Cecil Kimber: The Man Who Invented the People's Sports Car

Cecil Kimber was born in 1888 to a printer's ink manufacturer in Dulwich, and nobody who knew the young man would have predicted he would build one of Britain's most successful sports car marques. He had little formal engineering training beyond evening classes and some accountancy, which he later said was more useful. His automotive passion began with motorcycles, but a severe accident on a friend's Rex shattered his right leg, which settled the matter rather definitively. He bought a 10 horsepower Singer in 1913. The man who would create the affordable sports car had found his calling through misfortune and a damaged limb, which seems appropriate for someone who would spend his life convincing people that speed and danger were worth paying for.

The Gambler Who Lost

Kimber left his father's printing business in 1914 to work for Sheffield-Simplex as assistant to the chief designer, then moved through AC Cars and finally to E.G. Wrigley, a component supplier. At Wrigley, he made the sort of decision that separates the ambitious from the sensible: he invested his own money in the company. When Wrigley lost heavily on a deal with Angus-Sanderson, for whom Kimber had styled radiators, he lost everything. It was the kind of financial disaster that teaches you either caution or determination. Kimber chose the latter.

Known as "Kim" to friends and colleagues, he was a driven man with views that would have seemed conservative even to his own conservative generation. He loathed jazz, disapproved of increasing women's rights, and would later refuse to let one of his daughters take up her scholarship to Oxford, which must have required explaining at dinner parties. He married Irene Hunt in the early 1920s and they had two daughters, Lisa and Jean. His personal life was complicated by the sort of infidelity that biographers would later document with the careful precision usually reserved for technical specifications. Here was a bundle of contradictions: a man who would revolutionise the sports car market while simultaneously believing that women belonged nowhere near universities, a gifted stylist who understood beauty alongside a businessman who had learned hard lessons about risk.

In 1921, connections from his Wrigley days helped him land a job as sales manager at Morris Garages in Oxford, the dealership owned by William Morris. By 1923, he was general manager. Morris Garages specialised in customising cars to order, which meant taking perfectly good family saloons and making them slightly less practical for slightly more money. Kimber saw an opportunity his industrialist boss had completely missed. The humble Morris chassis and engines, designed for reliability and economy, could be persuaded to do something rather more exciting. He began tuning the engines, lowering the suspension, and clothing them in sleek, lightweight bodies of his own design. He had an exceptional eye for line and colour, the sort of aesthetic sense that made engineers suspicious and customers reach for their chequebooks. He slapped a distinctive octagonal badge on the front, and MG was born.

