The Digital Dashboard That Ran on Hope and Smoke

In the spring of 1978, during a press demonstration, smoke began wafting from the dashboard of a brand-new Aston Martin Lagonda. Red-faced executives watched their £50,000 space-age creation begin to melt, forcing them to push the car off the display area while journalists scribbled gleefully. That single, smoking dashboard was a perfect summary of the British car industry in the 70s: a magnificent idea, followed by an embarrassing puff of smoke.

The Digital Frontier

Most car companies in 1976 were content with analogue dials that had worked perfectly well since the speedometer was invented. Aston Martin, facing bankruptcy with characteristic optimism, decided instead to invent the future. The concept was to eliminate virtually every mechanical switch in favour of over 40 touch-sensitive buttons scattered throughout the cabin. A single-spoke steering wheel maximised the view of the vast black dashboard, which resembled a spacecraft command centre when it worked and an expensive television with reception problems when it didn't. The system even included computerised voice warnings that made every journey feel like a conversation with a mildly depressed robot.

In theory, this meant the car had a brain. It could tell you your fuel economy, diagnose its own (many) faults, and control everything with the ghostly magic of electronics. It was a genuine glimpse of the future, provided, of course, the electronics felt like turning up for work that day.

Academic Ambitions Meet Automotive Reality

To create this revolution, Aston Martin called upon the graduate students at Cranfield Institute of Technology. These bright minds, armed with theoretical knowledge, created a system that weighed 180 pounds and required a 300-pair cable running to computer boxes hidden under the rear seats. When this caught fire, Aston's new director contacted Javelina Corporation in Texas, a company that specialised in electronics for F-15 fighter jets.

Brian Refoy, Javelina's president, described the original Cranfield system as "pretty much a nightmare," which from people who built fighter-jet electronics was rather damning. Within 45 days, Javelina's engineers had the Lagonda running, replacing the British university project with proper American military hardware: three actual television screens in the dashboard.

Space-Age Luxury

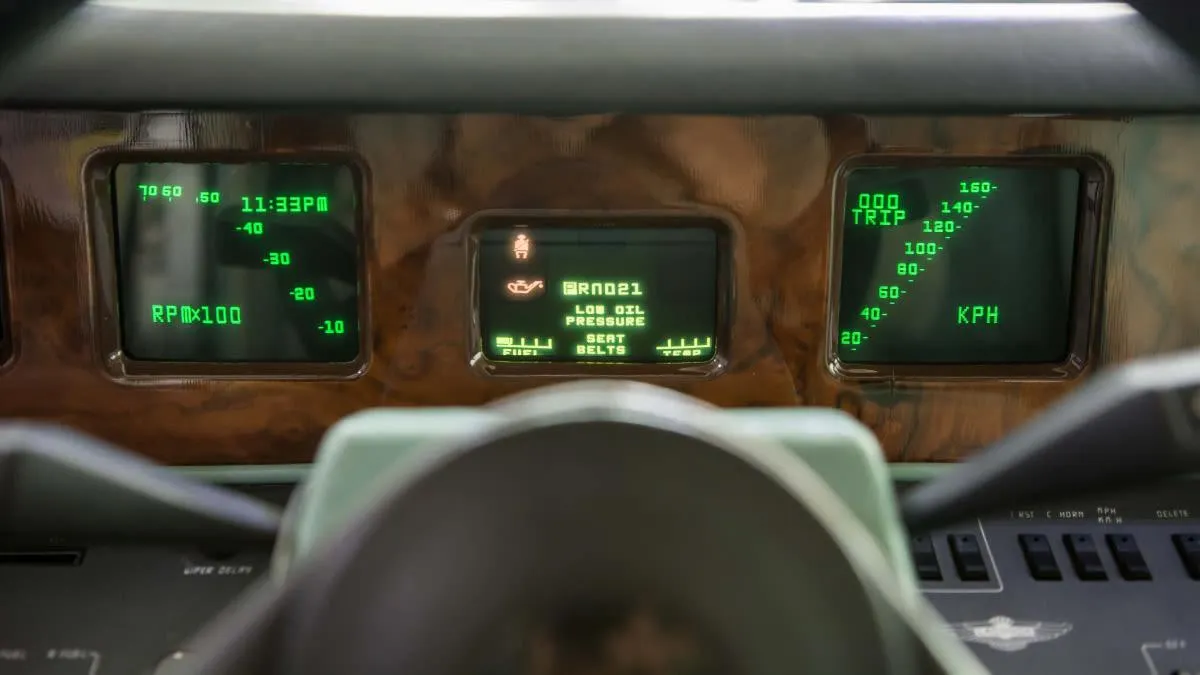

When the production Lagonda emerged in 1979, the three CRT screens displayed speed, fuel levels, and system diagnostics, all with the flickering reliability you'd expect from 1970s television technology. Touch-sensitive controls operated everything from air conditioning to door locks, while computerised voice warnings provided commentary in synthesised monotones. The dashboard's massive black panel, punctuated by glowing screens and touch controls, looked genuinely futuristic. Motor show visitors queued just to experience it.

The Price of Innovation

Development costs had spiralled. The electronics alone consumed four times the budget for the entire vehicle, forcing the final price to £50,000, roughly £300,000 today. This put the Lagonda in the same price bracket as a Rolls-Royce, which was a problem, because a Rolls-Royce came with the quaint but desirable feature of actually working. People who spent that sort of money expected a car, not a part-time job as a beta-tester for an experimental science project.

The components were supplied by Lucas Electronics, affectionately called the “Lords of Darkness” by the British press. The electronics failed with impressive creativity: touch controls that ignored human contact, displays that flickered unpredictably, and computer systems that crashed without warning. The CRT system proved even less reliable than its predecessor, generating enough heat to warm a room.

Eventually, Aston Martin abandoned the CRTs and replaced them with vacuum fluorescent displays that resembled digital alarm clocks, a strategic retreat from space-age ambition to 1980s consumer electronics.

The Magnificent Legacy

The Lagonda's commercial failure was as spectacular as its technological ambition. Time Magazine eventually included it in their "50 Worst Cars of All Time" list. Yet the Lagonda succeeded in ways its creators never anticipated. Modern luxury cars routinely feature multiple screens, touch controls, and computerised diagnostics - all concepts pioneered by this expensive British experiment.

Today, surviving Lagondas have achieved cult status among collectors who appreciate technological audacity. The car that once symbolised expensive over-ambition has become a cherished example of British engineering courage. It remains proof that someone has to be first, even if being first means occasionally providing unscheduled entertainment at press demonstrations. Lagonda was a magnificent, glorious, and almost entirely useless failure that, by some miracle, ended up showing everyone else the way forward.