Morgan: The Car Factory That Time Forgot

There is a small corner of the Worcestershire countryside that is forever 1936. It's a place of old brick sheds, the smell of sawdust and varnish, and men patiently hammering pieces of aluminium over wooden frames. This is the home of the Morgan Motor Company, and it represents a peculiarly British approach to manufacturing: if something worked adequately in the past, there's absolutely no need to change it now or indeed ever. For more than a century, Morgan has been building sports cars using methods that would have seemed sensible to a Victorian coachbuilder, and people keep buying them.

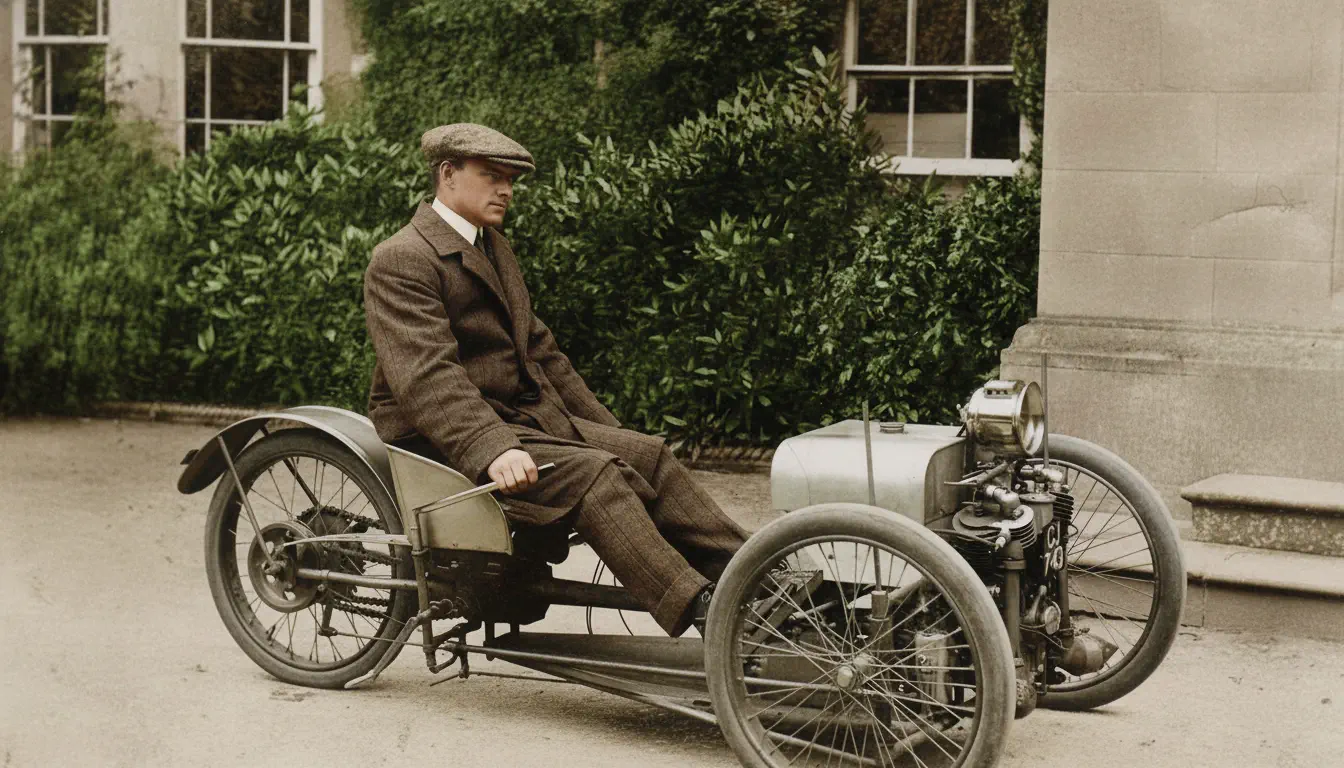

The Railway Engineer Who Preferred Three Wheels

Henry Frederick Stanley Morgan, known as H.F.S., quit his job at the Great Western Railway in 1904. He went on to run a successful motor garage business and, in 1908, began building an experimental three-wheeler in a shed. He fitted a V-twin motorcycle engine to the front, added two steered wheels and a single driven wheel at the back, and created something that was fast because it weighed almost nothing and affordable because it was taxed as a motorcycle.

