The 200mph MG That Ran on Courage and Tea

In the summer of 1939, with Europe quietly packing its bags for war, a team of British mechanics were on a German autobahn trying to coax a car with an engine the size of a milk carton past 200 miles per hour. The idea was, on the face of it, absurd. The MG badge belonged to cheerful little sports cars that pottered down country lanes, not to streamlined bullets that treated physics as a polite suggestion. This was a speed for fire-breathing, aero-engined leviathans. Doing it with 1.1 litres was like trying to win a heavyweight boxing match with a well-aimed pea-shooter.

The Driver: A Calculated Risk

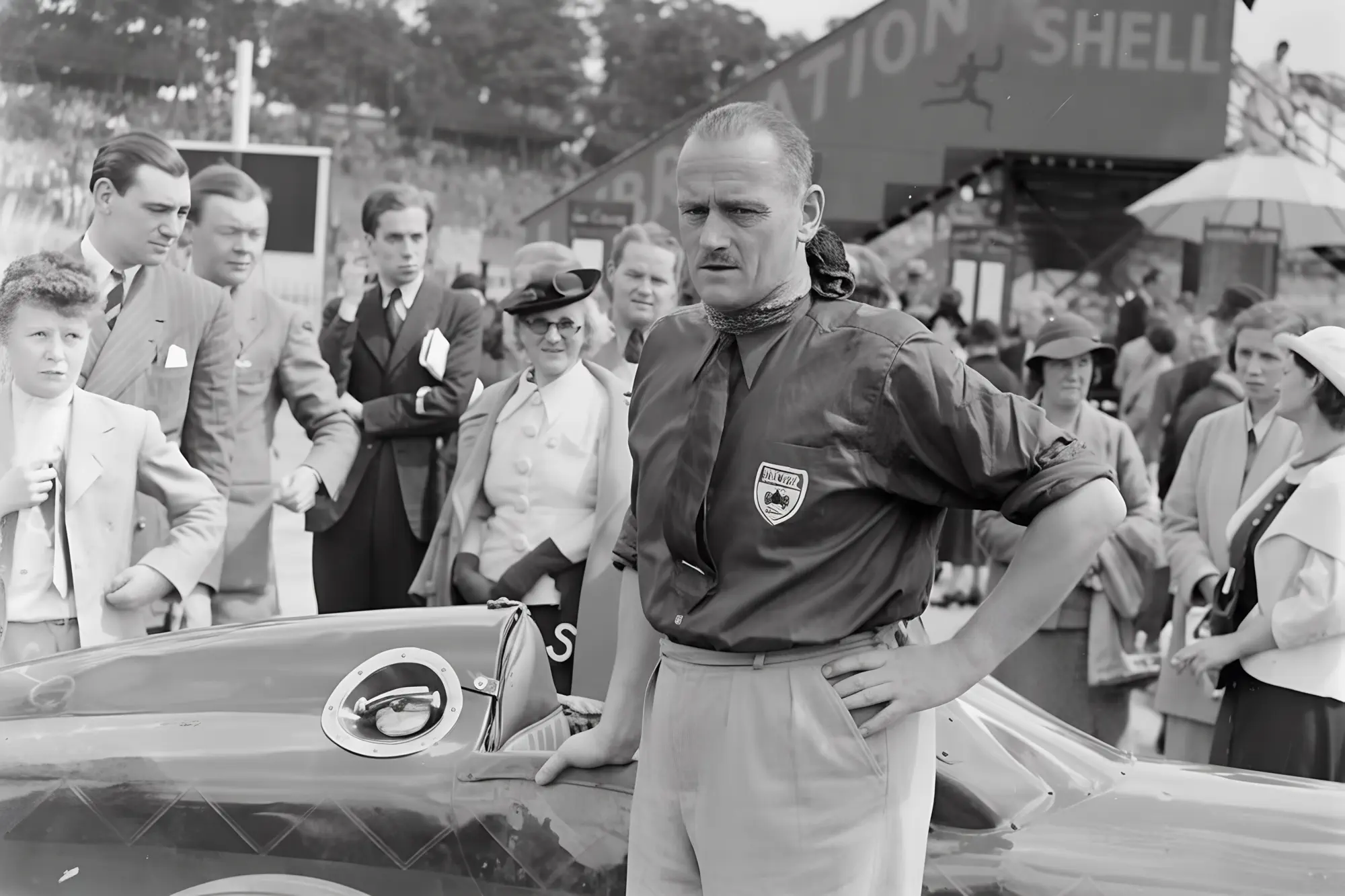

The man for this improbable task was Lieutenant Colonel Goldie Gardner, a 49-year-old veteran whose service as a pilot in the Great War had cost him a leg. On May 31st, 1939, the German soldiers watched with bemused grins as this hobbling Englishman handed his walking stick to his mechanic and prepared to fold himself into EX135. His war injuries had left him with a calm, deeply personal disregard for his own safety.

