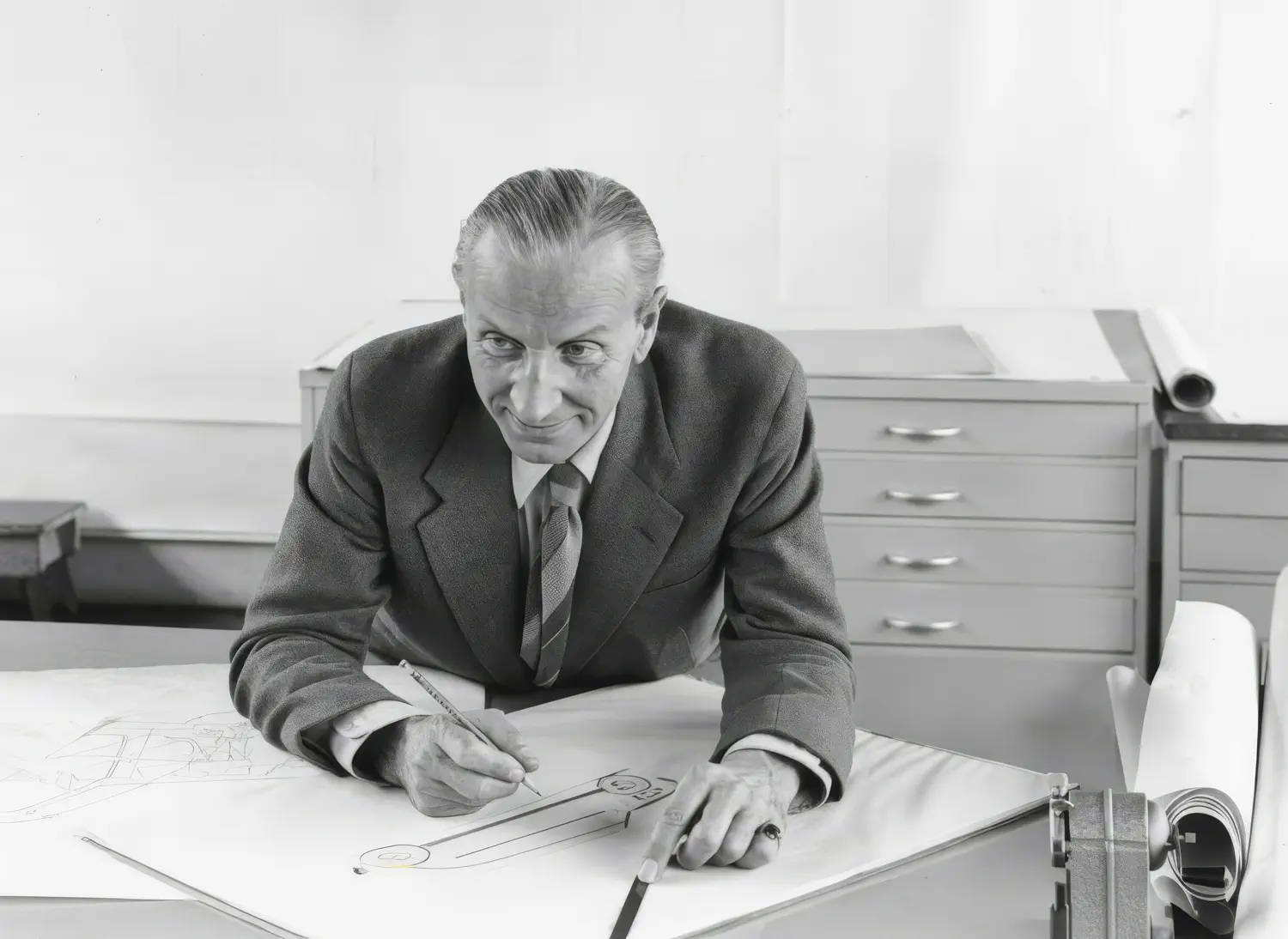

Alec Issigonis: The Genius Who Hated Empty Space

Alec Issigonis hated waste. Not the bins-out-on-Thursday kind, but the automotive sort: wasted space, wasted metal, wasted opportunity. While his contemporaries at Ford and Vauxhall obsessed over chrome and fins, Issigonis conducted a private war against empty air, treating unused cubic inches as a personal affront. This obsession with packaging efficiency made him one of the most influential British car designers of the twentieth century. It also made him insufferable to work with, nearly bankrupted his employers, and created cars that were simultaneously brilliant and commercially catastrophic.

