Alvis: The Cars for People Who Found Bentleys a Bit Common

There have always been cars for the rich, and then cars for the fabulously, unbelievably rich. Alvis occupied a third category entirely: cars for the discerning rich. The sort of person who had already owned a Bentley, found it a little too obvious, and wanted something that was, frankly, better made. An Alvis was never a fashion statement. It was a quiet, confident, and hugely expensive nod to a fellow connoisseur, a sign that you understood the difference between a flashy brand and a technical benchmark.

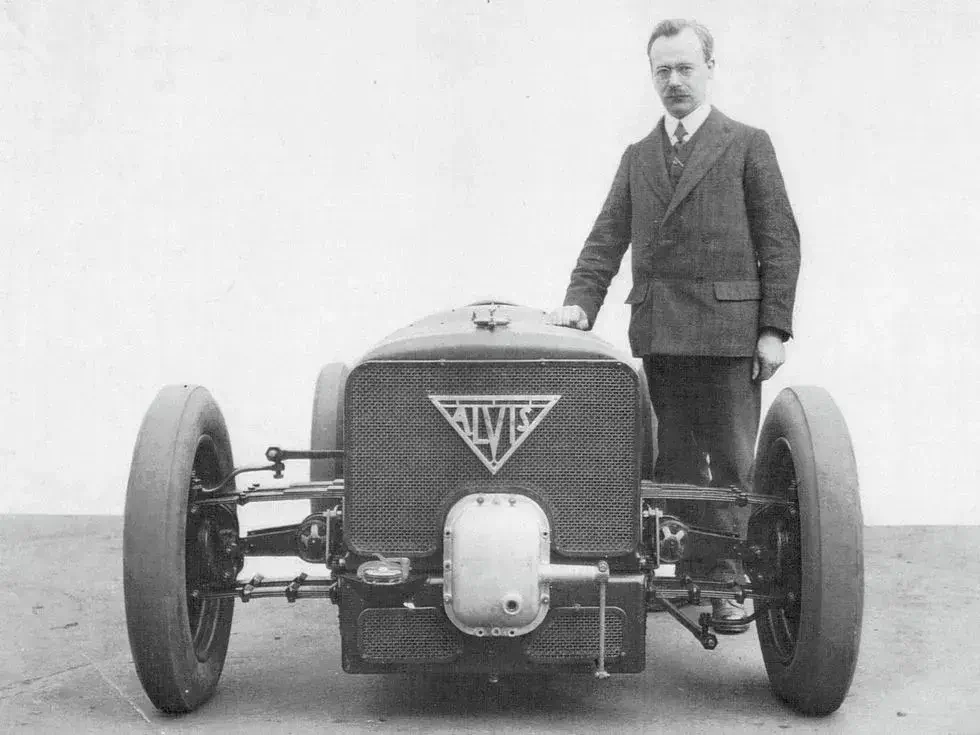

The company was born in Coventry in 1919, the brainchild of Thomas George John, a naval architect who valued exactitude above all else. Originally trading as T.G. John and Company, they adopted the name "Alvis" after deciding that a compound of 'aluminium' and the Latin 'vis' (meaning strength) sounded more impressive than "John." Other firms were content building sturdy, simple machines. Alvis preferred to show off, but in the most British way possible: by making everything work better without mentioning it. In the 1920s, when front-wheel drive was viewed as witchcraft, they were busy winning races with advanced FWD cars. By 1933, they'd developed the world's first all-synchromesh gearbox, a piece of technology so good it made every other transmission feel like stirring a bucket of bolts.