He was a meticulous planner, known for walking miles of a record course to inspect every joint and bump in the surface. This was not a daredevil; this was a calculated engineer of risk. He had come to speed records through Malcolm Campbell, serving as team manager for Campbell's Daytona Beach attempts in 1935. He was a pretty handy engineer himself, understanding not just how to drive these machines but how to get more from them. Of the claustrophobic cockpit of EX135, he famously remarked, "You don't get in it, you put it on." His motivation seems to have been a private, obsessive dialogue with the limits of the possible, a conversation conducted at terrifying speed.

The Car: A Wind-Cheating Marvel

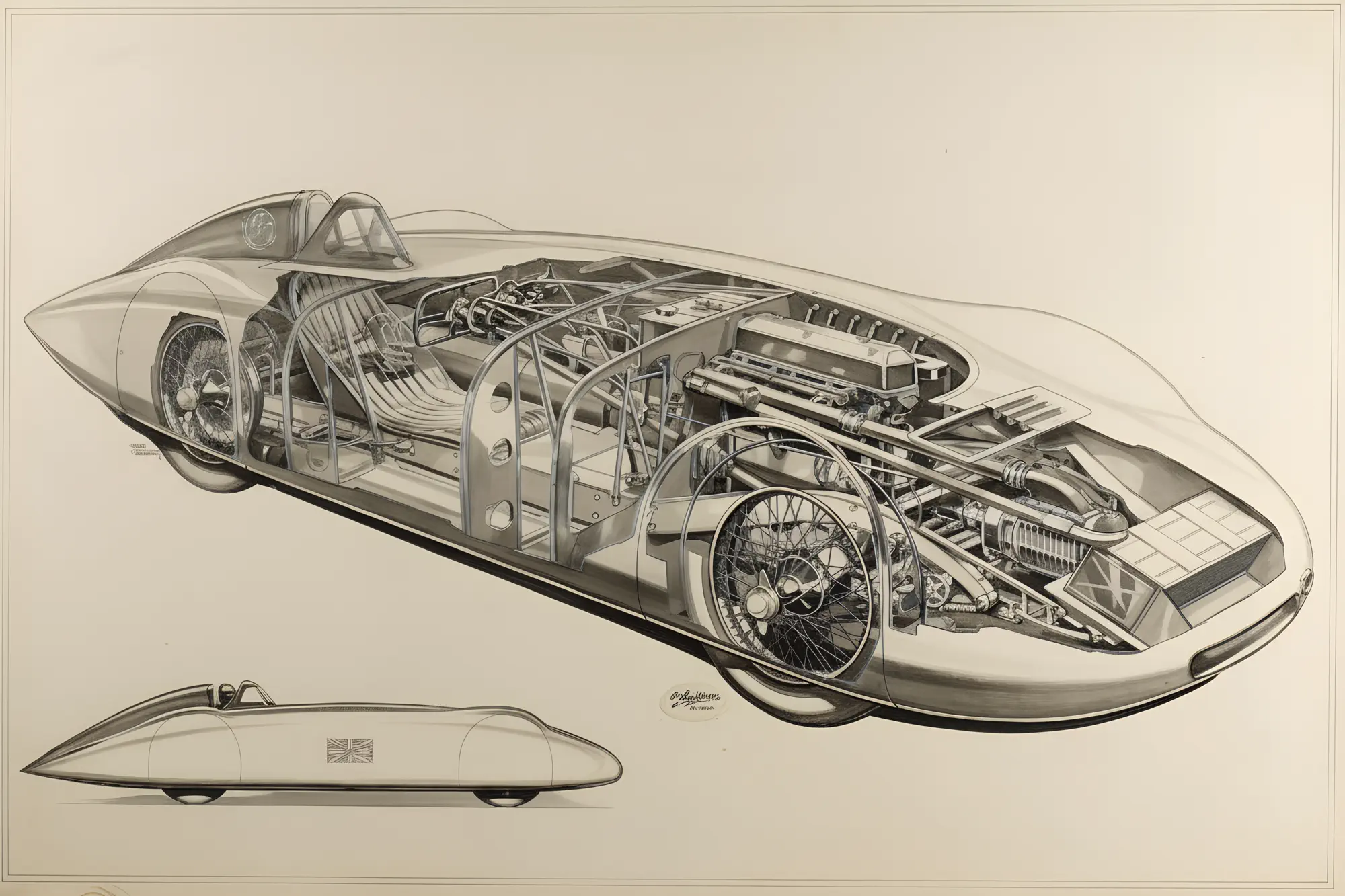

The vehicle, MG EX135, began as a K3 Magnette before Reid Railton wrapped it in a teardrop-shaped aluminium shell. Railton designed land-speed behemoths for John Cobb and thought primarily in terms of airflow. His earlier work for Gardner on a less sophisticated streamliner had caught the attention of Auto Union's Eberan von Eberhorst during Frankfurt Speed Week in 1938. Von Eberhorst took Gardner aside and suggested he would go much faster with proper aerodynamics. It was advice from the enemy that would prove invaluable.