Born on 18 November 1906 in the Ottoman port of Smyrna, Alexander Arnold Constantine Issigonis was born into a world of comfortable privilege. His grandfather Demosthenis had emigrated from the Greek island of Paros in the 1830s, built a successful engineering company working on British railway projects, and secured British citizenship for his descendants. His son Constantine became a prosperous marine engineer, marrying Hulda Prokopp from a Bavarian brewing family. Young Alec grew up speaking Greek and German in a grand house overlooking the Mediterranean, surrounded by servants and European culture. Then history intervened with typical Balkan brutality.

The Orphaned Engineer

The Greco-Turkish War of 1922 shattered this genteel existence. In September, as Turkish forces closed on Smyrna, the Royal Navy evacuated British subjects to Malta. Constantine Issigonis, already gravely ill, died there in June 1923. His sixteen-year-old son and widow moved to London with little beyond their British passports and fading memories of wealth. Hulda returned briefly to Malta for her husband's funeral, leaving Alec alone in London to navigate boarding school and an unfamiliar country.

At Battersea Polytechnic, Issigonis studied mechanical engineering with notable lack of success. He failed his mathematics examinations three times, subsequently declaring pure mathematics "the enemy of every truly creative man." This wasn't false modesty or charming self-deprecation. He genuinely believed that abstract thinking divorced from physical reality produced rubbish cars. He finally scraped a diploma in 1928 and entered an industry where engineering jobs were scarce and family connections non-existent.

His early career meandered. He worked as a draughtsman and salesman for an automatic transmission company, raced a supercharged Austin Seven he'd modified himself, and in 1936 finally landed a proper job at Morris Motors as a suspension engineer. The racing proved useful. His homebuilt 1939 special, constructed from plywood laminated in aluminium with suspension using rubber springs made from catapult elastic, weighed just 587 pounds and usually won its class. This demonstrated two characteristics that would define his career: lateral thinking about engineering problems and complete indifference to conventional solutions.

The Minor Masterpiece

During the war, Issigonis began work on an advanced small car codenamed Mosquito. Legend insisted that William Morris wasn't informed because management feared he'd object to wartime resources being diverted and recoil at Issigonis's radical ideas. The original design featured independent suspension all round and a new flat-four engine. When finally revealed, Nuffield was indeed horrified. The engineering was too expensive, the styling too peculiar.

Forced to compromise, Issigonis lost his flat-four engine and independent rear suspension. He struck back by insisting, at a dangerously late stage, that the entire car be widened by four inches to improve interior space and proportions. The result, launched in 1948 as the Morris Minor, became a phenomenon. It featured proper rack-and-pinion steering when rivals still used recirculating ball systems, and handled with a precision that made contemporary saloons feel agricultural. Over 1.6 million were eventually sold, making it the first British car to exceed one million production.

What made the Minor remarkable wasn't just the engineering. It was the philosophy: design from the inside out, prioritise the occupants, make every component earn its keep. This was Issigonis's manifesto, and he would spend the rest of his career perfecting it to increasingly expensive extremes.

The Packaging Zealot Ascendant

When Morris merged with Austin to form BMC in 1952, Issigonis resigned. He feared the large organisation would curb his freedom, which showed impressive self-awareness given that freedom was precisely what made him dangerous. He moved to Alvis, a small luxury car maker, where he designed an advanced saloon featuring an all-aluminium 3.5-litre V8, complex interconnected suspension developed with Alex Moulton, and a transmission system incorporating two gearboxes and two clutches. It would have bankrupted Alvis. The project was cancelled in 1955, and Issigonis was let go.

BMC Chairman Leonard Lord retrieved him, setting him to work on a new model range. The 1956 Suez Crisis changed everything. Fuel rationing loomed, and Lord ordered Issigonis to create a tiny, genuinely efficient car immediately. The legend holds that Issigonis sketched the basic concept on a napkin. The brilliance was simple: turn the engine sideways, drive the front wheels, mount the gearbox underneath in the sump, push ten-inch wheels to the absolute corners, and dedicate 80 per cent of the footprint to people and luggage.

The Mini, launched in 1959, was a packaging miracle. A car just ten feet long that seated four adults comfortably. It handled like a go-kart and reinvented what a small car could be. Issigonis gave it sliding windows because wind-up mechanisms were heavy, complex rubbish. He despised car radios as frivolous distractions. The Mini sold 5.3 million examples and influenced virtually every small front-drive car built since. There was one problem: BMC lost approximately thirty pounds on every base model sold. Ford bought one, stripped it to components, calculated the costs, and informed BMC they were haemorrhaging money. BMC had priced the basic Mini at £496 to undercut the Ford Anglia, but it lacked heaters, carpets, and opening rear windows. Even in this austere form, it was superior to rivals and far cheaper. Customers bought basic Minis in quantities BMC never anticipated, turning a bestseller into a financial disaster.

