Frederick Lanchester: The Man Who Invented the Car and Died Unable to Afford One

The British motor industry has never quite known what to do with its genuine geniuses. It handles them like fragile ornaments - admired, occasionally dusted off, then quietly forgotten. Frederick William Lanchester was one such ornament: a man who effectively drew the blueprint for the modern motorcar, only to spend his later years unable to afford one. Britain celebrated his brilliance just enough to feel good about itself, then left him to count the pennies.

A Mind Without a Blueprint

Born in 1868, the son of an architect, Lanchester treated formal education as an optional exercise. He left science college without a qualification but with a brain fizzing with ideas. A small legacy gave him enough income to ignore the tedium of respectability and start thinking. After seeing the early motorcars of Paris, he returned home convinced he could do better. Where others saw a cart with an engine, he saw an opportunity to start from scratch.

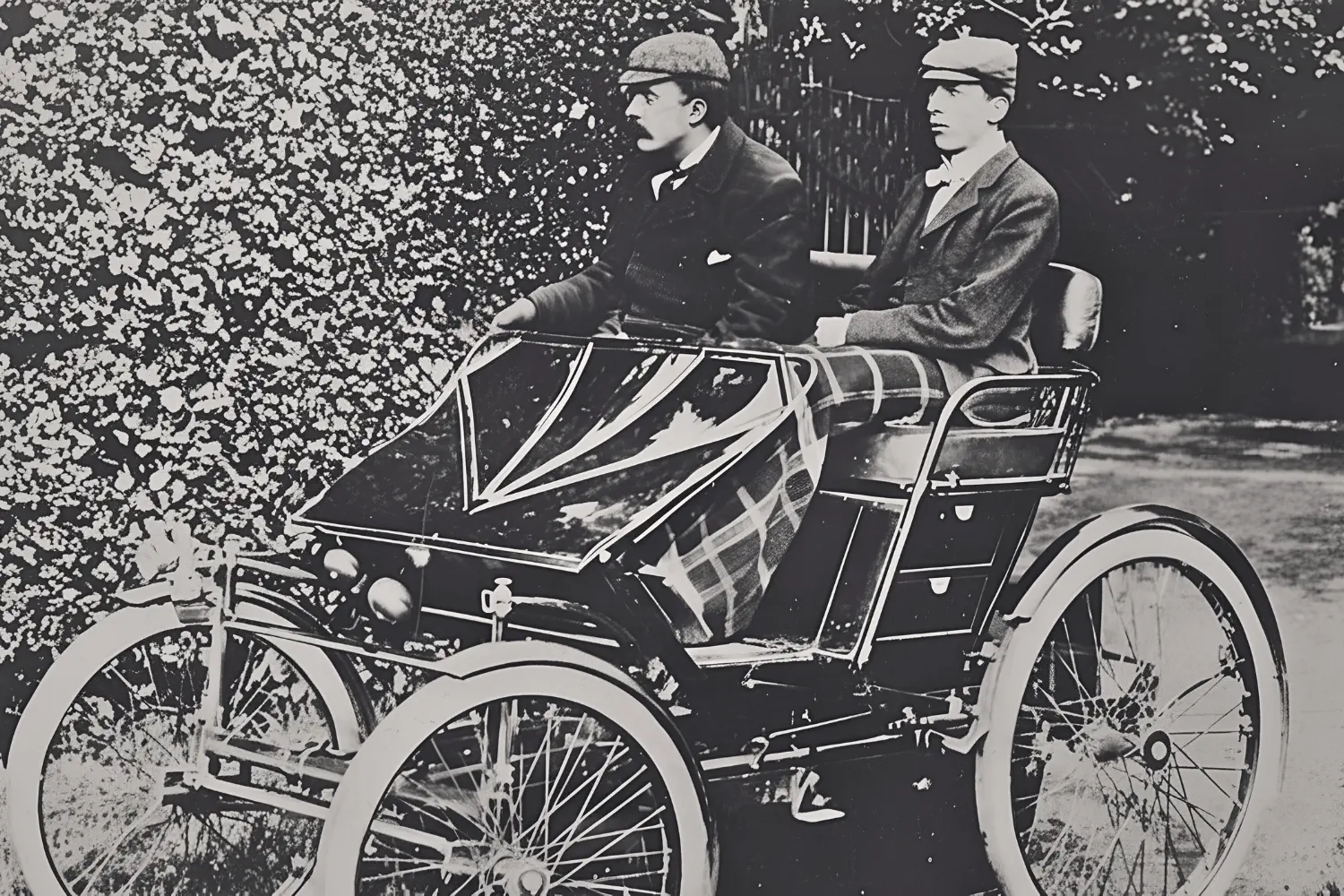

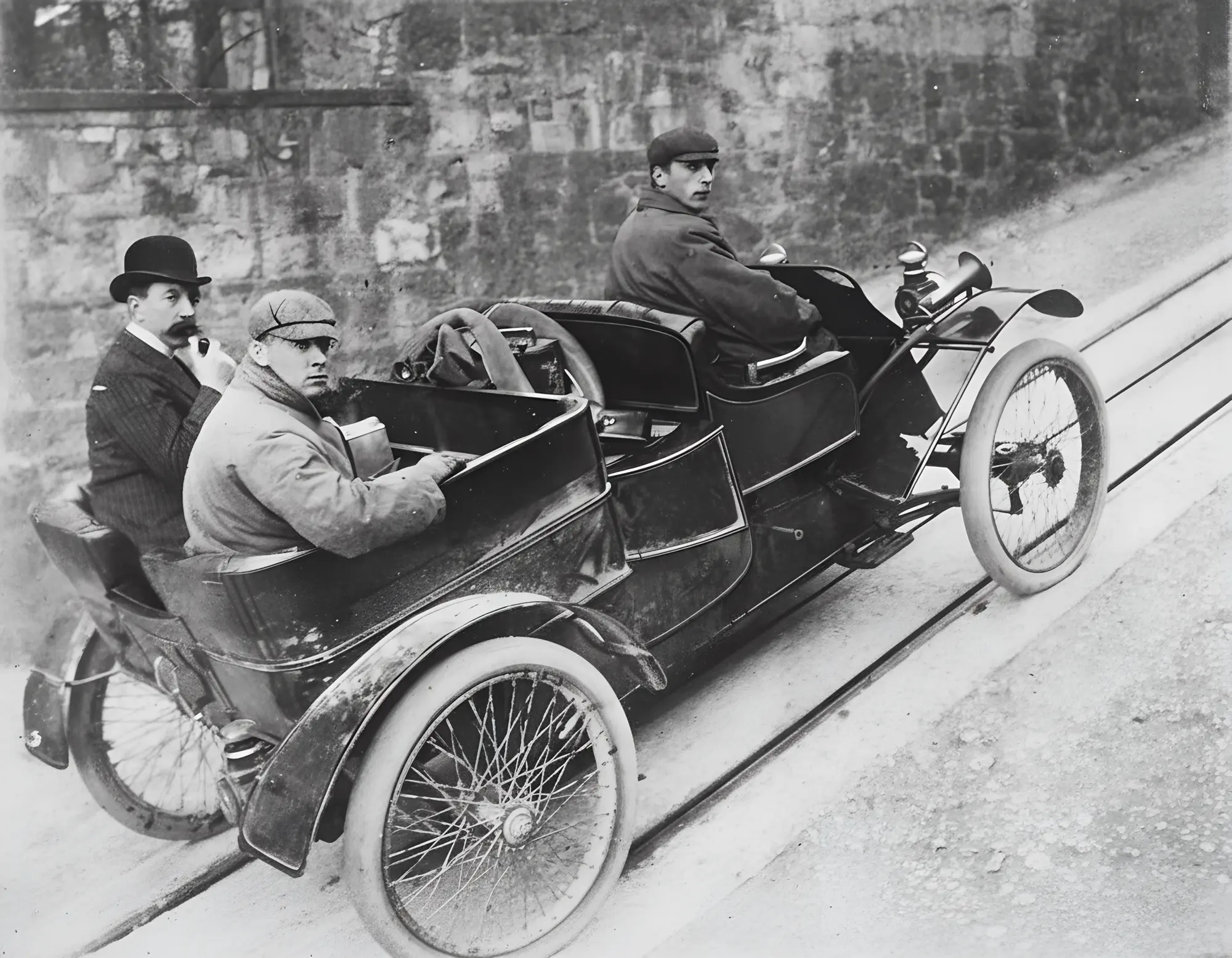

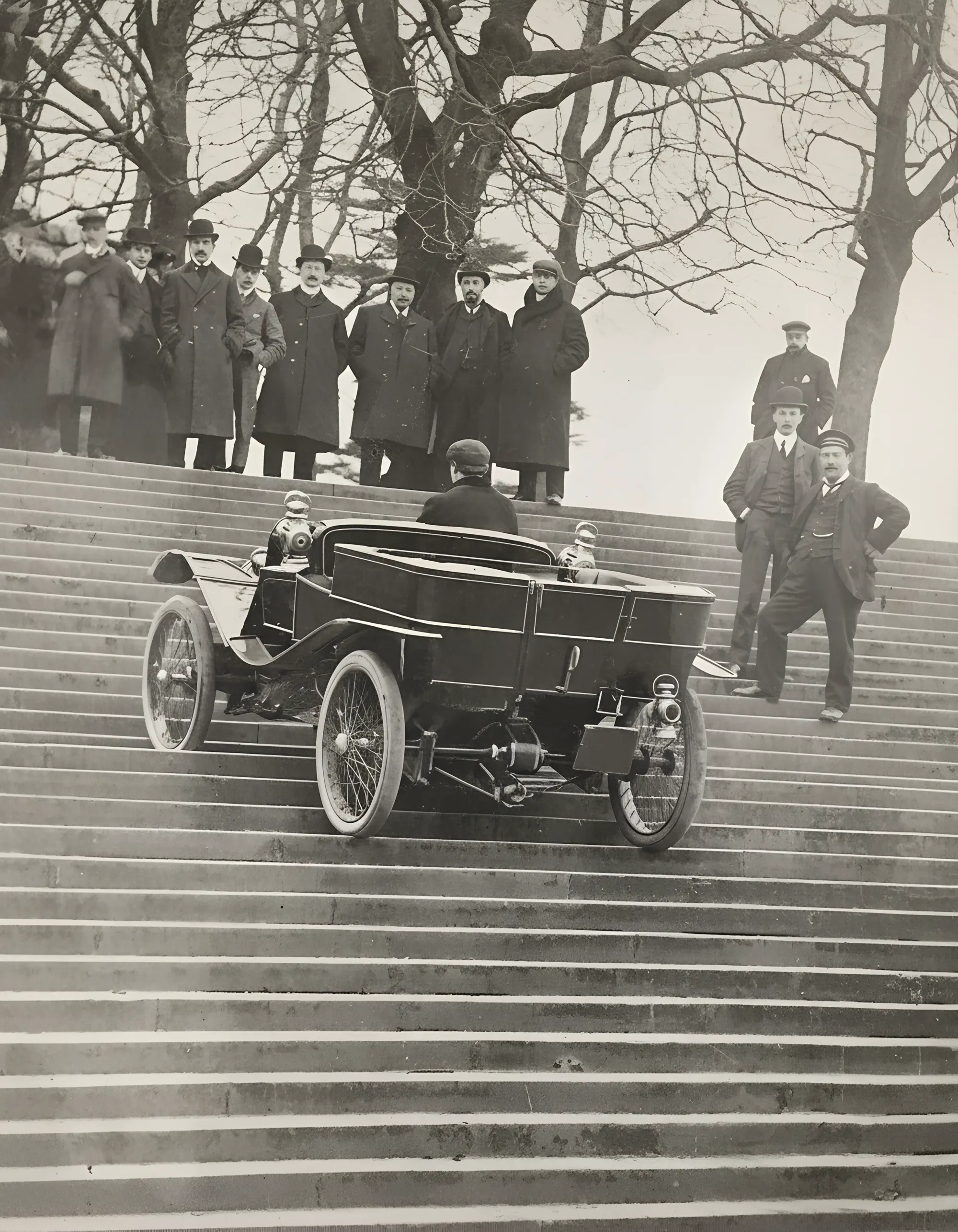

In a small Birmingham workshop, he and his brothers began to build a car that owed nothing to anything before it. By 1895, he was driving it on public roads, unconcerned by the Red Flag Act or anyone else’s opinion. The result was astonishing. His twin-crankshaft engine cancelled vibration long before anyone thought to try. He used epicyclic gears years before Ford made them famous, built his own gear-cutting machinery, and created a worm-drive axle smoother than anything else on the road. His suspension was supple, his controls were grouped logically, and his seats could be adjusted. He even fitted a transmission brake that would evolve into the disc brake. Every part of the machine bore the stamp of original thought. He wasn’t copying progress; he was inventing it.

