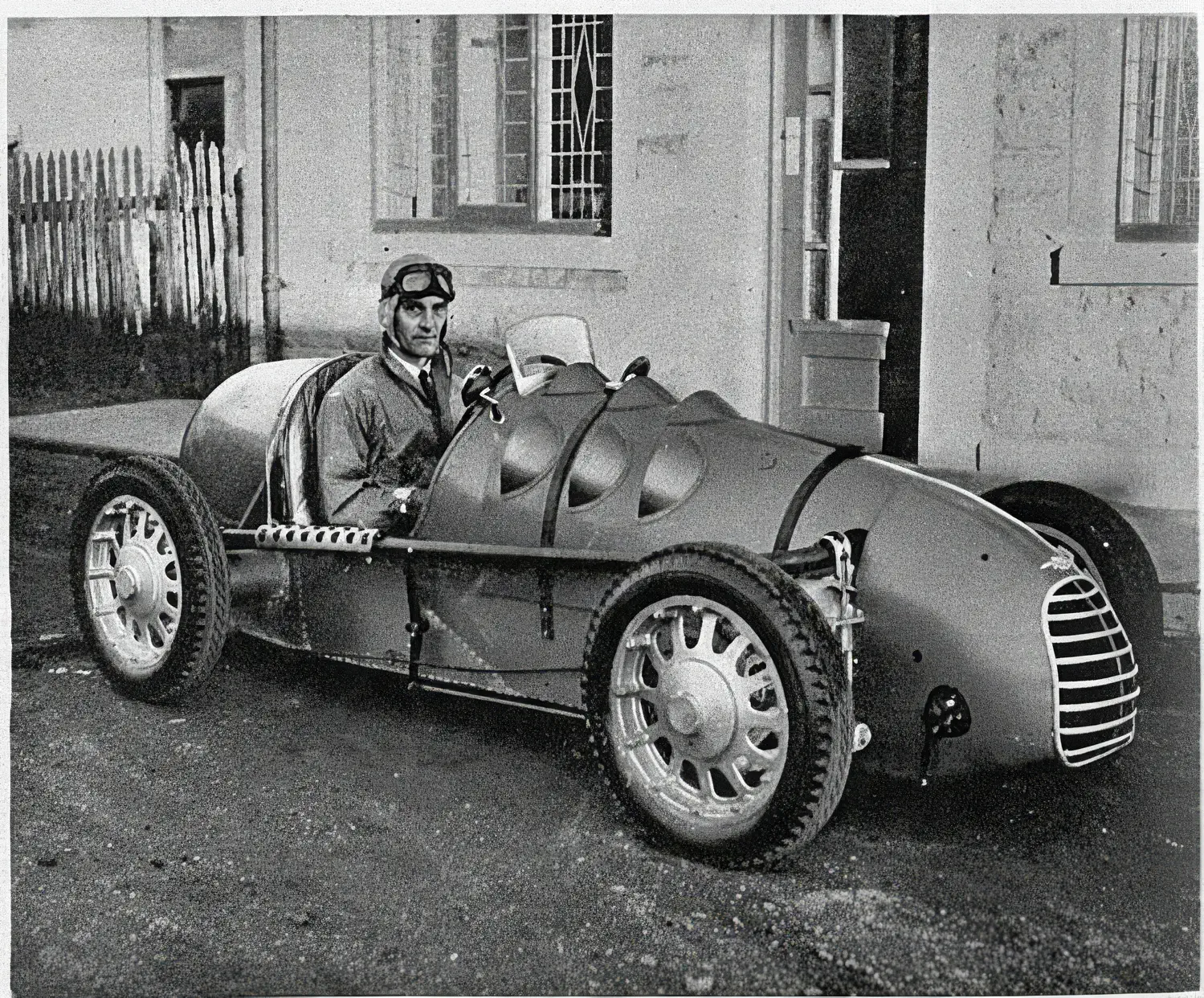

The Aeronautical Minimalist

The Bond story begins with Lawrence "Lawrie" Bond, a brilliant aeronautical engineer whose wartime experience designing aircraft for Blackburn led him to a radical conclusion about road transport. Having spent the war years perfecting the art of making things lighter, stronger, and more efficient for flight, Bond saw the conventional four-wheeled car as a monument to waste. Why drag around unnecessary weight, complexity, and expense when clever engineering could deliver the same result with less?

In early 1948, Bond revealed his prototype to the press: a "short radius runabout for shopping and calls within a 20-30 mile radius." The demonstration was telling. His creation climbed a twenty-five percent gradient with driver and passenger aboard, achieved a remarkable 100 miles per gallon, and could reach thirty miles per hour. But the real genius lay not in what it did, but in what it avoided doing. With no reverse gear, minimal weight, and only three wheels, it qualified for motorcycle taxation and licensing. Bond had spotted the perfect regulatory gap.

