Lawrence "Lawrie" Bond: The Engineer Who Started the Weight Revolution

Long before Colin Chapman made "adding lightness" the most famous phrase in motorsport, an aircraft engineer in Lancashire was already demonstrating that cars could be built like aeroplanes rather than steam engines. Lawrence "Lawrie" Bond spent the late 1940s constructing racing cars and road vehicles using stressed-skin techniques that wouldn't reach mainstream automotive engineering for another decade. His workshop in Longridge produced Britain's first monocoque microcar while Chapman was still at university. Today, even Chapman experts admit Bond may have blazed the trail that Lotus would follow - making his obscurity all the more remarkable.

The Perfectionist's Son

Most engineers eventually learn to accept that good enough is good enough. Laurie Bond never received that memo. Born on August 2, 1907, in Preston, to Frederick Charles Bond, a local historian and artist who believed there was always a more elegant solution to any problem, young Laurie inherited a dangerous combination of perfectionism and impatience with convention. After Preston Grammar School, he served his apprenticeship at Atkinson & Co., where they built steam wagons exactly as their grandfathers had - heavy, robust, and utterly unimaginative.

Bond watched his colleagues adding metal wherever they encountered a problem and wondered if they'd completely missed the point. Why use three components when one clever piece would do the job better? Why build something to survive the apocalypse when making it lighter would improve everything that actually mattered? At Henry Meadows, his colleagues in the drawing office thought him slightly unhinged as he constantly questioned why gearboxes needed to weigh quite so much. The move to Blackburn Aircraft was a revelation: suddenly Bond was working with engineers who understood that survival depended on making things lighter, not heavier. Every rivet counted, every ounce mattered, and anyone who suggested adding more metal was probably trying to kill you.

Wartime Lessons in Survival

From 1939, Bond found himself chief engineer at an aero components factory, spending the war years perfecting techniques that kept RAF pilots alive. While his automotive contemporaries maintained lorries and fixed staff cars, Bond was learning that the Germans had a nasty habit of shooting at anything that flew too slowly or carried too much weight. There was no room for the sort of cautious over-engineering that characterised British car manufacturing, where adding another chunk of steel was always considered the sensible solution.

Bond absorbed lessons that would take automotive engineers another twenty years to discover. Stressed-skin construction wasn't just lighter than conventional chassis - it was demonstrably stronger. Monocoque shells could do the work of separate frames while weighing half as much. Materials like aluminium weren't exotic experimental substances - they were logical choices for anyone serious about efficiency. In 1944, with victory approaching, Bond established the Bond Aircraft & Engineering Company in Longridge. When peace arrived and government contracts ended, most aviation suppliers simply shut their doors and looked for sensible jobs. Bond saw an opportunity that his competitors had missed entirely: why not build cars the way they built aeroplanes?

