How a London Garage Owner Beat Ferrari with American Muscle and British Cunning

In 1950s, while big-name factory teams were spending millions on works drivers and exotic machinery, a London garage owner named Sydney Allard drove his own homemade special to third place at Le Mans. His secret weapon? A Cadillac V8 engine stuffed into a lightweight British chassis that he'd engineered in his Clapham workshop. What made this achievement even more remarkable was that Sydney had invented the formula that would later inspire both the AC Cobra and the high-performance Corvette - a full decade before Carroll Shelby claimed to have discovered the magic of Anglo-American hybrid sports cars.

The Birth of Brutal Simplicity

Sydney Allard attacked engineering problems with the methodical persistence of someone who genuinely understood that complicated solutions usually create more problems than they solve. Working from his modest garage in southwest London, he'd spent the 1930s perfecting a philosophy that the British motor industry would take decades to appreciate: why struggle with underpowered domestic engines when America was producing thunderous V8s that could be bought for sensible money?

The engineering elegance of Allard's approach lay in its refreshing honesty. Rather than trying to extract more power from wheezy British engines through elaborate modifications, he simply removed them entirely and installed American powerplants that produced twice the horsepower with half the drama. Ford flathead V8s, Cadillac units, and later the magnificent Chrysler Hemi engines found new homes in lightweight chassis that Allard designed specifically to handle their considerable torque output.

What made this formula so effective was Allard's understanding that power means nothing without proper chassis dynamics. His cars featured aluminium or lightweight steel bodywork that kept overall weight low, while the chassis design distributed the considerable forces generated by those big American engines throughout the entire structure. The result was a breed of sports car that could embarrass machinery costing significantly more money.

The Suspension Revolution

Here's where Allard's genius really shone through: his solution to the independent front suspension problem was so beautifully simple that it bordered on the absurd. Instead of designing complex wishbone systems or spending fortunes on exotic components, he took a solid Ford beam axle, cut it in half, and mounted the two pieces as swing arms. The lovely bit about this approach was how it delivered genuine independent suspension performance while using readily available, inexpensive components.

The engineering cleverness extended beyond mere cost savings. This modified suspension setup provided significantly improved handling and ride quality compared to the rigid front axles that most competitors were still using. The swing-arm arrangement allowed each front wheel to react independently to road surface irregularities while maintaining proper geometry for steering and braking. For a man working from a London garage, this represented exactly the kind of practical innovation that larger manufacturers should have been developing.

What's fascinating is how this suspension design perfectly matched Allard's overall philosophy. Like his engine choices, it achieved superior results through intelligent application of existing components rather than expensive reinvention. The system worked so well that it became a signature feature of Allard cars throughout their production run.

Racing Against the Establishment

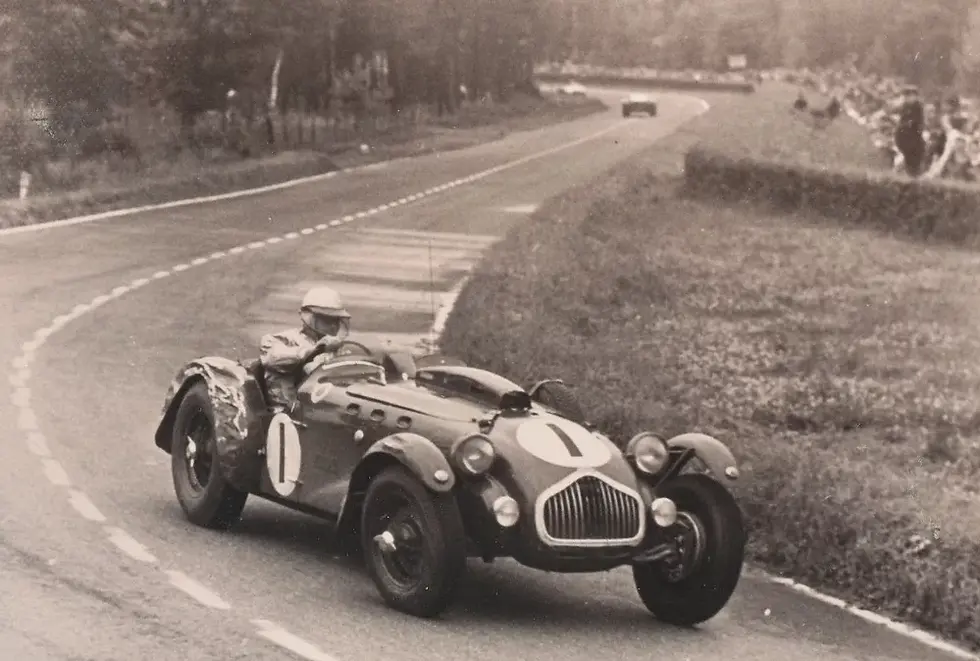

The 1950 Le Mans result proved something that British motor industry executives preferred to ignore: that intelligent engineering could triumph over corporate budgets and factory racing departments. Sydney Allard and Tom Cole brought their Cadillac-powered J2 home in third place overall, ahead of works teams from major manufacturers who had spent vastly more money on their efforts.

