Allard: The Sound and the Fury

The first thing you'd notice about an Allard J2 would be the sound. A noise that started deep in the bowels of Detroit, a lazy, thumping V8 burble that had no business in the genteel country lanes of post-war Britain. A bare-knuckle brawl breaking out during a vicar's tea party. American horsepower wrapped in British tin, driven by men who looked like bank managers but behaved like outlaws. The calling card of Sydney Allard, a man who looked at the delicate, balanced sports cars of his day and decided what they really needed was a personality transplant, courtesy of a sledgehammer and the biggest American engine he could find.

This was the work of a hands-on tinkerer who belonged to that peculiar British tribe of "special" builders. Sydney ran a garage in Clapham, and his career was born in the mud and grime of trials competitions, a sport that involves driving up hillsides too steep for sheep. In 1936, he built his first car, "CLK 5". He cobbled together a Ford V8 chassis with body components from a Bugatti. A Frankenstein's monster of a car that promptly won its first event at Southport Sands. The Allard philosophy was established: when in doubt, add more power. And if that doesn't work, add even more. While other British builders were pursuing balance and finesse, Sydney was pursuing violence.

A Most Fortunate War

For most of Britain, the Second World War was a catastrophe. For Sydney Allard, it was the greatest business opportunity of his life. His garage secured a massive government contract to service and maintain Ford vehicles for the British military. For five years, he became intimately familiar with every nut, bolt, and gasket of Ford's flathead V8 engine. When the war ended, Britain was broke and steel was rationed, but Sydney was sitting on a goldmine. He'd stockpiled a mountain of war-surplus Ford V8 engines and running gear, bought for next to nothing. While the rest of the industry nursed along wheezy pre-war four-cylinders, Allard had cheap, reliable American V8s ready to roar across British roads.

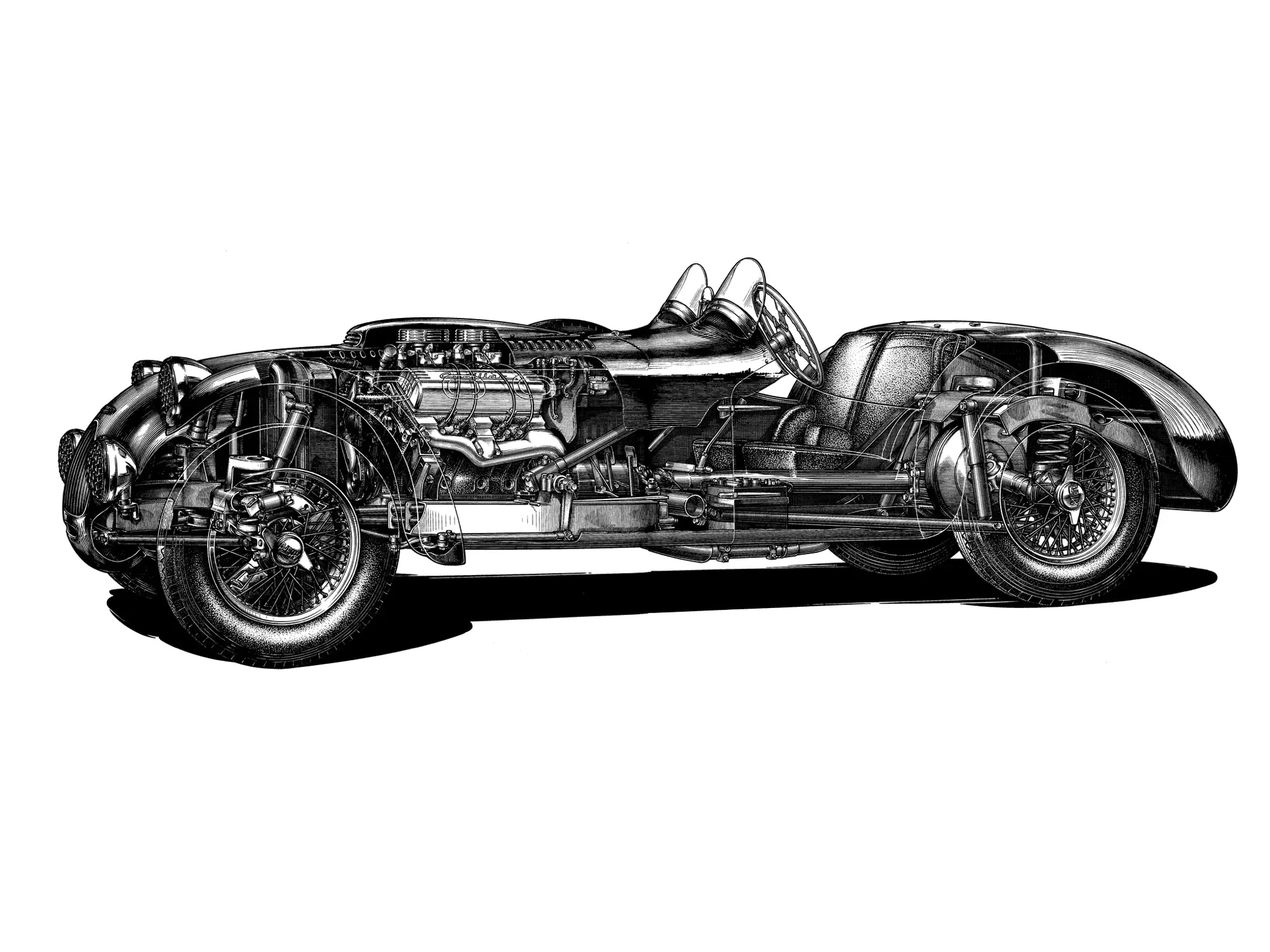

The Allard Motor Company was officially born in Clapham in 1945, and the formula was simple. Start with a stiff ladder-frame chassis, bolt on split-axle suspension that barely qualified as comfort, wrap it in thin aluminium, and then shoehorn in an enormous American V8. While companies like MG were building charming sports cars that just about managed to get to sixty, Allard was selling pure, unadulterated violence. Britain didn't quite know what to make of this colonial cacophony coming from South London. Too crude for the country club, too quick to ignore.