The Preston Revolution

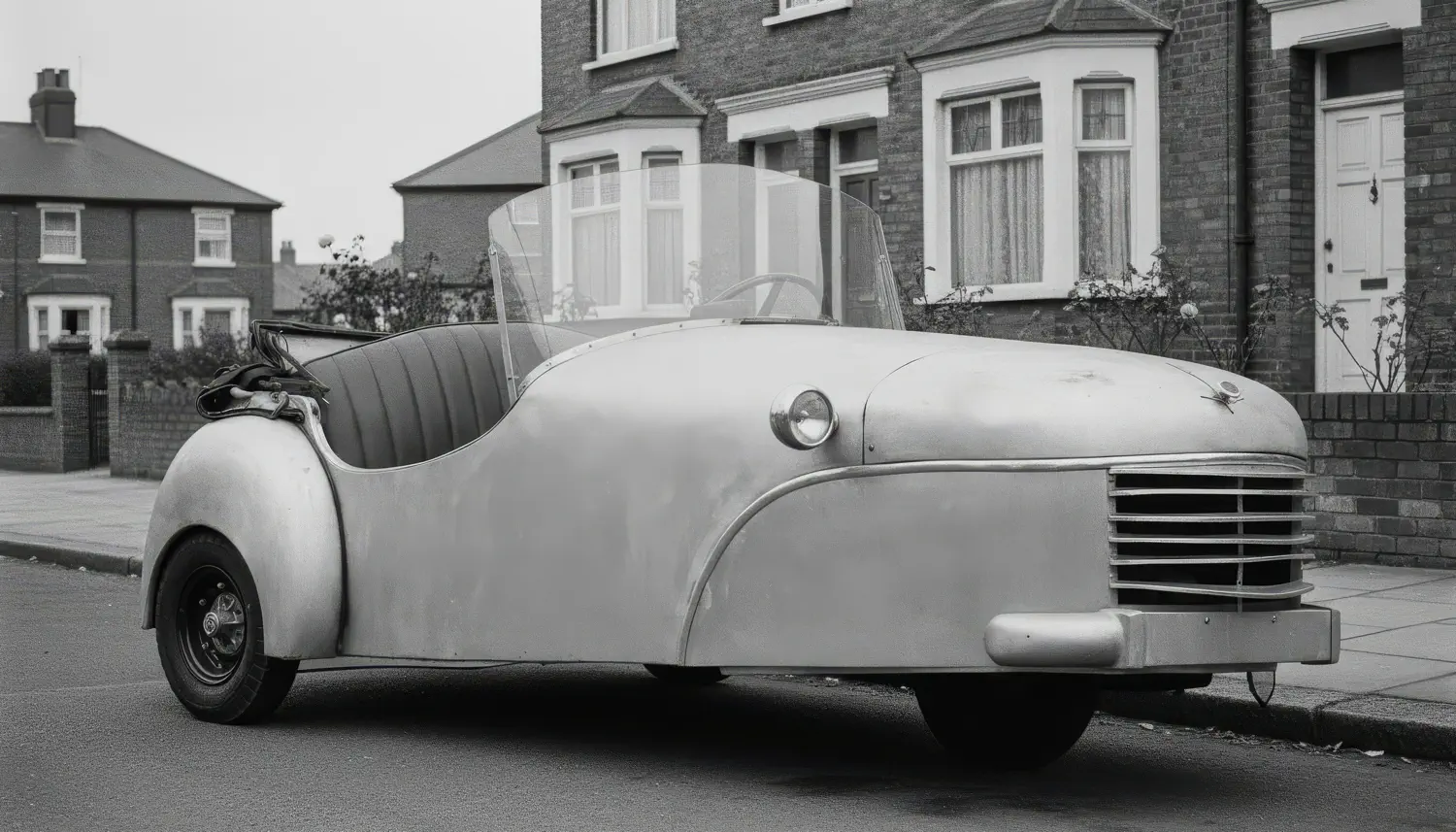

Production began in January 1949 at Sharp's Commercials in Preston, run by the pragmatic Colonel Charles Reginald Gray. The original Mark A Minicar was austere to the point of comedy: aluminium stressed-skin construction, a 122cc Villiers motorcycle engine started with a pull handle under the dashboard, and cable-and-bobbin steering that connected the wheel to the front assembly through a system of pulleys. You entered by climbing over the sides, as doors were an unnecessary luxury.