The achievement was particularly sweet because it demonstrated the fundamental soundness of the Anglo-American hybrid concept. While other competitors struggled with mechanical failures or simply lacked the pace to challenge the leaders, the Allard combination of American reliability and British chassis expertise proved devastatingly effective. The car completed the full 24-hour distance despite suffering gearbox problems that would have retired less robust machinery.

Even more remarkable was Allard's victory at the 1952 Monte Carlo Rally, where Sydney teamed with Guy Warburton and navigator Tom Lush to win outright in a P1 Saloon. This large, unassuming four-door car beat dedicated European rally specialists, including Stirling Moss, proving that the Allard formula worked across different forms of motorsport. British buyers have always been suspicious of anything that works too well, which perhaps explains why this success failed to convince the domestic industry to adopt similar approaches.

The American Connection

What proved the lasting value of Allard's work was how it influenced the next generation of performance car developers. Carroll Shelby and Zora Arkus-Duntov, the future father of the Corvette, both drove Allards in American sports car racing during the early 1950s. These experiences gave them firsthand appreciation of what the Anglo-American hybrid formula could achieve when properly executed.

The beauty of the Allard influence was how it demonstrated that exceptional performance didn't require exotic materials or revolutionary engineering. Shelby's later AC Cobra was essentially a refined version of what Sydney Allard had been building a decade earlier, while Arkus-Duntov's high-performance Corvette development drew heavily on lessons learned from those Clapham-built specials.

Here's what made the American racing success so significant: Allard cars consistently punched above their weight class, winning events against factory-backed teams with vastly larger budgets. The J2 series became particularly dominant in American club racing, forcing major manufacturers to reconsider their own approaches to sports car development.

The British Attitude Problem

Of course, the establishment's reaction to Allard's success was predictably dismissive. British motor industry executives seemed genuinely puzzled by the idea that American engines might offer advantages over domestic alternatives. The preference for struggling with underpowered British units rather than embracing readily available American horsepower revealed something fundamental about the national automotive psyche.

What this resistance really demonstrated was the industry's curious attachment to making things difficult for themselves. While Sydney Allard was proving that intelligent component selection could create world-beating sports cars, the major manufacturers continued pursuing expensive, complex solutions that delivered inferior results. The attitude seemed to be that if engineering was easy enough for a London garage owner to manage, it probably wasn't worth doing properly.

The problem with British car buyers was their tendency to admire struggle more than success. Allard's straightforward approach to performance - buy the best available engine and build a proper chassis around it - somehow seemed too sensible for a nation that preferred its automotive heroes to suffer beautifully rather than win convincingly.

Technical Mastery in the Details

The engineering sophistication of Allard cars extended well beyond their obvious power advantages. Sydney's chassis designs incorporated lessons learned from his pre-war special building, creating structures that could handle the considerable torque output of American V8 engines while maintaining the precise handling characteristics that British sports car buyers expected.

What made the K3 model particularly special was its use of the legendary Chrysler Hemi engine, a powerplant that would later become synonymous with American muscle car performance. The integration of this advanced engine into Allard's lightweight chassis created a combination that could compete successfully against any contemporary sports car, regardless of price or provenance.

The attention to detail extended to features like the P1's hinged windscreen, which provided controllable ventilation in an era when most cars offered precious little climate control. These thoughtful touches revealed Sydney Allard's understanding that successful sports cars needed to work as practical road vehicles as well as weekend racers.

The Legacy Question

Why do we remember Carroll Shelby as the genius behind the Anglo-American hybrid formula when Sydney Allard had perfected it years earlier? The answer probably lies in timing and marketing rather than actual innovation. Shelby arrived at the right moment with sufficient backing to turn his cars into international symbols, while Allard's small-scale operation in Clapham remained a well-kept secret among serious enthusiasts.

The lasting influence of Allard's work can be seen throughout the development of high-performance sports cars. The principle of combining the best available engine with a chassis designed specifically to exploit its characteristics became fundamental to successful sports car engineering. Modern supercars still follow this basic approach, even if they use more exotic components than Sydney Allard could have imagined.

Today's carbon fibre and titanium exotica represents a sophisticated evolution of the same thinking that led Allard to fit Cadillac engines into lightweight British chassis. The engineering philosophy - identify the best components available and integrate them intelligently - remains as valid now as it was in 1950s Clapham.

The Enduring Appeal

Allard cars continue to attract enthusiasts who appreciate their straightforward approach to performance. The Allard Owners Club, established in 1951 by Sydney himself, maintains the marque's heritage and supports restoration efforts worldwide. These cars represent something increasingly rare in modern motoring: genuine engineering integrity without unnecessary complication.

The appeal lies partly in their honesty about what sports cars should actually do. Rather than pursuing abstract engineering ideals or fashionable technical concepts, Allard focused relentlessly on creating cars that were faster, more reliable, and more enjoyable to drive than their contemporaries. This practical approach to performance car development seems almost revolutionary in today's world of electronically managed driving experiences.

Perhaps most importantly, Allard cars remind us that innovation often comes from individuals working with limited resources rather than from corporate research departments with unlimited budgets. Sydney Allard's achievements prove that intelligent thinking can overcome almost any disadvantage, provided you're willing to challenge conventional wisdom and ignore what the experts claim is impossible.