The Glorious, Unreliable Brute

The Blower Bentley is the definitive British sports car. It is the car James Bond drove in the original novels, the star of multi-million-pound continuation builds, and the enduring image of pre-war brute force, all thundering exhausts and heroic, leather-helmeted drivers. It is, in the national imagination, the car that won Le Mans. This is deeply ironic, because the Blower Bentley was a commercial disaster, a fragile and unreliable racing failure, and a car its own creator, Walter Owen Bentley, loathed with a visceral, public passion. It is a story of how the wrong car, built in defiance of its own founder, became a legend for all the right reasons.

The Argument: Displacement vs. Air

In the late 1920s, Bentley was dominating Le Mans. W.O. Bentley's philosophy was simple, robust, and effective: "There is no replacement for displacement." His 6½-litre Speed Sixes were magnificent, "the world's fastest lorries," as Ettore Bugatti sneeringly called them. They were reliable, torquey, and utterly unstoppable. W.O. knew that the Le Mans 24-hour race was won by the car that did not break. His solution to a rival's straight-line speed was, as always, to build a bigger, more reliable engine.

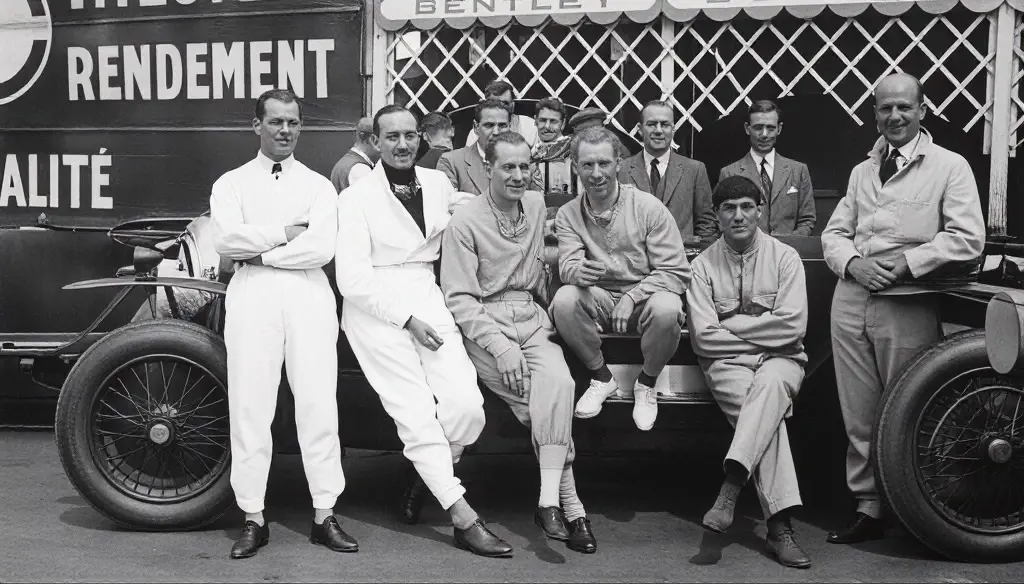

This sensible, pragmatic approach was heresy to Sir Henry "Tim" Birkin. A brilliant, dashing, and impossibly wealthy "Bentley Boy," Birkin was the embodiment of the heroic amateur. He had seen the success of supercharged European cars from Mercedes and Alfa Romeo, and he believed forced induction was the future. He proposed a new car, a lightweight 4½-litre model fitted with a supercharger. W.O. Bentley was appalled. He famously said that "to supercharge a Bentley engine was to pervert its design and corrupt its performance." This is the sound of a very great engineer watching a very rich playboy with a chequebook get his own way.

The Hired Gun

Birkin, funded by a £25,000 investment from the fabulously wealthy heiress Dorothy Paget, was undeterred. He needed an engineer to make his "perversion" a reality, and he was smart enough to know he could not go to W.O.'s team at Cricklewood. He went instead to Charles Amherst Villiers.

Villiers was the perfect man for the job. An aristocratic amateur, related to Winston Churchill, he had a reputation for tuning Bugattis and a deep fascination with supercharging. His real qualification, however, was a car he had built for Captain Jack Kruse: a 1925 Rolls-Royce Phantom with a second, 625cc engine mounted on the running board for the sole purpose of driving the supercharger. It was a magnificently absurd £16,000 experiment. This established Villiers as a brilliant, slightly mad experimentalist, precisely the kind of man Birkin needed.