The Racing Revolutionary

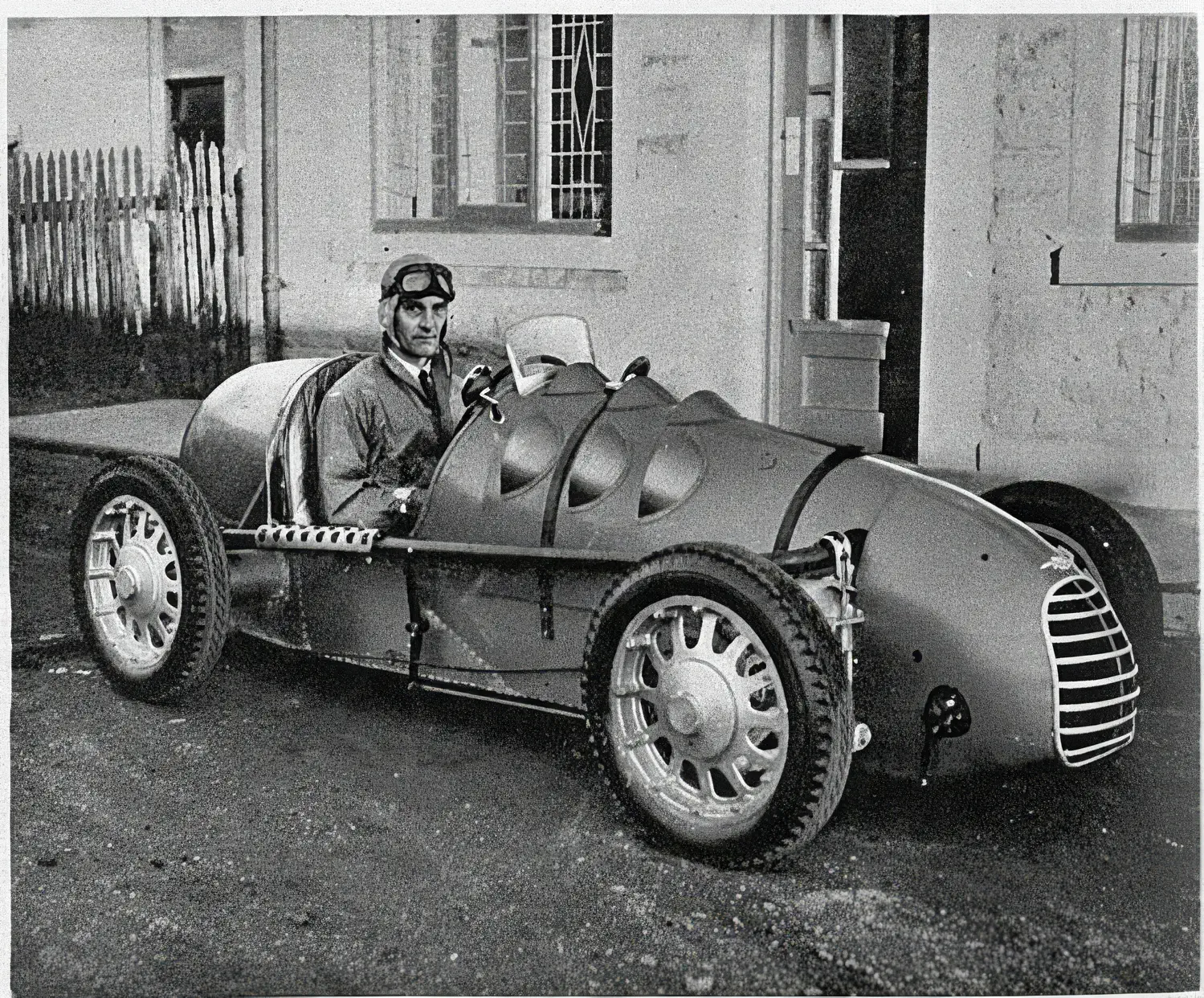

Bond's first automotive creation looked like nothing else on British circuits, probably because it was built by someone who thought British circuits were doing everything wrong. Completed in 1947, his racing car was seven feet long, twenty-three inches high, weighed less than most motorcycles, and could achieve 100mph from a 499cc motorcycle engine. The construction was pure aircraft engineering: aluminium stressed-skin with no separate chassis, no conventional suspension, and absolutely no compromises with traditional motor racing wisdom. Local observers nicknamed it the "doodle-bug," though Bond preferred to think of it as proof that everyone else was approaching vehicle construction with Victorian thinking.

The machine's debut at Shelsley Walsh proved both exhilarating and terrifying. Bond, who hadn't raced for twelve years and had tested the car for exactly 200 yards in a field behind his workshop, managed fifth place out of eight, crossing the line at over 85mph. A month later, he won his class at Bouley Bay hillclimb in Jersey. But the following year brought a sobering reminder that innovation and survival don't always coincide: Bond crashed spectacularly at Shelsley Walsh, mounting the bank and rolling his creation completely. His decision to wear a crash helmet - still considered rather precious among amateur racers who preferred cloth caps - saved his life. The locals assumed he'd been lucky. Bond knew he was simply applying aircraft safety principles to a sport that hadn't quite caught up with the twentieth century.

