F. R. Simms: The Forgotten Godfather of British Cars

Frederick Richard Simms is the ghost at the feast of British motoring. He is the man who laid the foundations. He brought the commercial rights for the high-speed petrol engine to Britain. He founded the RAC. He organised the first SMMT-backed motor show. He built the first purpose-built armoured car prototype. He even championed the word "petrol" because the industry needed a snappy name. He was the great organiser of the industry, only to be politely airbrushed out of the family photos.

Simms was born in Hamburg in 1863 to a British father and a German mother. This dual heritage was his greatest asset. It gave him a foot in both camps. He possessed the engineering brilliance of Germany and the commercial ambition of Victorian Britain. He was educated as a mechanical engineer in Berlin and London, which meant he could not only design a machine but explain in two languages why it was currently on fire.

The Bremen Meeting

Destiny arrived in 1889. While supervising a cableway installation at an exhibition in Bremen, the 26-year-old Simms met Gottlieb Daimler. Daimler was then in his mid-fifties. He had already developed the high-speed petrol engine that would change the world. The two men struck up a close friendship. It was a meeting of minds that would eventually ruin the peace and quiet of every village in England.

Simms recognised that this noisy and smelly German invention was the future. In a move of incredible foresight, he secured the rights to use and manufacture Daimler’s engines in Britain and the Empire. He became Daimler’s commercial gatekeeper in London. Anyone wanting access to the most advanced engine technology in the world had to go through Fred.

Terrorising the Swans

Simms did not initially want to build cars. He thought the British public was too conservative and too fond of horses to accept them. Instead, he thought the engine belonged on the water. In 1891, he set up a firm called Simms & Co and began fitting Daimler engines into motor launches.

He spent the early 1890s buzzing up and down the Thames in petrol-powered boats. He terrorised the swans and tried to convince sceptical investors that explosions were a viable form of propulsion. In 1893, he formed the Daimler Motor Syndicate. While often cited as one of the first motor companies in Britain, it was a humble start. The office was probably a desk and a filing cabinet, but it held the patents that would build an empire.

The Smuggler and the Pony Counter

Boats were merely the prelude. His real contribution was recognising that the car was inevitable. In 1895, he did something spectacular. Along with his friend Evelyn Ellis, he imported a Daimler-powered Panhard from France and brought it to England.

The July 1895 journey from Micheldever to Datchet amounted to a declaration of intent. It was one of the first long-distance petrol car journeys in Britain. Simms rode shotgun. He carefully noted the reaction of the horses they passed. He later famously remarked that out of hundreds of animals, only "two little ponies" seemed genuinely upset. It was a classic Simms move. He used data to debunk the hysteria of the anti-motoring lobby.

Simms soon realised that to build a car industry, he needed capital. In 1895, he sold his Daimler Motor Syndicate and its precious patents to a financier named Harry J. Lawson. Lawson collected companies with the manic energy of a stamp collector. He wanted a monopoly.

The Accidental Birth of Motor City

The sale provided the spark. Lawson used the patents from Simms to found The Daimler Motor Company in 1896. Simms stayed on as consulting engineer. His first job was to find a factory. Being a practical man, he found a fully equipped engineering works in Cheltenham called the Trusty Oil Engine Works. He recommended they buy it immediately because it had the tools and the skilled labour ready to go.

Lawson had other ideas. He and his associates bought a derelict four-storey cotton mill in Coventry instead. They chose it largely because one of Lawson's associates, a man named Ernest Terah Hooley, owned the building and wanted to offload it. Simms protested. He argued it was a mistake. He was overruled.

The British motor industry settled in Coventry largely because of a property deal that Simms opposed. Had Lawson listened to his engineer, history books might discuss the "Cheltenham Motor Industry." The automotive identity of Coventry rests on a foundation Simms tried to prevent.

The Godfather of Everything

Having kickstarted the manufacturing side, Simms turned his attention to organisation. The early motorists were a disparate bunch of eccentrics and tinkers who spent most of their time breaking down or being shouted at by policemen. Simms decided they needed a club.

In 1897, he founded the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland. It later became the Royal Automobile Club, or the RAC. It offered more than a place to have a brandy and complain about the speed limit. It was a serious lobbying organisation that fought for the rights of the motorist.