The Car Too Good to Crush

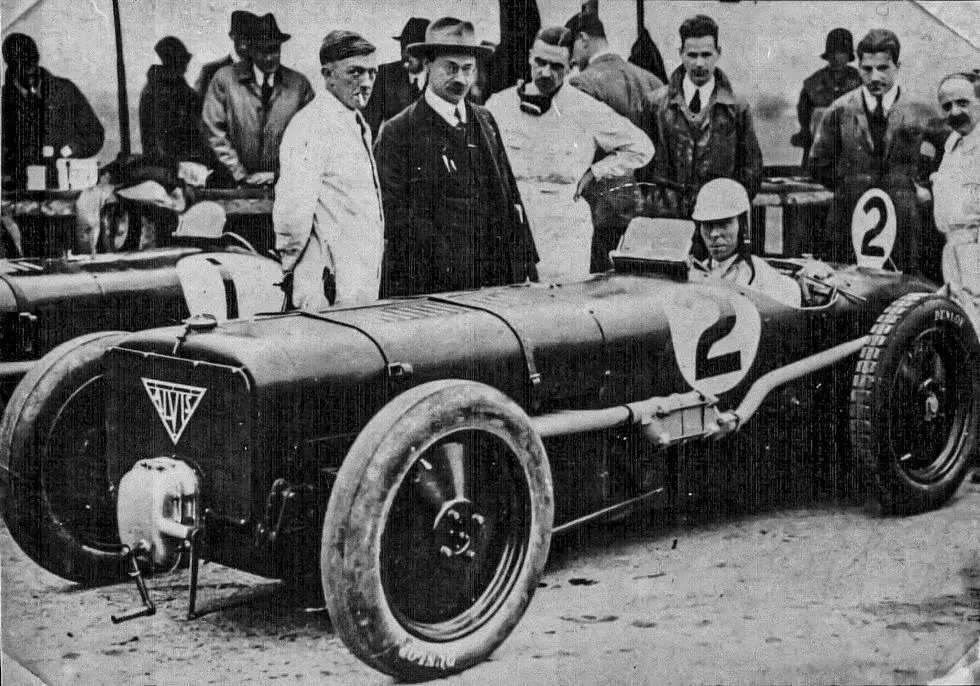

Their 1927 Grand Prix car featured front-wheel drive, independent suspension, and a straight-eight supercharged engine. It was the most sophisticated British single-seater of its day, possibly too complex for its own good. When the racing program ended, company management ordered the cars destroyed. Too advanced, too expensive, too much of a distraction.

Except the local breakers, the Roach Brothers, couldn't bring themselves to do it, so they secretly saved one of the cars and hid it away like stolen art. For nearly 50 years, this piece of surplus racing car sat in storage, too interesting to crush, too awkward to admit they'd kept. When you build something so good that even the people paid to destroy it refuse to do their job, you've achieved a peculiar kind of immortality.

Captain G.T. Smith-Clarke ran the technical side for nearly three decades, treating the factory floor like a laboratory. His chief draughtsman, W.M. Dunn would later tease Rolls-Royce colleagues about their tendency to overcomplicate everything. A Rolls, he suggested, was what happened when brilliant engineers were given unlimited time and no adult supervision. An Alvis was what happened when equally capable people had to make things actually work.

Speed Without the Shouting

By the time the 1930s arrived, Alvis had become the builder of some of the most capable and handsome sporting cars in the world. Machines like the Speed 20, Speed 25, and the magnificent 4.3 Litre were aimed squarely at Bentley and Lagonda territory. The 4.3 Litre could genuinely hit 100mph, which was fast enough that policemen would simply wave you through rather than admit their Wolseley had no hope of catching up.

Buying an Alvis in this era was a declaration, though a characteristically discreet one. You valued pioneering independent front suspension and fastidious build quality over a more famous badge. The Alvis 12/50 won its class at Le Mans in 1928, but you rarely saw owners bragging about it. That would have been vulgar.

Bombs and Paperwork

When war arrived, Alvis's exacting standards were redirected toward aero engine components and military vehicles. Then in November 1940, the Luftwaffe conducted an aggressive urban renewal program in Coventry, flattening the Alvis factory in the process. Decades of technical drawings went up in flames, which for a company obsessed with documentation was worse than losing the building.

Most firms would have folded. Alvis set up a shadow factory at Mountsorrel in Leicestershire and carried on. A workforce including significant numbers of conscripted women maintained production under conditions that would have broken less determined outfits. The company's reputation for durability was quite literally forged in fire, though they were far too polite to mention it afterwards.

After the war came the truly difficult bit: trying to sell expensive, hand-built luxury cars to a nation that was broke and living on rations. The immediate post-war model, the TA 14, was essentially a pre-war design with a fresh coat of paint. It kept the lights on, barely, while the company figured out what came next.

A Swiss Suit for an English Gentleman

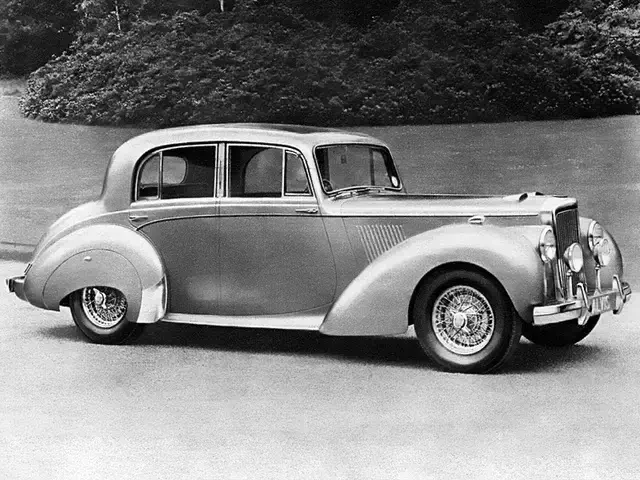

Alvis decided to focus on what it did best: a single, beautifully made "Three Litre" chassis and power unit. The early post-war cars were mechanically brilliant but looked like they'd survived the Blitz themselves. Solid, upright, hopelessly old-fashioned. The company needed modern style but wasn't about to start adding chrome and tail fins like some American fever dream.

