Charles Stewart Rolls: The Daredevil Aristocrat

Most sons of Victorian barons were expected to master three essential skills: looking dignified at country house parties, shooting grouse without embarrassing the family name, and having firm opinions about port. The Honourable Charles Stewart Rolls, third son of the 1st Baron Llangattock, had other ideas. He preferred tinkering with engines to taking tea with duchesses, and his fellow undergraduates at Cambridge knew him not as "the Honourable" anything but as "Dirty Rolls" on account of the permanent oil stains on his clothes. His father, Lord Llangattock, hated his choice. Here was a young man born into a world of 21 servants and country estates who insisted on behaving like a mechanic.

What Lord Llangattock couldn't see was that his son's peculiar combination of aristocratic connections and engineering obsession would prove to be exactly what the infant motor industry needed.

The Boy Who Wired the Stables

Born in Berkeley Square in 1877, Rolls spent his childhood at The Hendre, the family's ancestral pile in Monmouthshire. While other aristocratic children learned Latin and deportment, nine-year-old Charles rigged an electric bell between his bedroom and the stables. A few years later, he planned and supervised the installation of electricity throughout the main house. He deployed powers of persuasion that would later make him world-famous to convince his father to pay for it. At 18, he travelled to Paris and bought a 3¾ HP Peugeot Phaeton for £225. He was one of the youngest car owners in England.

His first drive from London to Cambridge ended with a policeman stopping him for lacking the legally required man with a red flag. The journey took nearly 12 hours at a crawling four miles per hour. At Trinity College, Cambridge, he was the first undergraduate to own a motor car, spent his evenings covered in engine oil, and captained the university cycling team in 1897. He won his half-blue that year. He graduated in 1898 with a degree in mechanical engineering. By then he had already accumulated several convictions for various motoring offences.

The Dealer Who Raced Everything

By 1900, Rolls had made a name for himself on the racing circuit. He won a gold medal in the 1,000-mile trial that year, competed in the catastrophic 1903 Paris-Madrid race where 34 drivers and spectators died, and finished eighth in the 1904 Gordon Bennett Cup at the wheel of a 112-horsepower Wolseley. His racing exploits brought him fame in motoring circles, which is precisely what he needed when he opened C. S. Rolls & Co in January 1903. His reluctant father provided £6,600 to establish one of Britain's first car dealerships in Fulham.

Rolls imported French Peugeots and Panhards, Belgian Minervas, and expensive Mors machines. The business succeeded financially. His aristocratic connections and racing reputation brought wealthy clients through the door. But Rolls grew increasingly frustrated with what he had to sell. The cars were noisy, unreliable, and crudely assembled. His engineering brain craved something better, something that would not, as he put it, "rattle and smell."

Then, in May 1904, a friend named Henry Edmunds mentioned a Manchester engineer who built remarkably silent cars. The meeting was arranged at the Midland Hotel on 4 May 1904. Rolls drove a borrowed Royce 10 HP back to London, woke his business partner Claude Johnson at midnight, and announced he had found "the greatest motor engineer in the world."

The Showman Meets the Perfectionist

The partnership between Rolls and Henry Royce was a study in opposites. Royce was the self-taught working-class engineer who had sold newspapers as a boy and worked 36-hour shifts perfecting designs. Rolls was the 6-foot-5-inch aristocrat with connections to royalty and the media.

What they shared was an obsession with engineering excellence. Rolls agreed to take every car Royce could produce, and the vehicles would carry both names. Rolls-Royce Limited was formally incorporated in 1906, with Rolls appointed Technical Managing Director on £750 per annum plus four percent of profits over £10,000. Rolls proved to be a marketing genius. He demonstrated the legendary Silver Ghost's refinement by balancing a brimming glass of water on the running engine. Audiences delighted when not a drop spilled.

He won the 1906 Isle of Man Tourist Trophy in a Rolls-Royce Light Twenty, and when news reached the Derby factory, workers hoisted Royce aloft in triumph. By 1909, Rolls-Royce was established as the manufacturer of "the best car in the world," a phrase coined by Johnson, the man later known as "the hyphen in Rolls-Royce."

The Sky Calls Louder Than The Road

But cars were losing their hold on Rolls. He had co-founded a ballooning club in 1901 with Frank Hedges Butler that became the Royal Aero Club. He made over 170 balloon ascents and won the Gordon Bennett Gold Medal in 1903 for the longest single flight. In 1908, Wilbur Wright took him up for four minutes and twenty seconds near Le Mans. Rolls called it "something worth living for; it was the conquest of the air." In February 1909, he proposed that Rolls-Royce manufacture Wright aeroplanes. The board unanimously refused. In April 1909, Rolls resigned as Technical Managing Director and became a non-executive director. He quipped that he preferred flying because "there are no policemen in the air."