Issigonis immediately applied his formula to a larger family car. The ADO16, launched in 1962 as the Morris 1100, featured the transverse engine layout plus Moulton's sophisticated Hydrolastic suspension. Pininfarina styled it after Issigonis admitted, "I couldn't get it right." The 1100 became Britain's bestselling car for most of the 1960s, selling 2.1 million examples. At its peak, it held 15 per cent of the new car market. It was genuinely advanced, offering ride quality and space efficiency that shamed conventional rivals. It also featured the uncomfortable driving position that Issigonis apparently believed kept drivers alert through induced backache.

The Emperor's Expensive Clothes

Success bred hubris. Issigonis's next project, the Austin 1800 nicknamed the Landcrab, demonstrated both his genius and his dangerous detachment from commercial reality. Launched in October 1964, it offered astonishing interior space within a package shorter than a Ford Cortina. It won Car of the Year 1965. It also featured an umbrella-handle handbrake under the dashboard, a bus-like driving position, and cost £150 more than the Cortina while competing in the wrong market segment. BMC anticipated sales rivalling the 1100. They sold roughly 35,000 annually over eleven years, producing 386,000 total. The engineering was brilliant. The business case was catastrophic.

Issigonis reportedly considered the 1800 his favourite creation, which tells you everything about his priorities. He was a packaging zealot designing cars for an ideal world where customers cared only about space efficiency and ignored styling, ergonomics, or whether the damn thing made financial sense. BMC's management, dazzled by the Mini's cultural impact, kept giving him free rein. The company was probably losing money on every car it sold, a situation one can regard as either visionary or suicidal depending on one's tolerance for red ink.

His final project was the Austin Maxi, launched in 1969 as British Leyland's first new product. It was Britain's first five-door, five-speed hatchback. It featured doors from the 1800 because accountants demanded parts-sharing, compromising the styling. The cable-operated gearshift felt like mixing concrete with a wooden spoon. The 1485cc engine was gutless. Lord Stokes nearly cancelled the launch and brought in Harry Webster from Triumph to fix things, effectively pushing Issigonis aside. The Maxi sold about 472,000 over twelve years, respectable but disappointing given the ambition.

By then, British Leyland's management had learned an expensive lesson: letting Issigonis design cars without commercial constraints produced cultural icons that destroyed shareholder value. In 1971, he was moved to a "Special Developments Director" role, which meant exile to the margins while Ford-trained executives tried to save what remained of Britain's indigenous motor industry.

The Stubborn Architect's Contradictions

Issigonis retired officially in 1971, though he remained tangentially involved with BMC until his death. He was knighted in 1969, appointed FRS in 1967, made a CBE in 1964. The establishment recognised his achievements even as his employers counted the costs. He lived his final years in a bungalow in Edgbaston, tinkering with miniature steam engines in his garage, a man who loathed the twentieth century's latter half while inadvertently shaping its automotive landscape.

He died on 2 October 1988, aged 81. The obituaries celebrated his genius, which was authentic. They paid less attention to his character, which was impossible. Colleagues described him as autocratic, imperious, and intolerant of compromise. He believed the public didn't know what it wanted, and his job was to tell them. He dismissed market research as "bunk." He built deliberately uncomfortable seating because he thought backache kept drivers alert. When asked why the Maxi lacked styling appeal, he showed no interest in the question.

What made Issigonis significant wasn't just the Mini or the 1100. It was his demonstration that British engineering could equal or surpass anything from Detroit or Stuttgart when freed from financial discipline. Every front-drive small car built since 1960 owes something to his work. He proved that packaging efficiency and space utilisation mattered as much as horsepower or styling. He showed that small cars needn't feel compromised.

He also demonstrated why brilliant engineers shouldn't run car companies. His cars were too expensive to build, too peculiar for mass appeal, and designed with magnificent indifference to whether anyone could make money from them. BMC's decline can't be blamed entirely on one stubborn Greek mathematician who hated empty space, but his contribution was substantial. His distant cousin Bernd Pischetsrieder later steered BMW's disastrous Rover acquisition, suggesting that ignoring financial reality might have run in the family.

Issigonis remains the perfect embodiment of post-war British industrial ambition: technically brilliant, commercially naive, culturally significant, and ultimately unable to prevent the empire's dissolution. His cars outsold their rivals while bankrupting their manufacturer. They won design awards while losing money on every sale. They revolutionised automotive packaging while teaching accountants that revolution without profit is just expensive noise. He was a genius, certainly. Whether genius justifies ignoring balance sheets is a question British Leyland's creditors answered definitively, though perhaps not in the way Issigonis would have preferred.