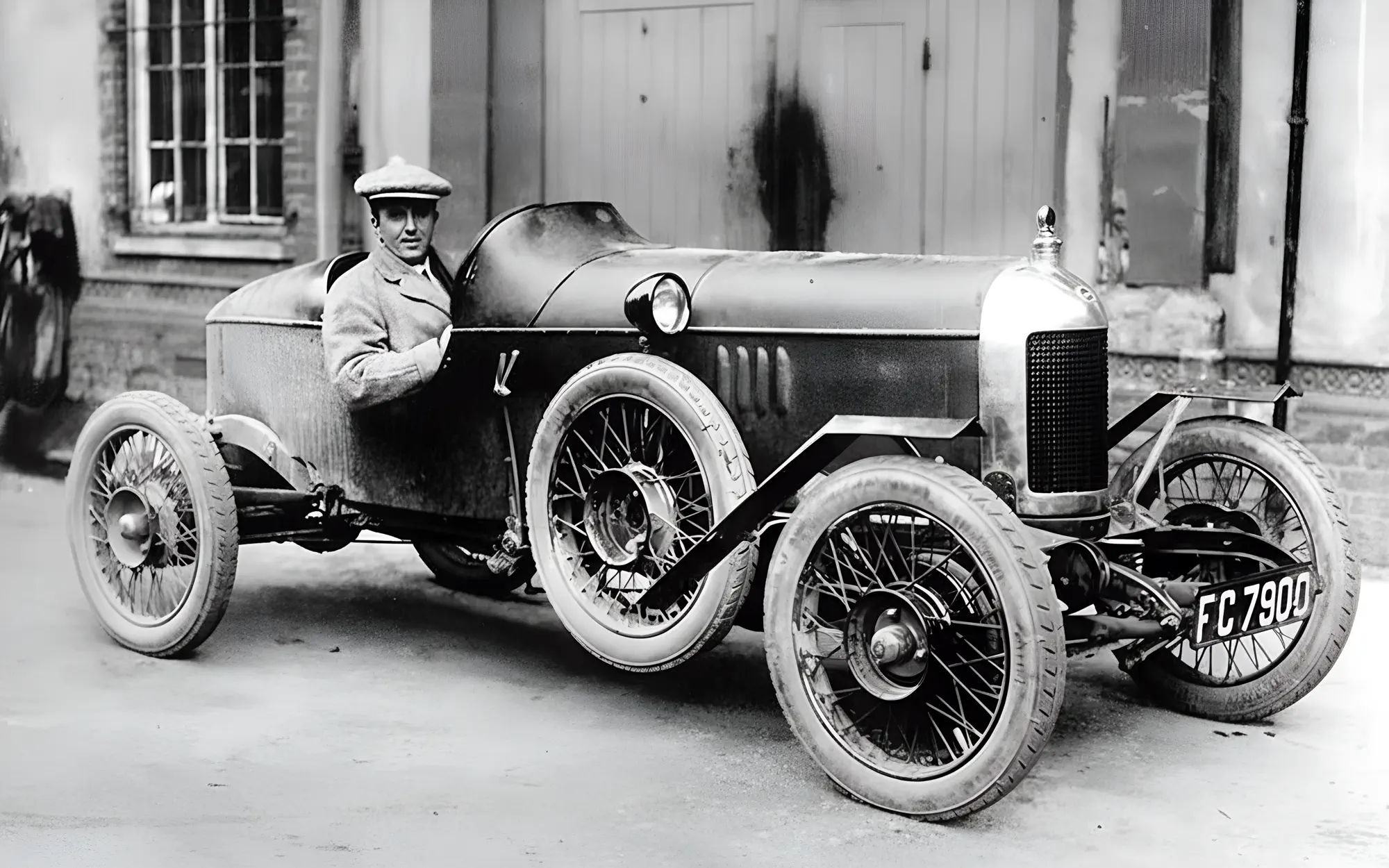

Old Number One and a Point to Prove

Kimber understood a fundamental truth about the British enthusiast: rational arguments about horsepower and valve timing were pleasant enough, but what truly mattered were trophies. In 1925, he built his own specially prepared MG and entered the Land's End Trial, a gruelling cross-country event designed to destroy cars and their drivers' optimism in roughly equal measure. The trial involved mud, rocks, and hills so steep they made participants question their life choices. Kimber won a gold medal. This was brilliant marketing disguised as motorsport. It proved that his pretty little creations could take punishment, that beneath the elegant coachwork lay something genuinely tough.

This success led directly to the M-Type Midget in 1928. Here was the revolution. It was a proper, elemental sports car, but it was priced for a junior clerk rather than a duke. It took the thrill of motorsport out of the hands of the landed gentry and gave it to anyone with a couple of hundred quid and a taste for adventure. The Midget became the world's best-selling sports car and established a formula that would define British motoring for decades: take ordinary mechanicals, make them work harder, wrap them in something attractive, and sell them to people who thought they were racing drivers.

The Soul Against the Balance Sheet

The relationship between Kimber and William Morris, now the grand Lord Nuffield, revealed a fundamental tension in British industry. Morris had made his fortune building sensible cars for sensible people, and he looked at racing budgets the way a vicar looks at a sex shop. Kimber knew that racing victories, particularly with magnificent machines like the supercharged K3 Magnette that won the 1933 Mille Miglia and Tourist Trophy, were worth more than any advertisement. He once praised an Alfa Romeo as the finest sports car he had ever driven, saying it "spurred me on in a way nothing else could have done." The difference was that Kimber would then go and build something nearly as good for a tenth of the price.

In 1935, Morris formally sold MG to Morris Motors. Kimber, who had built the company from a garage sideline into a profitable marque, was no longer in sole control. The accountants arrived, examined the racing budget with the sort of expression normally reserved for discovering damp rot, and shut the whole programme down. Kimber became increasingly disillusioned, trapped in the company he had created but could no longer direct.

The End

When war broke out in 1939, car production stopped. Irene had died the previous year, and Kimber had remarried Muriel Dewar. MG made basic items for the armed forces until Kimber negotiated a contract to build aircraft cockpits. He did this without seeking approval from Morris Motors' head office. It was typical Kimber: seeing an opportunity and seizing it. The company was not amused. In 1941, he was sacked from the firm he had built.

He found other work, first with coachbuilder Charlesworth, then with specialist piston maker Specialloid. He was preparing to bounce back, to start again. On 4 February 1945, he boarded a train at King's Cross bound for Leeds. Shortly after leaving the station, the train's wheels began slipping backwards in Gasworks Tunnel. In the darkness, the driver did not realise they were sliding downhill at six or seven miles per hour. A signalman, attempting to avert a collision, switched the points, but the train had already slid too far. The final carriage derailed, crushed against a steel signal gantry. The first-class compartment where Kimber sat was demolished. He was one of only two fatalities.

His daughter later said: "His death was nobody's fault but MG had been his be-all and end-all. It was a merciful release. He never quite got over being fired."

Cecil Kimber never saw the post-war explosion in popularity that his cars would enjoy, particularly in America. He died just as peace returned, killed in a tunnel by mechanical failure and bad luck. He was the man who made sports cars affordable, who understood that racing victories sold cars, and who knew that beauty mattered as much as engineering. He was flawed, driven, and utterly consumed by the company that bore his initials. The automotive world was built on the foundations he laid, but he was not there to see it.