The People's Revolution

The racing experiments had taught Bond something that escaped most of his contemporaries: if aircraft techniques could make a competition car faster, they could make a road car affordable. In early 1948, he revealed his prototype "shopping runabout" to a fascinated press. Built in his workshop at 43 Berry Lane, Longridge, the machine weighed just 195 pounds, climbed hills that defeated conventional cars, achieved 100 miles per gallon, and cost a fraction of anything else with wheels. Or rather, three wheels, since Bond had discovered that losing one wheel saved weight, complexity, and most importantly, purchase tax - the sort of regulatory arbitrage that appeals to the British engineering mind.

The prototype demonstrated Bond's genius for practical radicalism. You climbed in over the sides rather than through doors, because doors were heavy, complicated, and expensive. The engine was a 125cc Villiers motorcycle unit, because motorcycle engines were light, reliable, and cost a tenth of car engines. The construction was stressed-skin aluminium, because that's how you built things that needed to be both strong and light. Bond needed a factory to build it properly, so he approached Lt. Colonel Charles Gray at Sharp's Commercials, asking to rent space in their Preston works. Gray refused the rental idea but made a counter-proposal that proved far more profitable for everyone involved: why not let Sharp's manufacture the car themselves? Gray had recognised commercial genius when he saw it. Production began in January 1949, and the Bond Minicar became the most successful microcar in British history. The workshop where it all started now bears a blue plaque - recognition that revolutions sometimes begin in the most unlikely places.

The Publican Engineer

Success with the Minicar should have made Bond wealthy and respectable. Instead, it revealed his fundamental incompatibility with conventional business thinking. After selling his design rights to Sharp's in the early 1950s, Bond established himself as a freelance designer, pursuing projects that fascinated him rather than projects that promised steady income. The Berkeley sports cars demonstrated how fibreglass monocoque construction could deliver racing car performance at family car prices. Formula Junior racing cars proved that front-wheel drive and lightweight construction could work in serious competition, if you were prepared to ignore traditional assumptions about how racing cars should be built.

But perhaps Bond's most characteristic career decision came in the 1960s when he acquired the Bowes Moor Hotel on the A66 in North Yorkshire. The combination of publican and automotive designer was perfectly suited to a man who had always refused to stay within conventional professional boundaries. By day, he served travellers crossing the Pennines between England and Scotland. By evening, he worked on commission design projects that kept his engineering imagination properly exercised. The arrangement allowed Bond to remain completely independent while pursuing whatever technical challenges interested him. It was typical of an engineer who had always believed that the most elegant solutions came from thinking about problems in ways that nobody else had considered.

The Quiet Revolutionary

Bond died of lung cancer in September 1974, aged sixty-seven, having lived long enough to see Chapman's Lotus dominate Formula One using principles he had pioneered in a Lancashire workshop when Chapman was still learning to drive. The irony was exquisite: Chapman received international recognition for perfecting techniques that Bond had proven viable twenty years earlier, while working with a fraction of Lotus's resources and none of their publicity machine. History would remember Chapman as the apostle of automotive lightness, but Lawrence Bond had been its quietly persistent prophet.

Whether Chapman ever consciously studied Bond's work remains unknown, but the evidence speaks with uncomfortable clarity. Both engineers shared identical obsessions with aircraft-derived construction, both understood that performance came from subtracting weight rather than adding power, and both proved that conventional automotive engineering was fundamentally wrong about almost everything that mattered. The timeline, however, is beyond dispute: Bond was first, Chapman was famous. History may celebrate Chapman as the master of lightweight philosophy, but Lawrence Bond was the engineer who proved it could work at all.