An engineering master at Malvern College encouraged him to put it into production, which shows that even in 1909 some people could spot a good idea when they saw one welded together. H.F.S. displayed a two-seater version at the 1911 Olympia show. The managing director of Harrods was impressed enough to put one in the shop window, which made it the only car ever displayed there.

By 1913, the Morgan three-wheeler had won more reliability and speed awards than any other car of its kind. The Morgan family achieved this by racing their cars in cyclecar competitions throughout Europe, which was the Edwardian equivalent of modern marketing except with considerably higher chances of dying. It worked. People wanted three-wheelers built by a former railway engineer in Worcestershire, and H.F.S. was perfectly happy to keep building them.

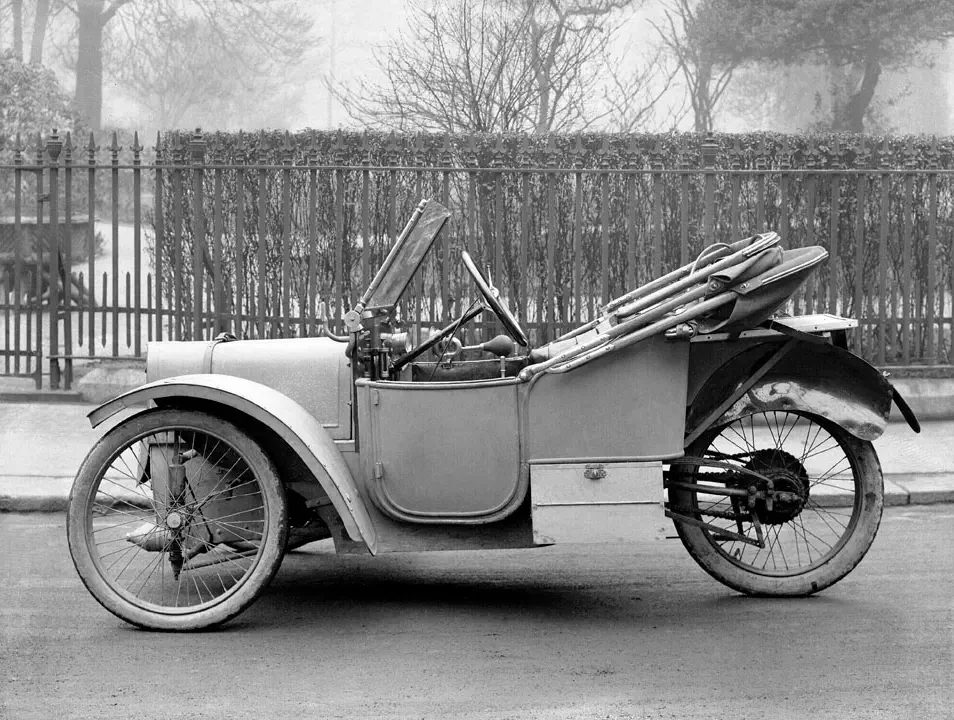

Four Wheels as a Reluctant Concession

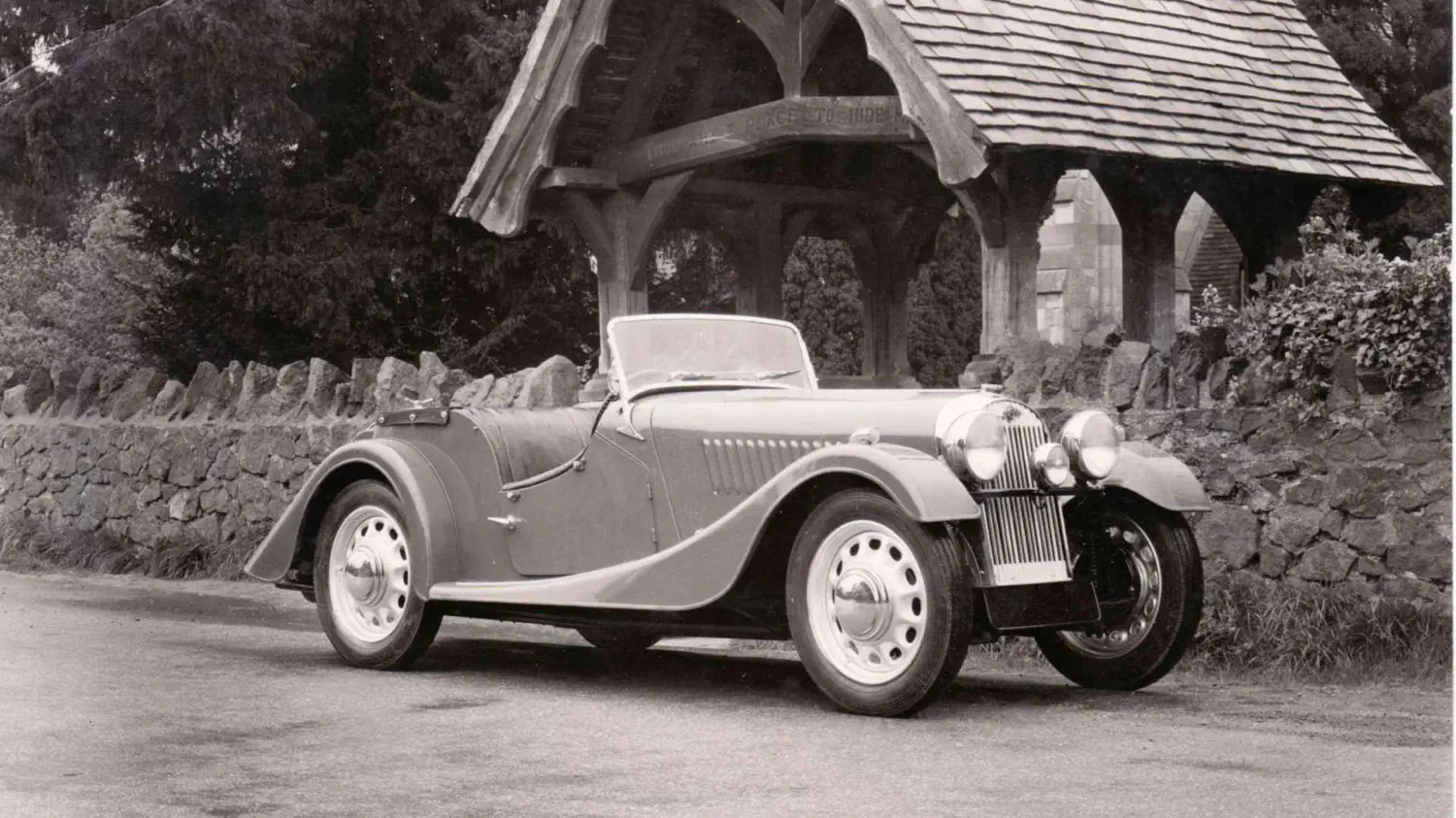

In 1936, after other customers had spent years asking for a car with four wheels like normal vehicles had, Morgan finally relented. They called it the 4/4, for four cylinders and four wheels, which was admirably literal if not exactly poetic. The car Morgan builds today, in 2025, is a direct descendant of that 1936 design. When asked why they haven't changed it, Morgan will explain at length about the virtues of their approach. What they mean is that H.F.S. Morgan built it this way, and questioning his decisions now seems presumptuous.

The construction method reveals the British relationship with tradition. The chassis is steel, sensible enough, but the frame supporting the body panels is made of ash wood. When Morgan says wood is light and strong and absorbs vibrations, they're telling the truth. When they keep using it despite having access to materials developed since 1936, they're making a statement about what matters. Progress is available. Progress is simply not interesting.