A Mind Few Could Follow

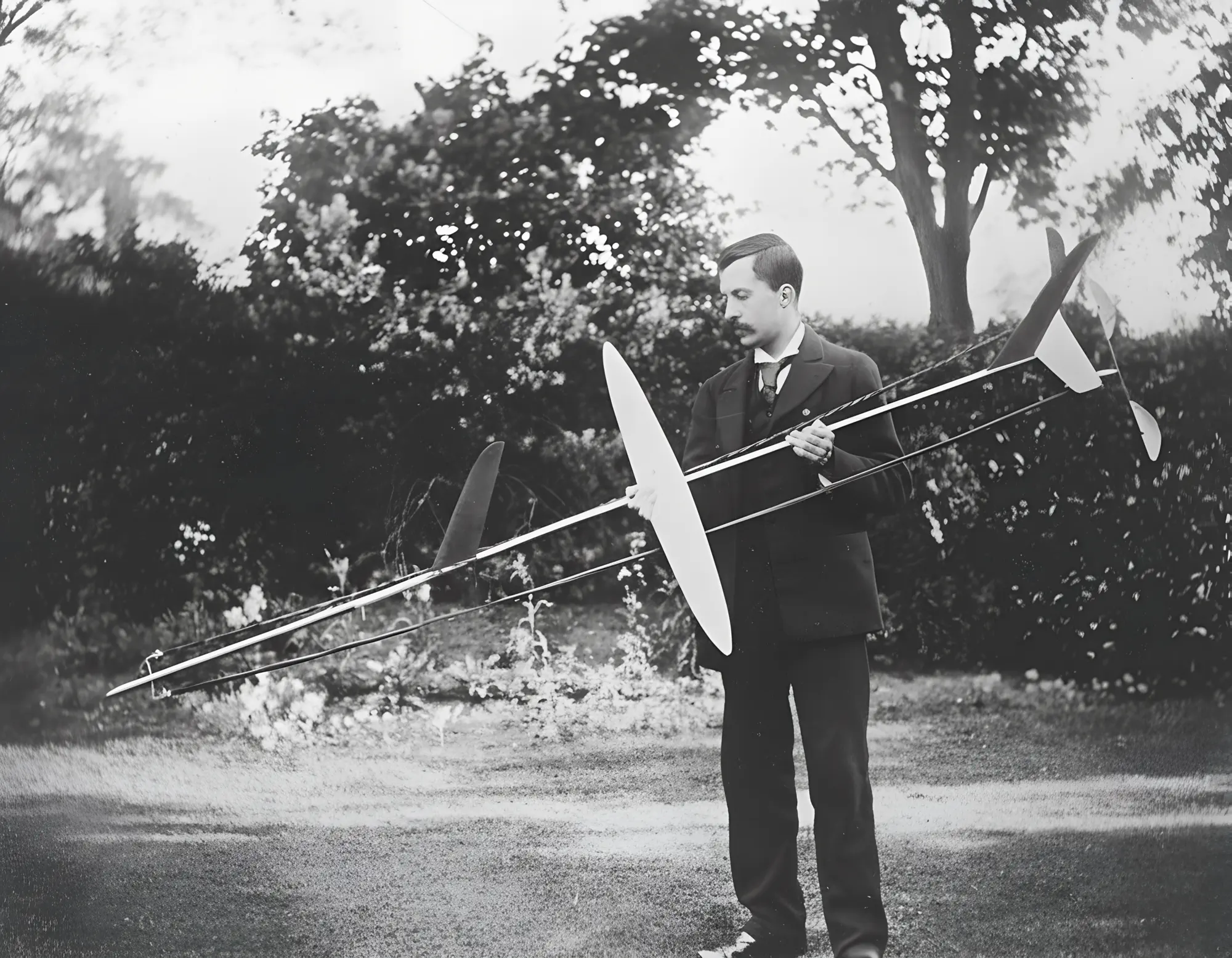

Genius is rarely user-friendly. While Lanchester was designing cars, he was also busy discovering the principles of flight. In 1897 he presented a paper on how wings create lift, which the Physical Society rejected because they didn’t understand a word of it. One historian later explained that Lanchester’s language was “almost incomprehensible.” That, in a way, was the problem. He saw too far ahead and spoke in equations while everyone else was still arguing about rivets.

Contemporaries described him as large, slightly awkward, and prone to paradoxical remarks. He could charm a room and lose it in the same sentence. His books on aerodynamics were brilliant but heavy going, like reading the Bible through a telescope. The men building aeroplanes simply nodded, smiled, and carried on stitching the canvas.

An Education in Business

Lanchester’s trouble was not invention but income. His cars were excellent, his balance sheet less so. Frank Lanchester, the more polished brother, did his best to promote the company, but it was never solvent. By 1904 it was in receivership. A businessman rescued it on terms only a desperate man would accept. Lanchester was reduced from managing director to consultant and stripped of his shares. He concluded, with reason, that financiers were an inferior species.

The pattern was familiar even then: Britain’s engineers could build anything except a successful business model. It is hard to imagine an American or German industry allowing such a mind to slip through its fingers, but Britain has always preferred a steady hand to a dangerous brain.

A Brief Spell of Harmony

In 1909, Daimler hired Lanchester. To his surprise, he found a civilised environment where he was allowed to think. It was there he devised the torsional vibration damper, the clever little device that stopped six-cylinder engines shaking themselves to pieces. It was patented in 1910 and earned him royalties for years. For a brief period, he was celebrated. He attended conferences, gave papers, and was treated as the national treasure he should have been all along.

The Quiet Tragedy

After the Great War, Daimler turned its attention to mass production, which bored him rigid. He left in 1929 and drifted back into obscurity. Illness followed, including Parkinson’s disease and failing eyesight. His wife Dorothea became his amanuensis, taking down notes when his hands no longer could. The man who had invented half the car’s moving parts could no longer afford to own one. Books, once his passion, were now beyond his means.

His final years were painfully British in their restraint. The industry took up a collection, raising a pitiful sum to keep him afloat. He accepted it with quiet dignity and a weary sense of irony. “It is an amazing experience,” he wrote, “to find that, without any loss of my faculties, the world has no use for me.” Frederick Lanchester died in 1946, supported by an industry built almost entirely on his ideas. Britain has never been short of geniuses; it just keeps forgetting where it put them.