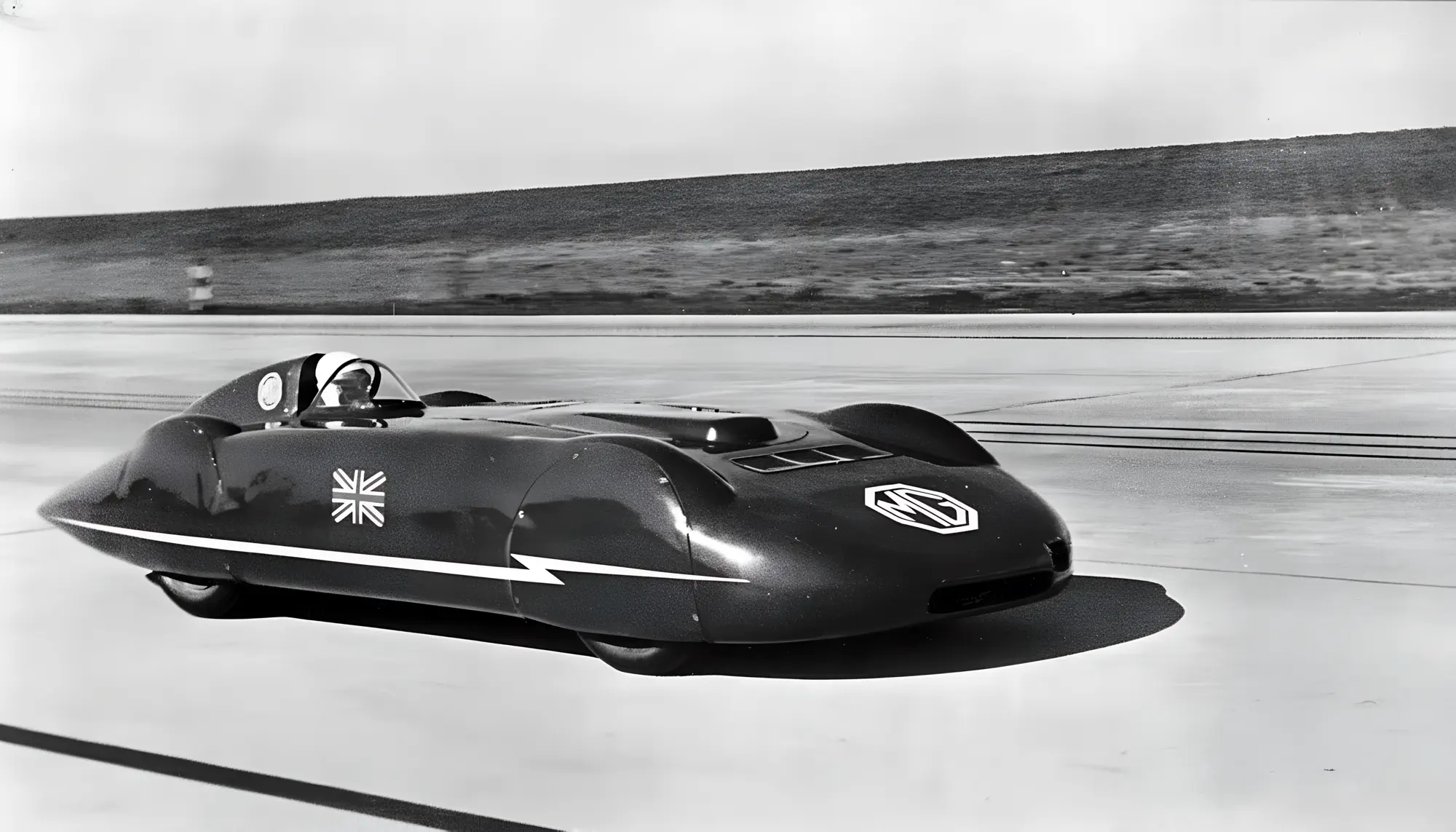

The result was impossibly low and narrow, a green lozenge designed to slip through the air with minimal fuss. The driver sat offset, his head in a tiny Perspex bubble, an organic component reluctantly added to an otherwise perfect shape.

Beneath the shell lay an engine tuned to the very edge of its mechanical integrity. The 1087cc straight-six was force-fed by a massive Zoller supercharger that screamed with piercing, high-pitched fury. The wizards at Abingdon, led by Syd Enever, had squeezed nearly 200 horsepower from the tiny block, an output that bordered on black magic. This power plant ran on a highly volatile mixture of petrol and methanol, producing a continuous, deafening shriek that was closer to an industrial accident than any normal engine note.

The German Job: A Strange Entente

The setting for this quintessentially British endeavour was, with hindsight, deeply surreal. The runs took place on the Dessau autobahn, a 10-kilometre straight stretch of new concrete designed as both record route and wartime auxiliary airfield. This was just four months before the war. A team of British mechanics, sipping tea and quietly getting on with it, were guests of the German authorities. The official timekeepers were from the National Socialist Motor Corps, men in black uniforms who oversaw proceedings with rigid efficiency.

One can only imagine the quiet, cultural bewilderment on both sides. The Germans, with their state-sponsored, cost-no-object Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz monsters, must have looked at this tiny, privately funded MG as a charmingly eccentric hobby. The British team, in turn, must have viewed the whole affair with detached amusement, a strange but necessary piece of business to be conducted before heading home. There, on a strip of concrete that would soon echo with military convoys, a moment of peaceful, absurd collaboration took place, a final sporting handshake before the lights went out across Europe.

Controlled Violence