He bought a Wright Flyer built by Short Brothers and made over 200 flights. On 2 June 1910, he became the first person to make a non-stop double crossing of the English Channel. The journey from Dover to Sangatte and back took 95 minutes. His parents and sister watched from the Dover cliffs. He was awarded the Royal Aero Club's Gold Medal and received congratulations from King George V. One newspaper hailed him as "the greatest hero of the day." He was planning to start the Rolls Aeroplane Company.

The Price of Conquest

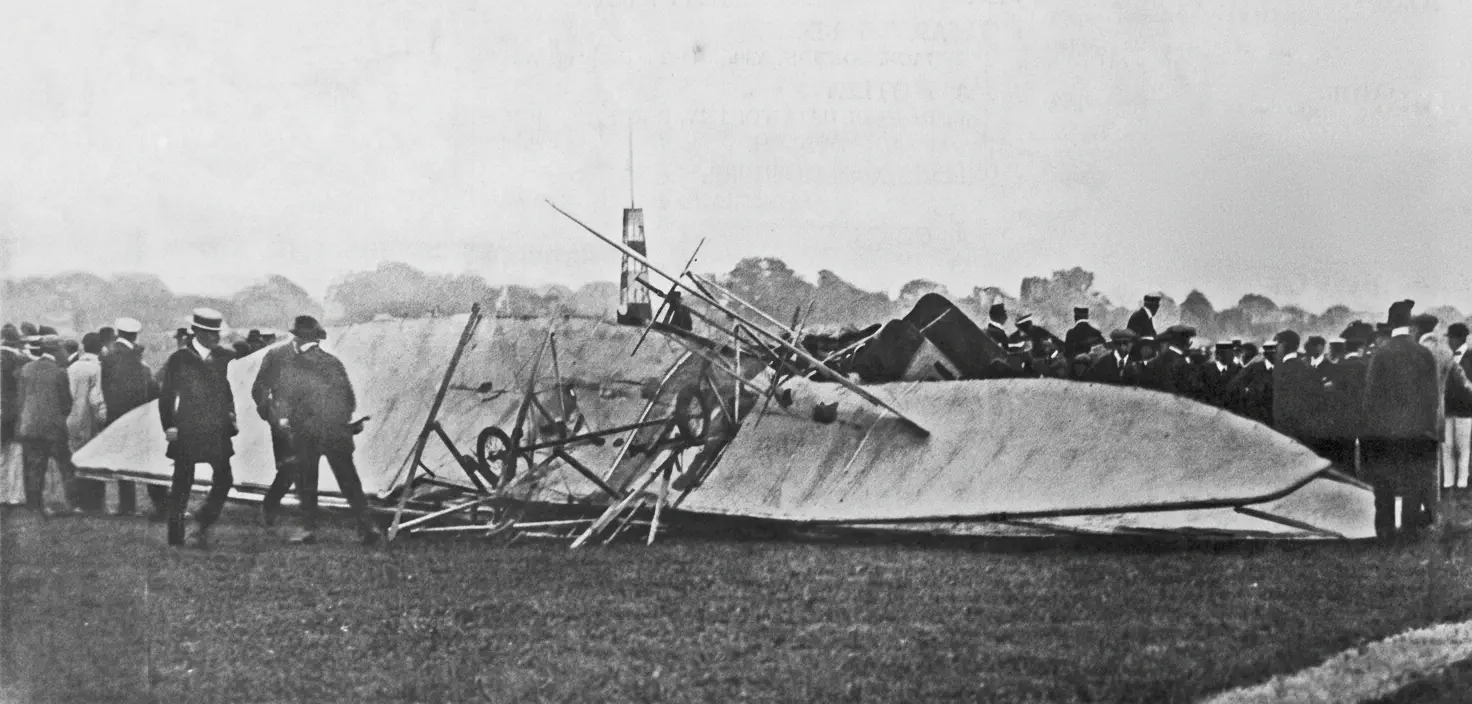

On 12 July 1910, just over a month after his Channel triumph, Rolls competed in the Bournemouth International Aviation Meeting, part of the town's centenary celebrations. The competition required landing as close as possible to a target. Winds gusted at 20 to 25 miles per hour. Another aviator, Dickson, had already wrecked his machine. Grahame-White begged the judges to cancel due to unsafe conditions. They refused. Rolls had fitted a French-built moving tailplane to his Wright Flyer just two days earlier. The modification provided better control. During his descent from about 100 feet, the modified tail broke off. The aircraft plunged to earth in a tangle of spars and canvas. It struck the ground near the crowded grandstand. Rolls sustained a fractured skull and was pronounced dead at the scene. He was 32 years old, the first Briton killed in a powered aircraft accident.

Henry Royce, the perfectionist engineer who rarely showed emotion, was in tears when he heard the news. Lord Llangattock unveiled a statue to his son in Monmouth's Agincourt Square and never recovered from the loss, dying just two years later. His other sons, John and Henry, also died young in 1916. The family's baronetcy became extinct. The partnership between Rolls and Royce lasted just six years, yet it created a brand that survived them both and still defines automotive luxury over a century later.