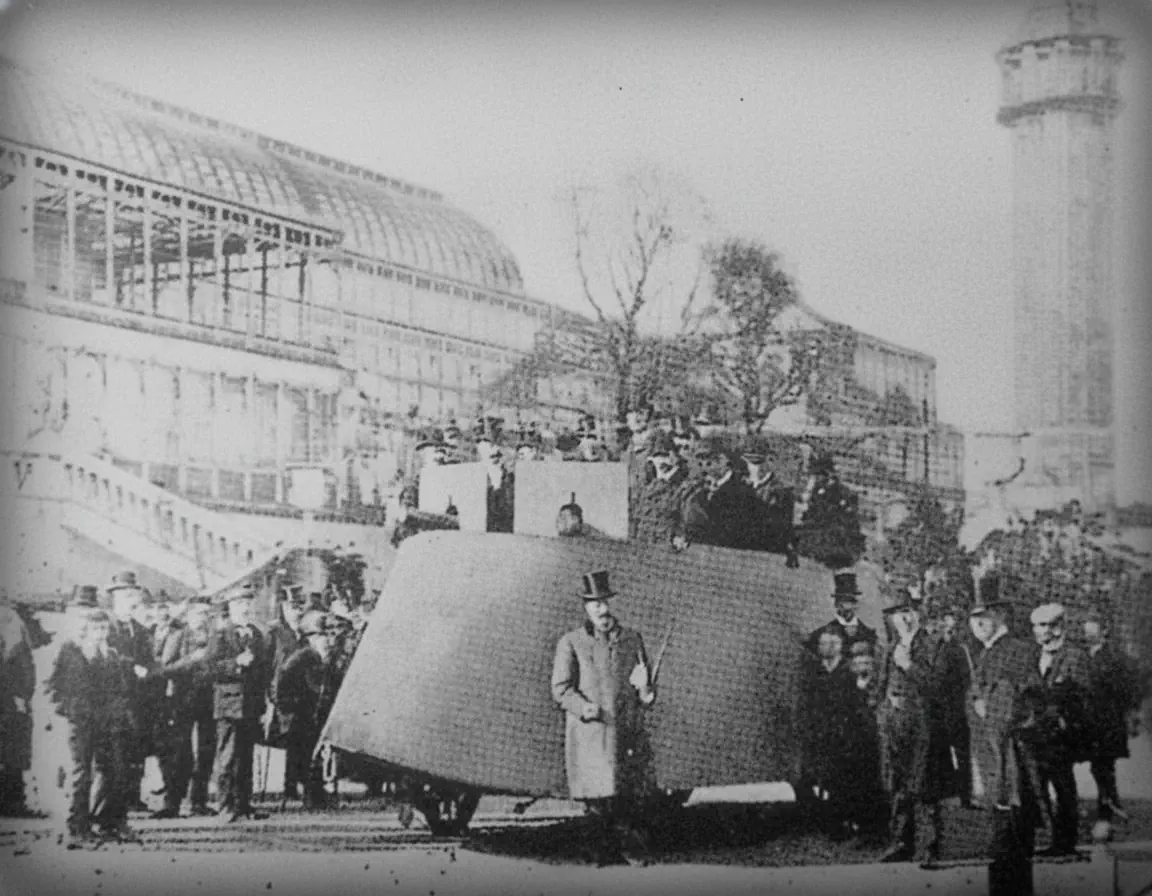

He did not stop there. He realised the industry was a mess of fragmented trade shows and shady deals. In 1902, he founded the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT). His goal was to bring order to the chaos. Under the SMMT’s banner, he organised the first official, industry-backed British Motor Show at Crystal Palace in 1903. Ten thousand visitors walked through the doors to see electric lights and rows of gleaming machines. It marked the moment the car stopped being a curiosity and became an industry.

The War Car and the Electric Skin

If Simms had a flaw, it was that his engineering imagination sometimes outpaced reality. Nowhere is this more evident than in his military inventions. Simms looked at the petrol engine and decided it needed a Maxim machine gun attached to it.