The factory still operates as it did when many of the current workers' grandfathers learned the trade. Men saw and bend timber by hand, then dip the frames in preservatives. Aluminium panels are beaten into shape over what appears to be a tree stump, though it's more sophisticated than that. Probably. The bonnet louvers are stamped out by hand using a fly-press. Each leather interior takes 30 hours to trim. The entire process takes about four weeks per car, and approximately 220 people build around 630 cars per year, which works out to roughly three cars per person annually. This is not efficient, but efficiency was never the objective.

When Someone Suggested More Power

For decades, Morgan installed small Ford engines in the 4/4 and slightly larger Triumph engines in the Plus 4. The cars were charming and handled in a unique way, partly because the front suspension design dated from 1909. Then, in 1968, someone at the factory had an idea: the car was small and light, and the Rover V8 existed, so why not combine them?

The Morgan Plus 8 was what happened as a result. Mick Jagger bought a bright yellow one in the late 1960s and drove it around London, which suggests the car's character matched his own at that particular moment in history. The Plus 8 became the car for people who wanted old-world styling with performance that would frighten modern sports car drivers. It remained in production, with updates, until 2004, which was a 36-year run for what was essentially a 1936 design with an absurdly powerful engine.

The Son Who Guarded the Legacy

Peter Morgan, H.F.S.'s son, had been running the company since 1959, overseeing both traditional models and the Plus 8's success. He ran it until shortly before his death in 2003, protecting its traditional values with the fierce determination of a man defending something valuable from people who wanted to improve it. Under his watch, Morgan continued building wooden-framed sports cars for increasingly long waiting lists. Customers waited years for cars that could have been built faster with modern methods, and nobody seemed to mind. The waiting was part of the appeal, proof that you were buying something that couldn't be rushed because rushing would ruin it.

In 1990s, Morgan sold more cars in the United States than in Britain, which was extraordinary given that American safety regulations and Morgan's construction methods were fundamentally incompatible. Getting the cars certified required ingenuity, persistence, and a certain amount of polite disagreement with regulators who thought modern cars should have things like airbags and crumple zones. Eventually, the regulations won, as they usually do, and Morgan's American sales collapsed. The company carried on building the same cars for other markets.

A Proper New Car From an Old Company

In 2000, Morgan launched the Aero 8, a genuinely new car with a bonded aluminium chassis, independent suspension, and a BMW V8 engine. The body was still formed by hand over a wooden frame, because some traditions are non-negotiable, but the chassis and suspension were modern. The styling was eccentric, with headlights that didn't quite line up in a way that made the car look surprised or possibly confused. Traditional Morgan enthusiasts weren't sure whether this represented progress or betrayal.

The Aero 8 was Morgan's declaration that it hadn't been asleep, just extremely selective about which developments from the past 70 years seemed worth adopting. Independent suspension: yes. Computer-aided design: perhaps. Abandoning wooden body frames: absolutely not. It was entirely Morgan's approach to modernity - accepting just enough of it to remain viable while rejecting anything that interfered with doing things properly, which meant doing them as H.F.S. had done them.

When the Italians Bought the Wooden Car Factory

In 2019, after 110 years of family ownership, Morgan was sold to InvestIndustrial, an Italian investment group. The traditionalists worried, fearing the Italians would modernise the factory, install robots, and start building efficient cars that resembled everything else. The fact that this would make commercial sense made it more frightening, not less.

The new owners appear to understand that Morgan's value lies precisely in not making commercial sense by normal standards. They've invested in the factory, launched new models using aluminium platforms, and brought back a modern version of the three-wheeler. But they've kept the wooden-framed cars in production. The factory still looks like a place where skilled craftsmen make things by hand because that's how those things should be made. Cars in various stages of completion, each with a build ticket bearing the customer's name, move from shed to shed. Workers trim door panels with tin snips until they fit, which is slower than using modern tools but produces the same result with considerably more satisfaction.

While other manufacturers automated and expanded and chased efficiency, Morgan kept building cars the way H.F.S. built them, and it turns out there are enough people who find this approach appealing to keep a company of 220 people employed building 630 cars per year. That's not mass production. It's barely production at all. But there's still a corner of Worcestershire where 1936 continues indefinitely, where wood and aluminium and leather are assembled by hand into cars that look like they should have been built decades ago, because that's how they've always been built and nobody's found a compelling reason to stop.