Forging the Brute

In an act of open defiance, Birkin set up his own workshops in Welwyn Garden City, far from the disapproving eye of W.O. Bentley. Here, Villiers got to work. The result was the Amherst Villiers Mark IV supercharger. This was not a subtle, integrated component. It was a massive piece of industrial hardware, a Roots-type blower bolted directly to the front of the crankshaft, hanging out in the wind because W.O. had flatly refused to have it "cluttering up his engine bay." It gave the car its iconic, aggressive face.

The standard 4½-litre car produced 130 horsepower in race trim. Villiers was now force-feeding it air to produce 242 horsepower. This meant the rest of the engine was, in technical terms, a bomb waiting to explode. Villiers had to redesign its internals completely, adding a counter-balanced crankshaft, a stiffened cylinder block, and shorter, stronger connecting rods just to contain the violence he had unleashed.

W.O.'s objections were irrelevant. To race at Le Mans, the regulations demanded 50 production cars built by the manufacturer, which meant Cricklewood. Birkin was a celebrated racing driver with wealthy backers, and racing success was Bentley's entire business model. The company needed the prestige and Dorothy Paget's money. W.O. watched the factory build 50 supercharged cars bearing his name while Birkin's Welwyn team prepared the actual race machines. Engineering by committee, funded by a socialite, executed against the founder's wishes.

A Glorious, Heroic Failure

The Blower was a commercial disaster. Le Mans homologation rules required 50 production cars, which meant that despite Birkin's independent funding and Welwyn workshop, the factory at Cricklewood had to build them under the official Bentley name. W.O. watched his own company produce cars he despised, launched at the height of the Great Depression. They were ruinously expensive and almost impossible to sell. The project's cost, combined with the financial crash, crippled Bentley. In 1931, the company collapsed and was bought, in a secret bid, by its rival Rolls-Royce.

The Blower Bentley was, in every respect, a magnificent failure. On the track, it was incredibly, terrifyingly fast. It was also spectacularly fragile. It consumed spark plugs at an alarming rate, vibrated with bone-shattering intensity, and had a nasty habit of breaking.

Its entire racing legend was forged in one heroic defeat: the 1930 24 Hours of Le Mans. Birkin, in his Blower, found himself in a dogfight with Rudolf Caracciola's supercharged 7-litre Mercedes-Benz SSK. In a moment of pure, suicidal heroism, Birkin hounded the Mercedes, the two cars thundering down the Mulsanne Straight. Birkin famously passed Caracciola on the grass, with two wheels off the track, at an estimated 125 mph. He pushed his Blower to its absolute limit, eventually passing the Mercedes and breaking its will.

He also broke his own car. The Blower retired, its engine shattered. But the damage was done. The Mercedes had also been pushed too hard and expired. The real winners? The two un-blown, factory-backed Bentley Speed Sixes, W.O.'s "lorries," which had been cruising behind the drama at a sensible pace. They came in first and second. The Blower had been the perfect hare, a glorious, crowd-pleasing sacrifice so that W.O.'s tortoises could win the race.

The Bitter Aftermath

The 50 cars launched at the height of the Great Depression were ruinously expensive and almost impossible to sell. The project's cost, combined with the financial crash, crippled Bentley. In 1931, the company collapsed and was bought, in a secret bid, by its rival Rolls-Royce.

The personal fallout was just as messy. Villiers's involvement lasted less than a year. He later had to get a legal injunction to force Bentley to fit the "Amherst Villiers Mark IV" nameplate to his superchargers.

The victorious Speed Six should be the car everyone remembers. It won races, proved W.O. right, and demonstrated that proper engineering beats flashy shortcuts. History, however, cares more about theatre than correctness. Ian Fleming, a friend of Villiers, gave James Bond a 1930 4½-litre Bentley in his novels, supercharged by Amherst Villiers. The Blower had drama, a flawed heroic character, and a massive supercharger hanging off its nose. The Speed Six had reliability and victories, which is considerably less photogenic. The British have always preferred heroic failures to boring winners, and the Blower became the perfect monument to a flawed idea executed with brilliance.