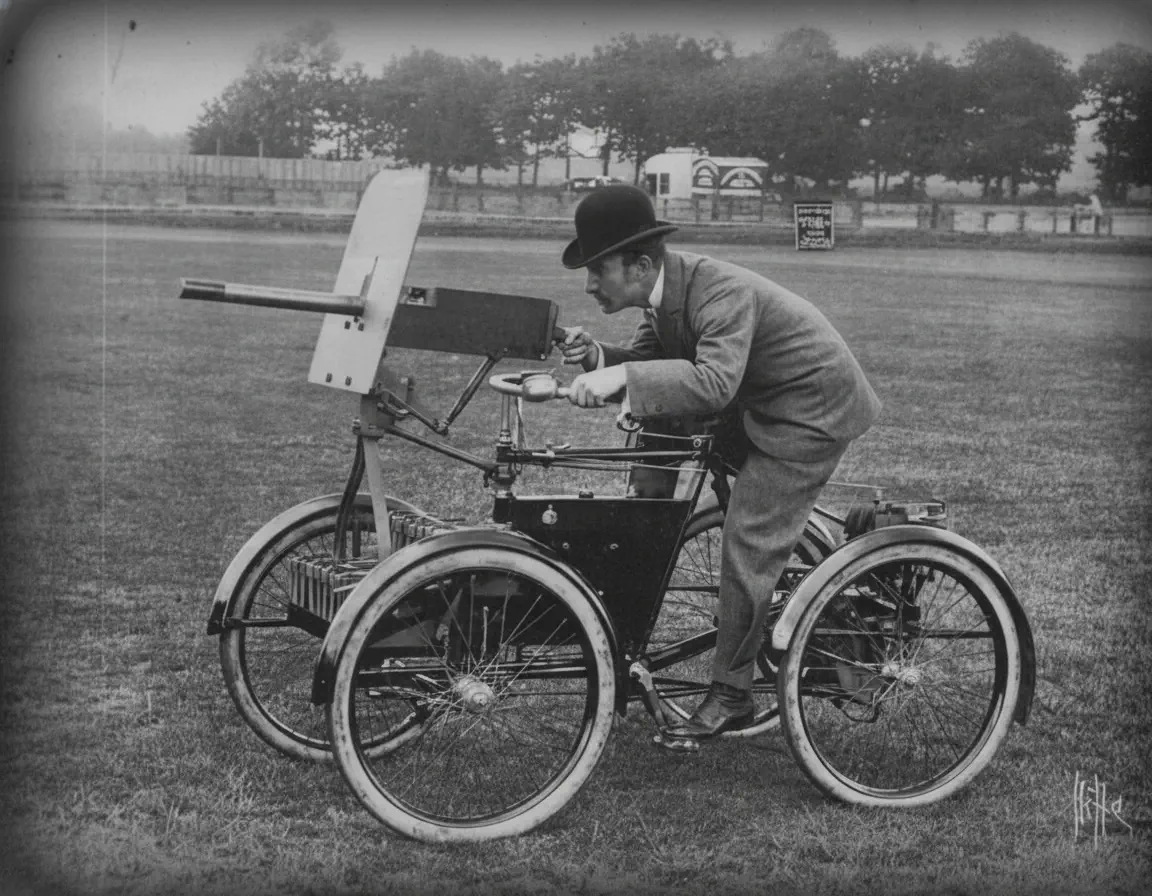

In 1898, he built the Motor Scout. It was a quadricycle with a machine gun mounted on the handlebars and a bulletproof shield. It looked terrifying. It resembled something a Bond villain would ride to the shops. He did not stop at quadricycles. In 1899, he designed the Motor War Car. Built by Vickers, this monster was 28 feet long. It was armoured with Vickers steel. It bristled with guns. It is widely considered the first purpose-built armoured car in history.

Simms added special features that bordered on science fiction. He proposed equipping the hull with an "electrified skin" to shock anyone who tried to climb aboard. He also designed pneumatic bumpers that acted as battering rams for "quelling mobs". The War Office looked at this electrified battering-ram tank-bus and decided it was too much. It never entered production. However, it proved that Simms was thinking about mobile armour long before the tank was actually invented.

A Messy Private Life

For a man so obsessed with order and structure in his professional life, the private life of Frederick Simms was a spectacular car crash. In 1903, while holidaying at his hunting lodge in Tyrol, he met a young Austrian woman named Lucie Greiff.

A whirlwind romance ensued. He brought her to London and married her in a high-society wedding in Mayfair. Then it all went wrong. Within months, the marriage had collapsed. Simms sent her back to Austria. When she returned to London to try and reconcile, she did not even know his home address.

The resulting divorce scandal delighted the Edwardian tabloids. Lucie hired private detectives to tail him. They eventually caught him in a "compromised" position at a hotel in Oxford Street. This was likely a standard setup for divorces of the time, where a husband would be discovered at a hotel to satisfy the legal requirements for ending a marriage. The newspapers contrasted the "dignified inventor" with his "pretty young wife in an enormous hat". It was the only time Simms ever really made the gossip columns. The public was far more interested in his domestic failures than his industrial successes.

The Man Who Named the Car

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of Frederick Simms is the language used today. Before him, people used clumsy phrases like "horseless carriage" or "petroleum spirit locomotive." Simms had an ear for a snappy brand name. He championed the words "petrol" and "motorcar" in the English language. He gave the world the vocabulary to talk about his invention.

Simms died in 1944 at the age of 80. He lived long enough to see his Motor War Car concept vindicated by the tanks of two World Wars. He saw the industry he birthed become the backbone of the British economy. Yet today, he is largely forgotten. He does not have a famous car named after him. His "Simms-Welbeck" cars are mere footnotes. He does not have a statue in Coventry. But every time an RAC badge appears on a grille, every time the doors open at a motor show, and every time someone uses the word "petrol," they are paying a small, silent tribute to Frederick Richard Simms. He was the man who brought the spark to Britain, even if he did accidentally start the fire in Coventry.