Yet this stripped-down machine delivered exactly what post-war Britain needed. At £262 including taxes, it cost substantially less than any four-wheeled alternative. More importantly, it could be driven on a motorcycle licence, required minimal insurance, and paid motorcycle rates for road tax - a saving of £55 annually compared to conventional cars. For a generation emerging from rationing and austerity, the Minicar represented affordable independence. The company sold 1,973 Mark A models before introducing the improved Mark B in July 1951.

The Perfect Machine for Imperfect Times

The Minicar's genius lay in its complete adaptation to British regulatory peculiarities. The absence of reverse gear wasn't a limitation but a legal necessity - adding one would have reclassified it as a car, destroying the tax advantages. Instead, Bond's engineers made the entire front wheel assembly turnable through ninety degrees in either direction, allowing the car to pivot within its own length. Later models offered a sort of reverse through the ingenious Siba Dynastart system, which could run the engine backwards by reversing the starting motor.

This wasn't just clever engineering; it was brilliant social positioning. Driving a Bond Minicar made a statement about your priorities. You were either magnificently frugal, genuinely impoverished, or possessed of an eccentric independence that simply didn't care what the neighbours thought. The Motor magazine recorded forty-three miles per hour flat out and seventy-two miles per gallon in normal use. For many buyers, that was perfection.

The Four-Wheeled Heresy

Having conquered the minimalist market with 24,482 Minicars sold by 1966, Bond committed what purists considered automotive sacrilege: they built a proper four-wheeled sports car. The 1963 Bond Equipe GT represented a complete philosophical reversal. Taking a Triumph Herald chassis, they clothed it in a genuinely beautiful fibreglass fastback body and fitted the lively 1147cc Spitfire engine.

The Equipe was everything the Minicar wasn't - sophisticated, quick, and utterly conventional in its pursuit of respectability. It proved Bond could play in the traditional sports car market, offering Triumph performance with distinctive styling at competitive prices. The car evolved through several iterations, gaining four seats with the GT4S and eventually the six-cylinder Triumph Vitesse engine in the 2-litre model. It was handsome, fast, and successful, but it also represented Bond's abandonment of everything that made them unique.

The Death of Distinction

By 1962, the British government had signed Bond's death warrant. Chancellor Reginald Maudling reduced purchase tax on cars from fifty-five percent to twenty-five percent, suddenly making four-wheelers competitively priced against their wobbly rivals. When your entire business model depends on regulatory arbitrage, changes in regulation prove fatal. Tom Gratrix, head of Sharp's, sent a desperate telegram to the Chancellor warning of 300 redundancies unless similar cuts applied to three-wheelers. The plea was ignored.

The timing couldn't have been worse. Alec Issigonis's Mini had arrived in 1959, offering genuine four-wheeled motoring at barely more cost than a Minicar. The sophisticated, economical, and infinitely more practical Mini made Bond's offering look suddenly archaic. Sales collapsed. In 1969, Reliant Motor Company acquired Bond Cars for a strategic reason that had nothing to do with expansion: elimination of competition. They wanted the Bond badge for their own ambitious project.

The Final, Magnificent Madness

Under Reliant ownership, Bond produced their most famous and most preposterous creation. In 1970, they launched the Bond Bug - a lurid orange, doorstop-shaped wedge designed by Tom Karen of Ogle Design. It possessed all the practicality of a fighter jet. Entry was via a massive lift-up canopy that incorporated windscreen, roof, and windows into one dramatic gesture.

The Bug was powered by Reliant's 700cc four-cylinder engine and could achieve seventy-six miles per hour - faster than the national speed limit. It cost £629, just £9 more than a basic Mini, but offered half the seats and a fraction of the practicality. Only 2,270 were built between 1970 and 1974, with virtually all finished in that arresting tangerine orange. Six were painted white for Rothmans cigarette advertising, making them among the rarest production cars ever built. The Bug represented everything wonderful and terrible about the British motor industry: brilliant design, questionable commercial logic, and absolute commitment to being different.

Legacy of Inspired Eccentricity

Bond Cars represented British automotive ingenuity at its most characteristically perverse. They built an entire business around a regulatory anomaly, then thrived by making that anomaly into something approaching art. The Minicar offered genuine transport for those who couldn't afford anything better, while the Bug provided pure automotive joy for those who didn't want anything normal.

Their story reveals the genius of British engineering: the ability to find profit in the gaps between regulations, purpose in apparent limitations, and success in serving markets nobody else wanted. Bond never pretended to build the best cars, but for eighteen remarkable years, they built exactly the right cars for their particular moment. When that moment passed, they had the grace to depart with one final, orange, and utterly magnificent flourish.