America's Favourite Battering Ram

The car that forged the legend was the J2 of 1949, and its successor, the J2X. Stripped of all civility, the J2 was essentially two seats, a steering wheel, and four wheels bolted pretty much directly to a V8 engine. Viciously fast, tail-happy, and requiring tremendous courage to drive properly. But Allard's true genius was in his business model. He would ship the J2 to the United States as a rolling chassis. American buyers could then install the latest, most powerful overhead-valve V8s from Cadillac and Chrysler. Americans loved the irony of it: British engineering channelled American horsepower, the whole package devoted to making expensive Italian machinery look slow.

The result was a transatlantic terror that, on its day, could humiliate the pedigreed and vastly more expensive machinery from Ferrari and Jaguar. For a few glorious years in the early 1950s, the most feared sports cars in America were being built in a garage in South London. Their competition record would make factory teams weep. The drivers who cut their teeth on them read like a roll call of legends: Phil Hill, John Fitch, and a young Carroll Shelby, who was clearly taking notes. Years later, Shelby would follow exactly the same hybrid recipe with the AC Cobra. Lightweight British chassis, powerful American engine, zero manners. He claimed he'd invented the idea. Sydney knew better. He'd written the rulebook a decade earlier.

When the Guv'nor Went Racing

Sydney Allard built these brutes all week and then raced them on Sunday. While other manufacturers sent professional drivers to protect their investment, Sydney strapped himself in and went to war.

His win in the 1952 Monte Carlo Rally is the stuff of legend. He chose his big Allard P1 Saloon, a car better suited to carrying a family to church, over any lightweight sports car designed for the purpose. In treacherous ice and snow, conditions that should have favoured nimble European machinery, he bullied the big V8-powered saloon to an outright victory. The only man in history to win the fabled rally in a car of his own name and construction. The European establishment watched a Clapham garage owner beat them in what amounted to a refined truck, and they didn't quite know whether to applaud or lodge a complaint.

His greatest triumph, however, came at the 1950 24 Hours of Le Mans. Sydney and co-driver Tom Cole entered their Cadillac-powered J2 against the might of the world's greatest factory teams. For twenty-four hours, their creation battled sophisticated machines backed by unlimited budgets and engineering departments numbering in the hundreds. Late in the race, the gearbox started to disintegrate, left them with only top gear. For Allard, this was just an inconvenience. They simply never slowed down. The massive torque of the Cadillac V8 kept the car rolling, and somehow they dragged it home to a staggering third-place finish overall. The French, who'd been racing at Le Mans since 1923, watched a British garage owner beat their best efforts with a car that had forgotten how to change gear. The sophisticates had lost to brute force, and there was something deeply satisfying about that.

The End of the Special

Of course, the glory days couldn't last. The world moved on, and sophistication eventually won. Big manufacturers like Jaguar and Mercedes started building their own highly-developed, bespoke racing cars, machines engineered by teams of specialists with unlimited resources. The Allard, for all its brute charm, began to look like what it was: a cleverly engineered special from a small workshop. After building fewer cars overall than Ferrari produced in a single good year, Allard stopped production in 1958.

But Sydney kept making noise. The firm continued and supplied Shorrock superchargers to customers who wanted more. They even created tuned Ford Anglias known as "Allardettes" for customers who wanted their sensible family cars to sound slightly unhinged. And in a final, fitting chapter, he became obsessed with a new, gloriously unsophisticated sport from America: drag racing. He built Britain's very first dragster, a supercharged Chrysler Hemi-powered rail, and became the father of British drag racing. Right to the end, Sydney Allard bolted American engines to things and made them go faster than they had any right to.

A Legacy in Smoke and Ash

Sydney Allard died suddenly of a heart attack on an April night in 1966. He was 56. In a twist of Shakespearean tragedy, that very same night, a fire broke out at the old Clapham factory. The blaze destroyed the workshop and, with it, a massive portion of the company's archives. Factory build sheets, engineering drawings, correspondence, all turned to ash and smoke. A devastatingly literal end for a man whose legacy was noise and fury.

But the story continued, because the Allard name, it turns out, is as tough as the cars. Today, Sydney's son, Alan, and grandson, Lloyd, have revived the marque. From a new workshop, they build official continuation-series cars, including the J2. They stay true to the family legacy. The sound, and the fury, are back. You can still buy a car that's fundamentally a bare-knuckle brawl wrapped in aluminium. The world chased sophistication, balance and refinement, but some people still want the sledgehammer approach. They want V8 rumble in British clothing. They want what Sydney Allard knew all along: sometimes brute force beats sophistication. Sometimes, more power is the only answer.