The solution came from Switzerland, which makes sense when you think about it. If you want exactitude, subtle quality, and complete discretion, you ask the Swiss. Hermann Graber, a coachbuilder, began crafting bodies for the Alvis chassis that were perfectly muted and elegant. His designs worked so well that Alvis eventually adopted the "Graber style" for its factory cars, built by Park Ward in London.

The resulting machines, like the TD21, were stunning without being showy. The TC 21/100, known as the "Grey Lady," could hit 100mph but had the manners of a diplomat. Fast enough to embarrass sports cars, comfortable enough for the drive to Scotland, and subtle enough that you could park it anywhere without looking like you were compensating for something.

Prince Philip ordered a bespoke Graber-bodied TD21 but requested it without power steering or gadgets. Just mechanical excellence, pure and simple..

Death by Spreadsheet

Alvis prospered through the early 1960s, building a few hundred superb cars each year. By the mid-1960s, they'd produced the TF21, the fastest and most refined version yet. Sales were steady, customers were happy, the company was making a modest profit doing exactly what it had always done. Which, in retrospect, was the problem.

Small, independent craftsmen don't survive in an industry of giants. In 1965, Rover acquired the company. Soon after, both were absorbed into British Leyland, that vast corporate experiment in how to destroy multiple profitable businesses simultaneously. The new management looked at the balance sheet and were horrified. Here was a tiny operation, hand-building expensive cars that competed with products from their own portfolio. Worse, they were making them well, which made everyone else look bad.

The decision came down in 1967: Alvis car production would cease immediately. No managed decline, no final edition, no ceremony. One of Britain's most respected marques was killed off because it didn't fit on a spreadsheet. The accountants had done what the Luftwaffe couldn't.

At the time of closure, the team had been working on a prototype mid-engined V8 supercar, the P6BS. This was supposed to be the future, a thoroughly modern machine to take the brand into the 1970s. Its cancellation was the final insult. The Alvis name would continue, but only on armoured cars and tanks. The passenger car division was simply erased.

The Keepers of the Flame

The car division refused to stay dead, mainly because someone had been fastidious about paperwork. In 1968, a group of former Alvis employees founded Red Triangle in Kenilworth, named after the company's badge. They became guardians of something more valuable than most people realised.

After the war, Alvis had carried on documenting everything with near-pathological care, so Red Triangle inherited an archive of over 50,000 technical data sheets. Every car built post-war had a build sheet. If a customer in 1952 had requested a slightly different gear ratio or a specific shade of leather, someone had written it down. If they'd wanted the windscreen wipers to operate at a marginally different speed, that too was in the files. This level of record-keeping was practically unheard of, the automotive equivalent of those medieval monks copying out manuscripts so knowledge wouldn't disappear.

Want to rebuild your TA14 exactly as it left the factory? Here's the original specification. Need to know what carburettor jets were fitted to chassis number 14257? Give them a moment. That British compulsion to document everything, the same fastidious nature that made the cars work so beautifully, had accidentally created immortality.

The Return

That reputation proved more durable than the company itself. In 2009, driven by the passion of Alan Stote, who'd purchased the archives, the Alvis Car Company was officially revived. They began producing "Continuation Series" cars.

These aren't replicas or restomods. They're new Alvis vehicles, built to the original works drawings, with chassis numbers that pick up where the old ledgers left off. You can now order a brand-new 4.3 Litre or a Graber Super Coupe, complete with discreet modern upgrades like air conditioning and fuel injection, for around £325,000. Which sounds expensive until you realize you're buying a hand-built car that will still be running in 2095, maintained by people who have the original documentation for every component.

The firm from Coventry has pulled off an unusual trick: proving that if you build something correctly, document how you did it, and resist the urge to cut corners, the work outlasts the company. The cars are still here. The people who appreciate them are still here. And that quiet nod between connoisseurs, that recognition of quality over flash, substance over brand, continues. Alvis owners never needed to explain themselves. They certainly don't now.