On May 31st, 1939, Goldie Gardner 'put on' the car. The engine fired up, its scream tearing through the German countryside. Inside the cramped cockpit, the sensory overload was total. The noise from the supercharger, inches from his head, was physically painful. The vibration from the highly stressed engine buzzed through the thin aluminium chassis and into his bones. His view of the world was a vibrating, distorted slit of grey concrete seen through a tiny Perspex screen. At over 200mph, every joint in the new road slabs became a distinct, violent kick through the steering, demanding constant correction to keep the skittish, lightweight car from breaking away.

The official timing equipment registered what those present could barely believe. Over the flying kilometre, the little MG averaged 204.28 miles per hour. Gardner and his team had done it. They had pushed a car with an engine smaller than a modern family hatchback past a barrier previously reserved for giants. The car took three miles to stop, Gardner allowing it to coast to a halt rather than risk the brakes at such speeds.

The team worked through the night, reboring the engine in situ to 1105.5cc. On June 2nd, Gardner went out again and took three more records in the 1100 to 1500cc class, averaging 204.3 mph over the flying kilometre. The achievements were rather lost given the imminence of the war, but they stood nonetheless. This was the first time any vehicle under 1.1 litres had exceeded 200 mph, a victory of ingenuity over brute force, of quiet determination over state-sponsored might.

The Obsession Continues

Gardner returned after the war, seemingly unfazed by the intervening global cataclysm, and continued to set records in the same car, fitting it with progressively smaller engines. In 1952 at Bonneville, wet salt caused him to strike a marker post, which hit him on the head. The injury caused a subarachnoid haemorrhage that led to his collapse in 1953. He set nearly 150 national and international speed records in his lifetime, an obsession that consumed him from his return from the trenches until the injuries finally caught up with him. His health deteriorated until his death in 1958.

The achievement of 1939, however, remains his masterpiece. A 49-year-old veteran with a walking stick, a tiny British engine, and a team of mechanics taking tea on a German autobahn while the world prepared for war. The car, EX135, survived its ordeal and the war that followed. It sits today in the British Motor Museum, a quiet witness to a glorious, almost unbelievable footnote in the history of speed.